05.06.2025

Capitalism as a star fort

The system might be in decline, but it has a whole complex of defence works available to it. Mike Macnair completes his three-part series on the transition from capitalism to communism

In the first article in this series, two weeks ago,1 I identified its immediate context - our discussions in the Forging Communist Unity process about the nature and duration of the transition to socialism - and I identified the fear that the CPGB is proposing a version of the ideas of ‘official communism’ as a part of the arguments. I discussed the 1950s Trotskyist debate round the same theme, and went on to criticise arguments about the topic of transition upheld by the Communist Party of Britain in its Communist Review.

These, I argued, illustrate the fundamental differences between the CPGB’s views of the transition period and those of ‘official communism’: we in the CPGB fight for radical democracy, while ‘official communists’ cling to bureaucratic-managerialist ideas; we reject ‘socialism in one country’, ‘national roads to socialism’, and alliances with (actually tail-ending) either the ‘democratic bourgeoisie’ (liberals) or the ‘national bourgeoisie’ (‘nationalists’) - all defended by ‘official communists’.

My second article, last week, explored the arguments of Peter Kennedy’s article about the issue on the Talking about Socialism website.2 A substantial part of that article returned, unavoidably, to the issue of ‘socialism in one country’ (SIOC). This was partly because the changes in the usage of ‘socialism’ and ‘communism’ in the left that are the context of comrade Kennedy’s argument partly grew out of arguments round SIOC. It was partly because the argument for rapid socialisation on the basis of the present relative marginality of small-scale production in the UK actually de facto presupposes either a SIOC approach (by excluding consideration of the involvement of countries with larger peasant and artisan countries) or a Socialist Party of Great Britain-style ‘impossibilist’ approach, in which it is necessary to wait for capitalist development to marginalise small production, thereby creating the conditions for mass adherence to communism.

In this third article I attempt to sketch my own view on this question. It is consistent with the CPGB’s draft programme and offers a defence of it against the arguments of TAS comrades; but other comrades should not be expected to take political responsibility for my arguments.

My framing assumption is that it is possible to draw lessons about the transition from capitalism to socialism from the transition from feudalism to capitalism. (I have argued elsewhere that lessons can also be drawn from the transition from the slaveholder urbanism of classical antiquity to feudalism; but I leave that aside for now.3)

Comrade Ed Potts argued at our March 8 Forging Communist Unity meeting that drawing such lessons is unacceptable, because proletarian revolution is different in nature from bourgeois revolution, being the transfer of power from minority to majority, rather than from one minority to another (assuming my note is right). I cannot remember if I made the point in that meeting that Leon Trotsky, in The revolution betrayed, said that “The axiomatic assertions of the Soviet literature, to the effect that the laws of bourgeois revolutions are ‘inapplicable’ to a proletarian revolution, have no scientific content whatever.”4

Analogously to comrade Potts’ point, Chris Cutrone in a letter to the Weekly Worker (February 12 2015) cited an 1899 extempore speech of Rosa Luxemburg (as quoted by the US cold warrior ‘socialist’, Michael Harrington) for the idea that

to chatter about the economic might of the proletariat is to ignore the great difference between our class struggle and all those that went before. The assertion that the proletariat, in contrast to all previous class struggles, pursues its battles not in order to establish class domination, but to abolish all class domination. It is not a mere phrase … It is an illusion, then, to think that the proletariat can create economic power within capitalist society. It can only create political power and then transform (aufheben) capitalist property.5

I responded that Luxemburg’s argument is:

… flatly contrary to Marx’s actual policy in relation to trade unions, cooperatives and the struggle for a workers’ political party within capitalism, which are abundantly documented from both the young and the old Marx. It is, in fact, a version of Ferdinand Lassalle’s ‘iron law of wages’ argument against trade unions …

In her 1900 book Reform or revolution, Luxemburg is a lot more careful in her expressions than in the 1899 speech to avoid suggesting that the proletariat cannot improve its economic situation in capitalist society; rather, there she correctly points out the limits of such improvements and that they will not gradually ‘grow over’ into socialism.

