17.07.2025

Cold war economism

Members of TAS have fielded all sorts of arguments - some serious, most spurious. Mike Macnair cuts through the thicket to show why we need a minimum programme and a period of transition between capitalism and the highest phase of communism

This article responds to Peter Kennedy’s ‘Socialisms have prevented communism’ (Weekly Worker June 12 2025),1 though I also make limited reference to Nick Wrack’s June 11 posting on the Talking About Socialism site, ‘Communist unity - a change is needed’, so far as this reply to comrade Kennedy is made clearer by including reference to part of comrade Wrack’s arguments.2

Since a good deal of our debate has been about the continuing significance of the middle classes, I have delayed replying in order for us to publish Ben Lewis’s translation of Karl Kautsky on the ‘new middle class’ (June 26) and my own review of Dan Evans’ 2023 A nation of shopkeepers (July 3).3 I have also been delayed by academic responsibilities.

Comrade Wrack’s article amounted in effect to an ultimatum to the CPGB, that we had to stop putting our Draft programme forward and maintaining our defence of sharpness in polemic if the Forging Communist Unity talks were to continue. But “what is truth, said jesting Pilate, and would not stay for an answer”: TAS voted on June 23 to withdraw from the FCU talks, without waiting for an answer to the ultimatum. The article nonetheless contains substantive arguments in support of comrade Wrack’s views and against the CPGB’s views, arguments which are worth discussing. Comrade Kennedy’s article is a response to my May 29 piece, ‘Questions of communism’, which was, in turn, a critique of his April 22 post on TAS, ‘Differentiating socialism and communism’.4

The discussion has evolved, but it is necessary to remember where it comes from. As soon as the FCU talks began, it was clear that there were two major differences. One is the CPGB’s supposed ‘bad culture’, consisting of our defence and continued practice of the culture of sharp polemics on the left that prevailed down to the 1980s, outside those organisations which (like the Socialist Workers Party) had already become thoroughly bureaucratised. We have continued to defend this point elsewhere and it will only be marginal in this article.

The second was that for TAS comrades, as comrade Wrack puts it in his article, the CPGB’s Draft programme “is not fit for purpose” and it has to be abandoned at the outset if there is to be any unity. This led, in turn, to the question how the CPGB’s Draft programme “is not fit for purpose”.

The original claim was about length, and the inclusion of an introduction; comrade Wrack still complains about the introduction, though in the discussions CPGB comrades pointed out that any unified new organisation would need a new introduction (and on the question of length, that the Draft rules could be treated as separate from the Draft programme).

The point then became concretised as the rejection of the level of detail in the ‘Immediate demands’: that is, the minimum programme. This, in turn, led to the question of the CPGB’s arguments about why a minimum programme is needed and why its demands are consistent with the continued existence of markets and money. And this immediately posed the issue of the nature of the transition to communism.

Moral

Interlinked is the question of (as I have put it) “taking moral distance from Stalinism”. Comrade Wrack objects that “I do take a moral distance from Stalinism. Doesn’t Mike? Also a political, economic, democratic, human distance from Stalinism. Everything about Stalinism appalls me.” Agreed, but. The but is is, that what I mean by “taking moral distance from Stalinism” is forms of hand-waving away the actual defeat of the Russian Revolution: asserting that our socialism, or communism, will be different from Stalinism, without accounting for how Soviet power slid into Stalinism.5

‘State capitalism’ of the Menshevik variety (the Russian Revolution as premature and therefore a form of the bourgeois revolution) omits imperialism, and hence the tragic choices the Entente powers and the German Hindenburg-Ludendorff regime imposed on the Bolsheviks in 1917-18. Tony Cliff state capitalism (Stalinism as a higher stage of capitalism) turns Marx’s critique of political economy into nonsense. In both cases the mistaken choices of the organised workers’ movement go missing and Stalinism is merely a product of capitalism: moral distance is taken at the price of incomprehension.

‘All good under Lenin, all bad after his death’ and the critique of ‘Zinovievism’ is personality-cult politics and naturally supports a personality cult of Trotsky and, after him, of a succession of Trotskyist caudillos. Again, it makes disappear both the tragic choices of 1918 and the theorisation of these choices in 1919-21.