It is, in other words, perfectly possible for the proletariat to build powerful organisations under capitalism and to win real improvements in its conditions of existence, both through merely constructing these organisations and solidarity (cooperatives and mutuals), and through economic and political struggles. But, as long as the state order remains capitalist, these gains remain vulnerable to capitalist counteroffensives through the states (as we have seen since the 1980s); and, as long as the fundamental economic order remains capitalist, they remain vulnerable to the general destructive effects of cyclical crises, depressions and wars.6

The point is analogous to that of comrade Potts, because Luxemburg too, like the “Soviet literature” whose arguments are rejected by Trotsky, argues that inferences from the bourgeois revolutions to the proletarian are inadmissible.

In my opinion Trotsky is right. The primary ground for this view is that the idea of a contradictory interpenetration of capitalism and communism - both now, under capitalism, and after the capitalist political regime is overthrown - has in my opinion more explanatory power both in relation to the present and in relation to the failures of Stalinism, aka ‘bureaucratic socialism’, than the idea that the proletariat cannot make gains under capitalism, the idea of Stalinism as a stable exploitative regime, and the idea of a leap into Marx’s ‘first phase of communism’ as the remedy for this. More on this below.

There is, however, also a theoretical ground for the view that Trotsky is right. This is that the endeavour to construct a ‘Marxism’ without historical materialism fails. In fact the attempt to create a pure dialectical unfolding of the internal logic of commodity production already fails in the second half of volume I of Capital, which gives a historical narrative of the creation of the proletariat as a class and of the class struggles over the length of the working day.7 It is, in fact, historical materialism that offers real grounds in believing in the decline of capitalism and for hope in a socialist future, not any form of ‘Marxism’ purified from the supposed vices of ‘Engelsism’ or ‘historicism’.8

And, once we accept historical materialism, then we have to see the transition from capitalism to communism as a historical process like the transition from feudalism to capitalism (as Trotsky argued) - in spite of the fact that the potential proletarian revolution is a revolution of the majority, and that it involves conscious choices.

Apogee capitalism

In the CPGB Draft programme we assert: “The present epoch is characterised by the revolutionary transition from capitalism to communism. The main contradiction is between a malfunctioning capitalism and an overdue communism.”9 The point is analogous to Trotsky’s in the 1938 Transitional programme: “All talk to the effect that historical conditions have not yet ‘ripened’ for socialism is the product of ignorance or conscious deception. The objective prerequisites for the proletarian revolution have not only ‘ripened’: they have begun to get somewhat rotten.”10

Both of these formulas assume that the process of transition from capitalism to communism has begun under capitalist rule, as in declining capitalism both proletarianisation and proletarian organisations rise, and capitalism’s own distorted precursors to socialism also rise.

Social orders rise and decline: the period of their rise interpenetrated with the prior social order they are in process of negating; and the period of their decline interpenetrated with the new social order that is in process of negating them. Thus Friedrich Engels to Conrad Schmidt in 1895:

Did feudalism ever correspond to its concept? Founded in the kingdom of the West Franks, further developed in Normandy by the Norwegian conquerors, its formation continued by the French Norsemen in England and southern Italy, it came nearest to its concept - in Jerusalem, in the kingdom of a day, which in the Assises de Jerusalem left behind it the most classic expression of the feudal order. Was this order therefore a fiction because it only achieved a short-lived existence in full classical form in Palestine, and even that mostly only on paper?11

Apogee capitalism, by analogy with the kingdom of Jerusalem in feudalism, should be identified roughly with mid-19th century Britain or the late 19th century USA. It was characterised by the dominance of the cycle M‑C‑P‑Cʹ‑Mʹ:

M = money, C = input commodity, P = production by organised groups of workers under the dominance of the machine (whether a wind or water, steam or electrical machine), Cʹ = worked-up output commodity, Mʹ = realised money prices of Cʹ.

This cycle not only yielded the dynamic of the society: it also organised agriculture, infrastructure, and so on, with subsidies in the form mainly of stealing from pre-capitalist possessors. The limited liability company was only made available in the UK in 1855, in the USA at dates varying by state - and actual common use was later.12 Banks, railways, etc, could and did go bankrupt. Trade unions remained illegal; a considerable part of repression was either by capitalist militias (‘yeomanry’ in Britain) or private firms (‘Pinkerton men’, etc in the USA).

At this ‘apogee’ period there were property qualifications to vote in Britain and poll taxes, requiring payment for the right to vote, in the USA; women did not have the right to vote in Britain, and in the US (as of 1900) only in three western states and three territories.

Both employment and small business were precarious enough, and welfare systems sufficiently niggardly, with a hostile environment, to drive large-scale emigration - from Britain to the USA and to the colonies; from the previously settled parts of the USA westwards. (These last characteristics seem to be also present in China today, leading to 10 million emigrants compared with one million immigrants.13)

I describe apogee capitalism in very rough outline here for two reasons. The first is just to make the point that capitalism at apogee does not organise everything. Small-scale family production, state production, and production by charitable and other institutions continued to exist. The capitalist cycle was dominant, not total or pure. (This was, incidentally, Engels’s main point in his letter to Schmidt.)

Decline

The second reason is to flag how much has changed. It has changed partly by way of concessions to the working class: eg, the expansion of the suffrage, and the legalisation of trade unions.

It has changed partly by way of concessions to the middle classes, in order to preserve their support for capitalist rule against the working class: chiefly limited liability, but also a wide range of other concessions and subsidies. A notable feature in the imperialist countries is the radical expansion since World War II of managerial and supervisory roles relative to productive ‘grunts’: “The working class can kiss my arse. I’ve got a foreman’s job at last.”

It has changed partly by way of state intervention resulting from failures of pure-capitalist management, especially failures to deliver military effectiveness: the expansion of welfare and health services in response to the unhealthiness of military recruits, of state education in response to skills shortages, the statisation or regulation of infrastructure, subsidies to agriculture, subsidies to road transport because of its military role, and so on.

All these developments point in a single direction. Capitalism is tending towards communism: that is, towards a society in which the major means of production14 are held in common and production is consciously coordinated through collective decision-making, in which all can participate.15

The forms of statisation and subsidy point towards conscious coordination (in a deformed way); the concessions to the working class in the suffrage and the legalisation of trade unions point towards democratic collective decision-making, but are countered by forms of statisation (reduction of the powers of elected bodies, as the suffrage expands; judicial and other interventions to force managerialism in workers’ organisations; and so on).

Capitalism’s decline is like a coral atoll or a hollow tree: the centre is dying back, as the periphery has continued, down to very recent times, to expand. But this is not wholly true. As I said last week, increased proletarianisation in east and south Asia has been accompanied by deindustrialisation and de-proletarianisation in Latin America and the Middle East.

And the features of decline of capitalism mentioned above have the result that the USA, as it has entered into relative decline as a world hegemon power (like Britain in the 1850s), is not able to take territory and turn it into space for investment, as Britain (and other European colonial powers) did in the later 1800s. Instead, the USA inflicts mere destruction on countries that have in some way ‘dissed’ it: intensely visible in the results of US occupations in Afghanistan and Iraq and intervention in Libya, this effect already began with US responses to its defeat in Vietnam in 1975.

These forms of capitalist decline illustrate two underlying dynamics of the decline of a social order. The concessions to the working class, and to the middle classes, reflect the rise of the proletariat as a class and the need for the capitalist class and its state to control this rise. The movements into statisation and subsidies reflect the decay of the ability of the social dynamic of capital to organise social production. The forces of production grow beyond levels that capitalism, as a social order, can control; and tend, as a result, to turn into forces of destruction.

That the forces of production tend to turn into forces of destruction was already apparent in the need for two world wars (of which the second was vastly worse than the first) to get rid of the decline into parasitism of British world dominance and open the way to a new period of capitalist development under US world dominance in around 1950-1970. It is absolutely transparent in the USA’s merely destructive responses to its own relative decline.

Faster

Regrettably, the tendency to capitalist decline in the form of loss of control of the forces of production is, at present, moving faster than the tendency in the form of the rise of the proletariat as the class capable of reorganising society and leading the transition to communism.

The 21st century has seen a deepening tendency towards nationalism and irrationalism, and towards larger and more dangerous wars. The USA is actually fighting the Russian Federation through Ukraine as a proxy (wholly dependent on US arms supplies), and is contemplating pre-emptive war against the People’s Republic of China in the short term.