Comrade Kennedy’s argument makes Stalinism a part of a larger phenomenon, in which capitalism deploys socialism as a mode of defence against communism. But again this takes moral distance from Stalinism, as opposed to accounting for the tragic choices of 1918 and their false theorisation of 1919-21 - and as opposed to taking into account for future strategy the coercive deployment of Entente and German armed forces in 1918-21 and of what would now be called ‘economic sanctions’ in 1918-41 and 1946-91.

These arguments forget a very fundamental point made by Marx in 1852 in the Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte:

Bourgeois revolutions, like those of the 18th century, storm more swiftly from success to success, their dramatic effects outdo each other, men and things seem set in sparkling diamonds, ecstasy is the order of the day - but they are short-lived, soon they have reached their zenith, and a long Katzenjammer [hangover] takes hold of society before it learns to assimilate the results of its storm-and-stress period soberly. On the other hand, proletarian revolutions, like those of the 19th century, constantly criticise themselves, constantly interrupt themselves in their own course, return to the apparently accomplished, in order to begin anew; they deride with cruel thoroughness the half-measures, weaknesses and paltriness of their first attempts, seem to throw down their opponents only so the latter may draw new strength from the earth and rise before them again more gigantic than ever, recoil constantly from the indefinite colossalness of their own goals - until a situation is created which makes all turning back impossible, and the conditions themselves call out:

Hic Rhodus, hic salta! [Here is the rose, dance here!]6

I have made the point on more than one occasion before now that it is completely inconsistent with this idea, which expresses Marx’s scientific socialism, to cling to the texts of Marx, or those of the first four congresses of Comintern, as a dogma without regard to the actual defeat of the Russian Revolution or the various other experiences of failed leftist reform projects and failed revolutions.7 We do not have to have a common theory of Stalinism. But our theories of Stalinism have to yield strategic lessons that allow us to explain clearly why our revolutionary project will not produce the same failure.

Negative

I remarked in my April 3 report of an online FCU meeting on March 30 that

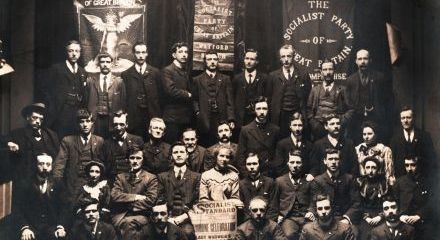

… there is some danger of a ‘negative dialectic’ in which we in the CPGB understate the radicalism of our Draft programme, while, on the other hand, the TAS comrades drive themselves, in opposition to it, towards the position of the Socialist Party of Great Britain that all that can be done is to make propaganda for socialism until there is a clear majority for immediate general collectivisation.

I think this danger has, in fact, materialised - but with understating the radicalism of the Draft programme appearing within the arguments of TAS comrades themselves.

I should make the point that SPGB comrades have pointed out that (whatever their past views) their current position is to support trade union struggles, and so on - but not to have specific minimum demands in a party programme or election manifesto.8 Comrade Wrack says:

My argument is that the working class should not seek to come to power prematurely, before it can implement its programme. By that, I mean its maximum programme.

It is not enough for it to come to power and implement only a minimum programme that is compatible with capitalism, and then leave capitalism more or less intact.

On the one hand, this is close to the SPGB comrades’ view. There should be no shame in that; and, conversely, saying that the comrades’ position is close to the SPGB’s is not a misrepresentation or smear. It is perfectly possible that the SPGB comrades are right and the various tendencies that came out of the Second International left and Comintern are all wrong. I have given reasons last month for thinking that the SPGB comrades are wrong, in the form of the point that the working class needs to take power because declining capitalism threatens human extinction or generalised warlordism, in spite of possible ‘prematurity’ from the point of view of the rise of the working class.9 TAS comrades, from comments on Peter Kennedy’s reply, disagree.10

On the other hand, the comrades claim that, because we oppose immediate nationalisation of the businesses of the petty-bourgeoisie, the CPGB - and I - want to defer communism into the distant future. This in spite of the fact that the Draft programme demands, among the immediate or minimum demands:

3.7 … We call for the nationalisation of the land, banks and financial services, along with basic infrastructure, such as public transport, electricity, gas and water supplies.

Faced with plans for closure, mass sackings and threats of capital flight communists demand:

- No redundancies. Nationalise threatened workplaces or industries under workers’ control.

- Compensation to former owners should be paid only in cases of proven need.

3.8 …

- A massive revival of council and other social house building programmes. The shortage of housing must be ended. …

- A publicly-owned building corporation to be established to ensure that planned targets for house-building are reached and to provide permanent employment and ongoing training for building workers.