The Trump administration has reopened the idea of open colonialist annexations (of the Panama Canal, of Greenland and of Canada) and has actively promoted the readmission of the political descendants of Nazism, fascism, the US confederacy and ultramontanist Catholic tyranny to political respectability. Meanwhile, in Palestine the USA has moved from pretending to offer Arab reservations, like US Indian reservations, under the name of ‘two states’, to the open acceptance of the genocidal policy of the Israeli state, analogous to the 1831-1850 Trail of Tears, to the Herero genocide of 1904-07 and the Armenian genocide of 1915-16; again a policy that was supposed to be ruled out after 1945.

In this situation the most probable outcome of the 21st century is that the more and more overt US wars of aggression will lead to human extinction through generalised nuclear exchange. The second most probable is that no-one has the nerve to drop the bomb on the USA, and the result is generalised ‘Somalification’ - US-imposed state failure and reduction to warlordism, successively on Russia, then on China, then on continental Europe … There is a small hope of a way out: that is, a global alternative driven by an internationalist, proletarian communist movement.

Because capitalist decline producing disorder progresses faster than the rise of a proletarian movement as an alternative, a communist party needs a minimum programme for what it fights for under capitalist rule. And such a party would, if it won, inherit a world with very large petty-proprietor classes (as well as an enormous amount of reconstruction needed after capitalist destruction). Again the immediate abolition of money would not be posed, but movement in the direction of decommodification.

Outworks

Let us return for a moment to the transition from feudalism to capitalism. Apogee feudalism saw - not in the kingdom of Jerusalem, but in 12th-13th century Europe - the emergence of city communes, initially as forms through which the bourgeoisie, in its literal sense as the urban class, struggled for autonomy from feudal overlords. Outside Italy, strengthened monarchical states rapidly brought the city communes under control, promoting merchant oligarchs with grants of legal authority. The Dutch and English revolutions of the late 16th and 17th centuries involved the forcible overthrow of these merchant oligarchs as a necessary step to the overthrow of the monarchical state regimes (though, of course, once the capitalist class had power, new capitalist oligarchies returned).

In Italy, the weakness of the monarchical states allowed a number of communes to break through to actual sovereignty. With this came the beginnings of legal constitutionalism, state debt markets, and so on. Venice and Genoa acquired small colonial empires, creating plantation slavery on Mediterranean islands, and fought each other for hegemony. However, the dominance of surrounding feudalism and the limits of the new bourgeois constitutional orders meant that most of the communes were turned into signorie - lordships - which in turn became feudal duchies and so on. Even Genoa accepted subordination to the Spanish monarchy. This calamitous history was told and retold over and over again down to the 1680s, as proof that ‘there is no alternative’ to late-feudal monarchical absolutism. It only lost its purchase when the Dutch republic, and after 1688 English constitutionalism, showed that there was an alternative.

Meanwhile, the absolutist regimes artificially preserved peasant production and seigneurial controls on agriculture against the tendencies of the peasantry to differentiate through competition into capitalist farmers and wage-labourers and to break free of customary controls. And they created new artificial feudal relations, like Spanish encomiendas in the Americas or Louis XIV’s canal project set up as a feudal tenure, and noblesse de la robe (lawyers and civil servants made into aristos).

The situation of the 21st century workers’ movement is like that of the 15th-16th century bourgeois movement. The workers’ fighting organisations have been turned into outworks of the capitalist state, as the bourgeois communes were turned into outworks of the feudal-monarchical state. The latter ‘feudalised’ the communes by promoting merchant oligarchies under monarchical sponsorship. The capitalist states ‘business-ise’ the trade unions and the workers’ parties by promoting managerialism, and integration through the advertising-funded media and its delusive image of successful ‘media management’. This managerialism extends to the far left, and not only to its full-time officials, because the managerialist conception is internalised by many activists, including ‘independents’.

The second similarity is that the calamitous history of Stalinism plays the same role as the calamitous history of the signorie in attempting to prove that ‘there is no alternative’ to the capitalist order. The paradox here is that the part of the left that refuses to accept ‘there is no alternative’ in its very large majority clings to the essence of Stalinism - national roads to socialism, socialism in one country, and bureaucratic management in the form of bureaucratic controls on factions and on ‘unacceptable’ speech. This, too, extends today to the large majority of self-identified Trotskyists.