3.9 …

- GPs, hospital doctors, consultants, etc who work in the NHS should be exclusively employed by the NHS.

- The pharmaceutical industry should be nationalised, so that the development of drugs serves human need, not the generation of profits.

3.13 …

- Open free, 24-hour crèches and kindergartens to facilitate full participation in social life outside the home. Open high-quality canteens with cheap prices. Establish laundry and house-cleaning services undertaken by local authorities and the state.

3.18 …

- Confiscate all Church of England property not directly related to acts of worship: eg, land holdings, share portfolios and art treasures.

- as well as extensive workers’ control measures in firms that are not yet nationalised; the active promotion of cooperatives; the abolition of limited liability; and so on. Would the implementation of this programme really “leave capitalism more or less intact”?

Paradoxically, the articles by comrades Kennedy and Wrack might in some ways have opened the way to narrowing the points of difference - if the TAS comrades had not voted to break off the talks. What follows will inevitably display a level of detailed engagement that may seem a bit labyrinthine. But this detailed engagement is necessary to clarity.

Kennedy

Peter Kennedy’s article responds to my ‘Questions of communism’ (May 29). This, in turn, responded to comrade Kennedy’s ‘Differentiating socialism and communism’ (April 22). To respond to the latest, it is thus necessary to summarise the route by which we arrived at the issues in it.

The starting point is that the CPGB Draft programme follows Lenin’s State and revolution (and others from the Marxist wing of the Second International, like Leon Trotsky in Results and prospects) in using the word ‘socialism’ to identify the regime that immediately succeeds capitalist class rule, and which in our view lasts for a significant period before passing into communism - meaning a classless and stateless society in which the means of production are held in common, and in which distribution is according to need. (My own individual view is that “working class rule” is better terminology for this transition period; but I agreed to accept the ‘socialism’ terminology in the programme as the basis for common action, given that the Draft programme does explain it in section 5.11)

TAS comrades have objected in the discussions, and comrade Wrack in his article objects, to this usage as either Stalinist (it is shared with Communist Party of Britain supporters, as the resident Stalinist of our letters column, Andrew Northall, has displayed in his own usage12) or as insistence on a “sect peculiarity” of the CPGB. The two objections are contradictory: if the language is ‘Stalinist’, it is using the language of the large majority of the world’s left, albeit to give it a different meaning. It is only a ‘sect peculiarity’ of the CPGB relative to the dogmas of Trotskyism about the meaning of the word.

In ‘Differentiating socialism and communism’ comrade Kennedy argued (as I have said above) that capitalism deploys socialism as a mode of defence against communism. In ‘Questions of communism’ I responded that comrade Kennedy’s approach had the strength of seeing the transition from capitalism to socialism as already in progress under capitalist rule. But this narrative failed as a historical narrative, because it was built on Cold War assumptions. In particular, I argued that it disabled understanding of what the debate about ‘socialism in one country’ and ‘national roads to socialism’ from the 1880s to the 1920s was actually about: that is, not about the development of full or ‘higher stage’ communism, but about the possibilities of the proletariat holding on to political power and carrying on immediate socialist construction in a single country.

In ‘Points of disagreement’, Comrade Kennedy responds to a series of individual points of mine. The first few paragraphs are addressed to my historical narrative of uses of ‘socialism’ and ‘communism’. He rejects my claim that Marx’s uses are inconsistent; though his only actual evidence for Marx’s consistency are The civil war in France, where ‘possible communism’ plainly means a mixed economy under working class political rule, and the Critique of the Gotha programme. I ran a quick search for ‘socialism’ in Marx on Marxists Internet Archive; I put in a footnote here a series of references where Marx’s usage of ‘socialism’ is not consistent with comrade Kennedy’s. Just to quote one substantive example:

… while the struggle of the different socialist leaders among themselves sets forth each of the so-called systems as a pretentious adherence to one of the transit points of the social revolution as against another - the proletariat rallies more and more around revolutionary socialism, around communism, for which the bourgeoisie has itself invented the name of Blanqui. This socialism is the declaration of the permanence of the revolution, the class dictatorship of the proletariat as the necessary transit point to the abolition of class distinctions generally, to the abolition of all the relations of production on which they rest, to the abolition of all the social relations that correspond to these relations of production, to the revolutionising of all the ideas that result from these social relations.13

Notice that my point is not a positive claim about Marx’s usage, but merely that Marx’s usage is - as I argued - inconsistent.14

More generally, comrade Kennedy simply fails to respond to my arguments: first, that using ‘socialism’ for what immediately succeeds capitalism is not just Lenin, but leftwingers in the Second International (I gave an example from Trotsky in 1907); and, second, that without recognising this common usage in the early 1900s left it is impossible to understand the SIOC debate.