Late capitalist states, meanwhile, artificially create ‘private enterprises’ which are either large operations that cannot go bankrupt, like the privatised railways and water companies, or ultra-small businesses which are actually dependent on welfare subsidies (leaving aside ‘sham self-employment’).

Capital continues to rule, in spite of its manifest decline, because of the persisting strength of its state system; and because it does appear that ‘there is no alternative’.

I say “state system”, referencing Marx’s observation in the Critique of the Gotha programme that “the ‘framework of the present-day national state’ - for instance, the German empire - is itself in its turn economically ‘within the framework’ of the world market, politically ‘within the framework’ of the system of states”.

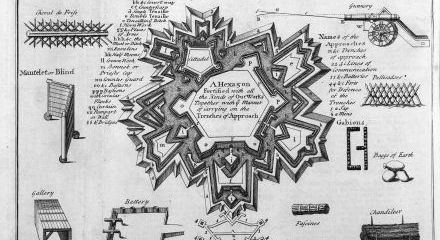

Walls and bastions

But I also refer to the state system as analogous to an early modern ‘star fort’. The heart of the regime - the curtain walls and bastions - is the loyalty of the armed forces of the USA. The next level out, the counterscarp and caponiers, is the loyalty of the weaker armed forces and police of the vassal states, like the UK. Beyond this, ravelins and hornworks are formed by the trade unions under managerialist control and by the large ‘centre-left’ parties linked to them.

Beyond this in turn are out-forts: the far-left groups under managerialist control by way of bureaucratic centralism, bans on ‘permanent factions’ and ‘parties within the party’, and other forms of bureaucratic and legalistic regulation of speech and communication between members. Left ‘independents’ who denounce the organised groups as ‘sects’, but cling to ‘anti-factionalism’ as a ground for unwillingness to actually organise, are part of the same system of managerialist loyalty to the capitalist state order. The attachment of the far left to the state system is visible in the efforts of authors active in MI6 and its US equivalent, the OSS, at the beginning of the cold war (Carl Schorske, Peter Nettl, and so on) to promote the claim that the only ‘real’ choices available to the workers’ movement are the coalitionist loyalism of Eduard Bernstein or the romantic but doomed mass-strikism of Rosa Luxemburg: both are safe options for capitalist rule.

I started this analogy with the loyalty of the armed forces core, and ended with the left independents as also loyal to managerialism through anti-factionalism. In this aspect, the problem of the state merges into the ‘there is no alternative’ problem. The bureaucratic centralism of the far left silences the possibility of posing a radical-democratic and internationalist alternative to the capitalist state, because it serves to reinforce both labour bureaucracy in general and the ‘lesson’ of Stalinism that socialism leads to tyranny, and thus ‘there is no alternative’.

Conversely, the merchant princes can be overthrown, as they were in the 1570s Netherlands and 1640s England. While far-left organisations are at present mostly bureaucratic-centralist out-forts of capitalist managerialism, this can be overthrown. That would open the way to a struggle for demanagerialisation of the larger workers’ movement - the capture of the hornworks and ravelins.

And this, in turn, if it succeeds, opens the way to the destruction of the loyalty of the core armed forces: the capture of the main walls. A nationalist or intersectionalist left has no chance of destroying or neutralising the loyalty of the US armed forces to the capitalist constitution. An internationalist and universalist left, in contrast, has the potential to do so: this was seen in the role of the anti-war movement in the US defeat in Vietnam, and on a larger scale in armed-forces radicalisation at the end of World War II, forcing the adoption of ‘containment’ rather than an immediate drive to reconquest; and still more clearly in British mutinies and related actions in 1919, allowing the survival of the early Soviet state.

Socialisation

The overthrow of the state order, by radical democracy creating a powerful and independent workers’ movement, leading in turn to undermining the loyalty of the armed forces and splitting them, is, as Marx put it in 1871, to “set free the elements of the new society with which old collapsing bourgeois society itself is pregnant”16

Back to the bourgeois revolutions. Until the feudal-absolutist state orders were overthrown, the states resisted capitalist development. Once they were overthrown, capitalist development was rapid, with the Netherlands transformed in its 17th century ‘Golden Age’, Britain in 1689-1720, France in 1789-1815. In the 21st century world, overthrowing the state system of the USA and its vassal states in favour of radically democratic, working class rule would similarly open the way to rapid socialisation, based on the distorted forms that have already taken place under capitalism.