Socialisation

In the second point, sub-headed ‘Socialisation’, comrade Kennedy’s arguments are fairly deeply obscure. It seems that, first, comrade Kennedy and I are in agreement that capitalism replaces household production with socially coordinated production.

Second, we are probably also in agreement that capital becomes a social power as such, which seeks to manage the economy as a whole; but in disagreement about when this happens. In comrade Kennedy’s view it is a symptom of capitalist decay, following Hilferding and Lenin (and, in his first article, Marx on the joint-stock company). In my view this phenomenon already happens when capital takes political power and, as a result, creates deficit financing of the state and government securities markets (late medieval city-states; Netherlands in the 80-years war, 1568-1648; Britain after 1688).

Third, comrade Kennedy’s argument for “containment” of the working class through socialism is in my opinion an over-generalisation of the political regime of the front-line states in the Cold War period, which never applied in the USA and ceased to apply after the fall of the USSR. Capital in decline does need the support of the labour bureaucracy. But it prefers for this purpose Lib-Labism (trade union support for a liberal political party) as in the case of the British Liberals in the late 19th century, the US Democrats today, or the Italian ex-communist Democratic Party.

He poses a series of points which, he argues, lead inexorably to the conclusion “that ‘socialisms’ have prevented communism; socialisms are inherent to the class struggle against the working class”.

First, “that capitalism has been ripe for worker revolution and transformation to communism for more than a century”. This claim was rejected by István Mészáros and has also been rejected by Moshé Machover, on the perfectly satisfactory ground that capitalism could only be said to have exhausted its possibilities for development when it became fully global - that is, from the 1990s.15 I have myself recognised the strength of this view, but argued that capitalism entered into decline at its core from the 1850s, while still expanding outwards, like a coral atoll or hollow tree, and that revolution was posed - by the destructiveness of capital - by the death agony of the British empire in 1914-48.16

Second, “that the period up to the mid-1930s was a period of capitalist stagnation”. This is straightforwardly untrue. The 1900s saw some recovery from the ‘long depression’ of the late 19th century. World War I produced stagnation in Europe, but the ‘Roaring Twenties’ in the USA.

Third, “that the period between the 1940-70s revived capitalist growth and that this period heavily involved Stalinism/social democracy (SU/SD).” The revival of growth in 1948-70 is certainly true. The reason is that the final overthrow of British world hegemony and the massive debt defaults of the war and immediate post-war years, sharply reducing capital values, enabled a major rise in the rate of profit relative to capital values, which supported extensive capital investments. Meanwhile, the US state’s policy of ‘containment’ of communism meant that the USA actively supported rightwing social democracy in western Europe with financial subventions and publicity operations, including academic interventions in the left.

Fourth, “that the period post-80s to the present (post-SU and SD) has been characterised by capitalist stagnation and financial parasitism”. This is over-simplified. The long boom ran out of steam around 1970. The USA broke with Bretton Woods in 1971, and began almost immediately to promote bank lending and ‘open economies’ in the ‘third world’ and in the Soviet satellite regimes. The Carter administration (1976-80) withdrew the support for rightwing social democrats, reallocating it to ‘human rights’ agitators and neoliberals. While the result from the 1980s on has been deindustrialisation in the core imperialist countries, in the ex-Soviet countries, and in Latin America and the Middle East, on the one hand financialisation has allowed very substantial profitability in the USA, and on the other there has been extensive industrial growth in China and south-east and south Asia.

Thus, the logic demanding the claim “that ‘socialisms’ have prevented communism; socialisms are inherent to the class struggle against the working class” simply fails: the premisses are too over-generalised from the specific features of the cold war period.

I can add that comrade Kennedy’s argument about the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) is also a mere repetition of cold war narratives. It clung to these, even while attempting to ‘soften’ the point. I say again: these Cold War narratives about the history of the SPD were actively promoted by authors coming out of MI6 and the OSS-CIA in the early cold war period - Carl Schorske, Peter Nettl, and so on. Their purpose was to show that the only ‘real’ options were ‘romantic but wrong’ Luxemburgism or ‘repulsive but right’ Fabianism - because both options were and are safe for continued capitalist rule.

The underlying assumption of comrade Kennedy’s arguments is that the spontaneous movement of the working class is naturally revolutionary, but only held back by ‘socialisms’. There is warrant for this in the more optimistic side of Marx’s writings: I have quoted above his 1850 claim that “the proletariat rallies more and more around revolutionary socialism, around communism”. This turned out to be over-optimistic, and hence Marx’s 1852 observations about proletarian revolution in The Eighteenth Brumaire, also quoted above.

The real ground for making the proletariat the centre of communist perspective is not this sort of over-optimistic romantic image of the proletariat, but rather that the proletariat is driven to create collective organisations - trade unions, cooperatives and so on, and collectivist political parties. This ‘warts and all’ ‘actual existing workers’ movement’ foreshadows the possibility of generalised cooperation as the alternative to capitalism.

State

Finally, we come to the question of the state. Comrade Kennedy says, in relation to the issue of ‘socialisation’, that, through the concentration of capital, “A point is reached where considerations about maximising profits (surplus value extraction) are joined by considerations about maintaining control over the working class. All of which necessarily embroils the state in effecting class containment and class compromise. Brushing this away as statist only confuses what is at stake.”

‘Statist’ here referenced my observation in ‘Questions of communism’ that “‘Socialism’ was not a synonym for communism in the Communist manifesto (1848). On the contrary, ‘socialism’ meant statist and nationalist political trends, variously characterised as feudal, petty bourgeois, German, conservative-bourgeois or critical-utopian.”

Why does characterising the ‘socialisms’ criticised in the Communist manifesto as ‘statist’ “confuse what is at stake”? It is not at all clear in comrade Kennedy’s article, but it seems that he interprets the role of the state in managing collective ruling-class concessions to the lower orders as resulting from the concentration and centralisation of capital reaching the stage of ‘monopoly’. Contrast Engels in The origin of the family, private property and the state, who sees it as foundational to the state as such (starting with Solon - died c560 BCE - in Athens).

Decline

I say above and elsewhere that we can see capitalism entering into decline at its core in 1850s Britain. And this decline can be seen, I think, in concessions to the middle classes in order to stave off the bloc between the working class and the lower middle class that was Chartism: in particular, the Limited Liability Act 1855, which blunts the incentive structure of capitalism, for the purpose of protecting the ‘savers and strivers’. But (as I said above), capitalism entering into decline at its core in the 1850s does not imply capitalism is “ripe for worker revolution and transformation to communism for more than a century”, which I guess is comrade Kennedy’s point. And the concessions are not primarily organised by ‘monopoly capitalists’ directly, but by and through the state.

At the end of his article comrade Kennedy reiterates the claim in ‘Differentiating’ that “the transition from capitalism to communism under the democratic rule of the working class, through communes and through the state, overthrows the capitalist state order”.

But what, in this context, are “communes”? Remember that the Paris Commune was the Paris local government under the French Third Empire, which the workers, starting with its (legal) militia, took over and transformed for its own purposes. Or is this another name for workers’ councils (soviets)? (It seems so from comrade Kennedy’s responses to Barry Biddulph in the comments on ‘Differentiating’.)

And what is “the state” that the working class is to use to overthrow “the capitalist state order”? What, for that matter, is “the capitalist state order” that is to be overthrown?

Back to Lenin’s State and revolution. TAS comrades argue that Lenin went wrong by using ‘socialism’ to mean what Marx called the first phase of communism, in which bürgerlicher Recht (bourgeois right/bourgeois law), meaning payment according to work contributed, persists. But presumably they do not reject Lenin’s general characterisation of the state (following Engels) as “special bodies of armed men having prisons, etc, at their command”.17

OK. So what is the “capitalist state order” here and what is the “state”, through which the working class acts? Again, we are left to guess. In the comments on ‘Differentiating’ comrade Kennedy writes that “the state ruling apparatus (military, criminal justice system, etc) will be quickly abolished and replaced by a workers’ militia and system of justice. Most other aspects of the state will be depoliticised and become the administrat[iv]e institutions of the commune from which real power is exercised.”