The present problem of socialism/communism is that it is generally believed to have been tried and failed. The reasons for this belief are SIOC, which allowed the capitalists to strangle the Soviet economy by sanctions and in Comecon produced duplication of heavy industry complexes at the expense of effective planning; and bureaucratic managerialism, producing managers lying to keep their jobs, leading to ‘garbage in, garbage-out’ ‘planning’.

The solution to this problem is not proposals for more rapid and more general socialisation. It is not ‘extending democracy to the workplace’. It is proposals for radical democracy as an alternative to the mixed constitution/rule-of-law regime in the state, and to bureaucratic/managerialist regimes in the workers’ movement.

This sort of politics is at present the ideas of a small minority. But it has the potential to open the road to communism.

-

‘Centuries of Stalinism?’ Weekly Worker May 22: weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/1539/centuries-of-stalinism.↩︎

-

‘Questions of communism’ Weekly Worker May 29: weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/1540/questions-of-communism.↩︎

-

‘Historical blind alleys: Arian kingdoms, signorie, Stalinism’ Critique Vol 39 (2011), pp545-61 (pre-publication draft at www.researchgate.net/publication/271568956_Historical_Blind_Alleys_Arian_Kingdoms_Signorie_Stalinism).↩︎

-

‘Bernsteinian’: weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/1045/letters. I have cut the quotation for reasons of space.↩︎

-

‘Thinking the alternative’, April 9 2015: weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/1053/thinking-the-alternative (internal citation omitted).↩︎

-

I have argued this in more depth in ‘Law and state as holes in Marxist theory’ (2006) Critique Vol 34, pp211-36.↩︎

-

Besides ‘Thinking the alternative’ (see note 6), I have written about the issues repeatedly. See ‘Imperialism versus internationalism’ Weekly Worker August 11 2004 (weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/541/imperialism-versus-internationalism); ‘World politics, long waves and the decline of capitalism’, January 7 2010 (weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/799/world-politics-long-waves-and-the-decline-of-capit); ‘Marxism and theoretical overkill’, January 20 2011 (weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/849/marxism-and-theoretical-overkill); ‘Teleology, predictability and modes of production’, January 27 2011 (weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/850/teleology-predictability-and-modes-of-production); ‘The direction of historical development’, February 17 2011 (weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/853/the-direction-of-historical-development).↩︎

-

March 12 1895 (www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1895/letters/95_03_12.htm).↩︎

-

There is a useful study of the chronology by Ron Harris: ‘A new understanding of the history of limited liability: an invitation for theoretical reframing’ Journal of Institutional Economics Vol 16 (2020), pp643-64.↩︎

-

www.migrationpolicy.org/article/china-development-transformed-migration.↩︎

-

The “major” means of production because, for example, it is not necessary to communism that there should be no individual holding of knives, screwdrivers, paintbrushes, etc.↩︎

-

On “collective decision-making in which all can participate”, I formulate it in this way because of Engels’s claim that democracy is still a form of the state and the overcoming of the state is therefore also the overcoming of democracy. He made this in passing in his 1891 introduction to The civil war in France (www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1871/civil-war-france/postscript.htm#Ab) and in his 1894 preface to the pamphlet Internationales aus dem Volksstaat (1871-75) (MECW Vol 27, pp414-18, followed by Lenin in State and revolution (www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1917/staterev/ch04.htm#fw09). I am personally sceptical of this claim; in the 1891 introduction, which offers more (if still limited) argument for it than the 1894 preface, it is linked to the idea that the USA is a “democratic republic”. This accepts US ideological output and ignores the explicit elements of monarchy (presidency) and aristocracy (Supreme Court, Senate) in the US constitution. From the other end, the identification of Athenian democracy as a ‘state’ in Origin of the family is connected to the mis-diagnosis of Solon’s laws in the early 500s BCE as the invention of the state (MECW Vol 26, pp213 footnote), which reflects the generally foreshortened perspective of Origin, reflecting in turn lack of knowledge of the prior history of Mesopotamia and so on (mostly published after Engels was writing). But my formulation in the text avoids the issue.↩︎

-

www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1871/civil-war-france/ch05.htm (the whole paragraph is relevant).↩︎