So the Sir Humphreys, or the various lower-down managerial hierarchies of public bodies, are to be “depoliticised and become … administrat[iv]e institutions”? The Bolsheviks thought they could do this, but found that the politics of the administrative bureaucracy was a tougher problem18 - as they could have deduced from Marx’s 1843 Critique of Hegel’s philosophy of right [law], where he points out that the bureaucrats pursue their individual interests, if this text had been available to them.19

I wrote against this policy at length in 2004 and 2007. I do not propose to repeat the arguments there; comrades can look them up if they want to (whether to explore them or to oppose them).20 I think that the extreme unclarity of comrade Kennedy’s arguments on the question of the state illustrates precisely why my arguments then were sound; and why we do need to fight now for democratic-republican constitutional principles as giving the necessary form of the dictatorship of the proletariat.

-

weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/1542/socialisms-have-prevented-communism. The text at talkingaboutsocialism.org/a-reply-to-mike-macnairs-questions-of-communism (June 2) is slightly different, since the Weekly Worker version is edited according to our style guidelines. The TAS text also has extensive comments.↩︎

-

talkingaboutsocialism.org/communist-unity-a-change-is-needed.↩︎

-

weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/1544/completely-different-foundations; weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/1545/rising-middle-classes.↩︎

-

weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/1540/questions-of-communism; talkingaboutsocialism.org/differentiating-socialism-and-communism.↩︎

-

Consider also comrade Lawrence Parker’s different argument about this: communistpartyofgreatbritainhistory.wordpress.com/2025/05/07/taking-distance-from-stalinism.↩︎

-

www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1852/18th-brumaire/ch01.htm. MIA has a long note on the Latin tag: www.marxists.org/glossary/terms/h/i.htm #hic-rhodus.↩︎

-

Eg, ‘Defeat was fault of enemy machine guns’ Weekly Worker May 24 2007 (weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/674/defeat-was-fault-of-enemy-machine-guns); and ‘Analysis of historical causes’, October 3 2024 (weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/1509/analysis-of-historical-causes).↩︎

-

Adam Buick on Cosmonaut in 2021: cosmonautmag.com/2021/06/letter-for-a-maximum-program; Robin Cox at weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/1535/letters (April 24 2025); Adam Buick at weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/1544/letters (June 26 2025).↩︎

-

In particular Nick Wrack and Barry Biddulph.↩︎

-

communistparty.co.uk/draft-programme/5-transition-to-communism. I argued the point against the idea that Marx’s hypothetical ‘first phase of communism’ in the Critique of the Gotha programme should guide us in ‘Socialism will not require industrialisation’ Weekly Worker May 14 2015 (weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/1058/socialism-will-not-require-industrialistion).↩︎

-

Eg, his letter Weekly Worker June 12 2025 (weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/1542/letters).↩︎

-

The class struggles in France chapter 3: www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1850/class-struggles-france/ch03.htm.↩︎

-

www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1844/08/07.htm; www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1844/epm/3rd.htm; www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1845/holy-family/english-materialism.htm; www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1845/holy-family/ch06_3_d.htm; www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1877/letters/77_10_19.htm; www.marxists.org/archive/marx/bio/media/marx/79_01_05.htm; www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1880/letters/80_11_05.htm; www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1881/letters/81_06_20.htm.↩︎

-

I Mészáros Beyond capital New York NY 1995; M Machover: matzpen.org/english/1999-12-10/the-20th-century-in-retrospect-moshe-machover.↩︎

-

‘Imperialism versus internationalism’ Weekly Worker August 11 2004 (weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/541/imperialism-versus-internationalism); ‘Leading workers by the nose’, September 12

2007 (web.archive.org/web/20081201225732/www.cpgb.org.uk/worker/688/macnair.htm).↩︎

-

www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1917/staterev/ch01.htm#s2.↩︎

-

L Douds Inside Lenin’s government London 2018.↩︎

-

www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1843/critique-hpr/ch03.htm (first published 1927).↩︎

-

‘Control the bureaucrats’ Weekly Worker November 11 2004 (weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/552/control-the-bureaucrats); ‘“Transitional” to what?’ August 1 2007; ‘What is workers’ power?’ August 8; ‘For a minimum programme!’ August 30; ‘Spontaneity and Marxist theory’ September 5; ‘Leading workers by the nose’ September 12. All the above are conveniently linked at communistuniversity.uk/mike-macnair-programme-and-party-articles.↩︎