21.03.2024

Delusions of ‘official optimism’

Socialist Appeal has discarded its ‘clause four’ Fabianism and made a ‘communist turn’, all explained by heady talk of a coming revolutionary crisis. Mike Macnair assesses its perspectives

The first thing to be said is: hats off to Socialist Appeal/The Communist for actually publishing their British perspectives document.1 The Morning Star’s Communist Party of Britain does publish its political resolutions,2 but for the Socialist Workers Party, the Socialist Party in England and Wales, the Alliance for Workers’ Liberty and Anti-Capitalist Resistance, perspectives documents remain private, with at most summaries being published.3

Keeping perspectives documents and their equivalents private is a fundamental political error. It is a foundational Marxist political principle that “the emancipation of the working classes must be conquered by the working classes themselves”.4 To apply this principle it is essential that real political choices, and the arguments to support one or another choice, be made available as far as possible to the working class, not restricted to some class of political specialists or ‘cadres’. Privacy of perspectives documents and debates thus negates the idea of working class self-emancipation.

There are, of course, material limits on this availability; but it should be noted that the Social Democratic Party of Germany before 1914 published the full stenographic minutes of its annual ParteiTage (conferences),5 and the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, with vastly smaller resources, also published stenographic minutes of its 1903 congress and endeavoured to publish as far as possible later party events.6 The material limits are massively reduced today by IT.

There are also ‘security’ limits caused by repression by the capitalist state and by the labour bureaucracy. We can agree that we should, for example, use pseudonyms where these can actually help avoid victimisation. But the widespread belief on the far left that keeping political differences and documents internal avoids state repression is merely ‘performative security’ or ‘security theatre’. The original 1944 RCP was thoroughly penetrated by state agents and bugs. The ‘Spycops’ inquiry exposed that the police had full knowledge of the supposedly secure proceedings of the SWP conferences.7 The “security theatre” of unpublished documents and ‘internal bulletins’ and so on merely keeps secrets from the broad workers’ movement - not from the state or the state’s agents and allies in the labour bureaucracy. So, once again, for The Communist to publish this document is decidedly positive.

Communist

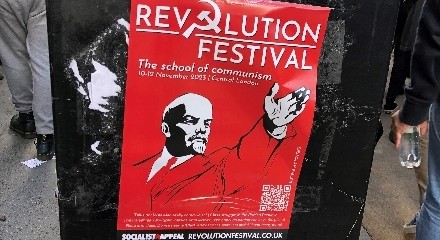

The second positive feature of the text is the general shift of Socialist Appeal to open self-identification as ‘communist’, of which this document is part. The Trotskyist and sub-Trotskyist far left has for too long imagined that calling themselves ‘socialist’ or whatever allows them to escape being identified as communists - it never worked. The effect was usually just to give an impression of dishonesty. This appearance of dishonesty would only be reduced where groups actually broke from communism, in the sense of rejecting the essential claims of opposition to imperialism and to their own country’s imperialist wars: but the usual consequence of this policy is, as with Schachtman, with the ex-Trot ‘neocons’ or with the ‘Eustonites’, to cease even to be leftists in any usable sense of that indeterminate term.

Socialist Appeal’s turn in this respect reflects another positive development: that is, that a (minority) section of the youth are keen to identify as ‘communist’, breaking the taboo around the word. On the basis of Socialist Appeal’s record the turn is likely to be its latest version of following political fashion, as I argued last November.8 But the underlying shift among the youth is positive.

The title of the document is ‘British perspectives 2024: theses on the coming British revolution’. The first part of this title, “British perspectives 2024”, is banal, but accurate. The second, “theses on the coming British revolution”, is inflated and plainly false. The document does not offer a set of theses. Nor is it an analysis of “the coming British revolution” conceptualised as a revolutionary process (analogous to the 1640s in England, or 1789 and after in France, or 1917 and after in Russia …). It offers a narrative or journalistic description of the recent evolution of the economic and political situation globally and in Britain, which concludes with the immediate tasks of the “Revolutionary Communist Party” about to be founded.

To explain the argument, it will be best to work backwards from its operational conclusions to the immediate supporting claims, and from there to the underlying assessment of global and British political dynamics. It will then be possible to assess the argument working forwards, from the global and British political dynamics, to the conclusions.

This will be a two-part discussion. This week I will lay out the argument and discuss the plausibility of its analysis of the global and British political dynamics. Next time I will look further at its claims about the existing left, about Socialist Appeal-RCP’s growth, and about the argument that a small organisation can under conditions of revolutionary crisis leap to becoming a mass party; and about what is unambiguously missing in the ‘Theses’: a programme for workers’ power and revolution.

Operative

The operative conclusion of the document is, essentially, that RCP members must get out there and recruit people. The immediate target is to move from (the claimed) 1,100 members now to 1,400 at the time of the May congress. Then, according to the document How communists are preparing for power in Britain (not published),

This congress resolves that every party member should recruit and consolidate at least one new member over the next 12 months. We agree on a target for Party membership of 2,000 by the 2025 congress. If we do our work properly, then this is a modest aim. The 2,000 must be used as a launch pad to 5,000 and then 10,000 members.

The justification of these targets is in the ‘Theses’:

We must set ourselves the goal of reaching 5,000 and then 10,000 members in a measurable short space of time. The objective situation demands it. This will allow us to build a base in every locality, workplace and trade union.

In the revolutionary storms that lie ahead, a small revolutionary party can emerge onto the scene and rapidly grow amongst the working class.

Such was the case with the Spanish POUM, a centrist organisation (ie, one that wavered between reformism and revolution), which grew from about 2,000 members to 40,000 or 50,000 in a matter of weeks in the heat of the Spanish revolution.

Trotsky’s April 1937 comments on the POUM (Workers’ Party of Marxist Unification, created in 1935 by unification of the Spanish Trotskyists with the ex-Communist Party ‘Right Opposition’) are (selectively) quoted in support of this view.9

As I argued last November, this line repeats the arguments of Gerry Healy and his co-thinkers for the launch of the Workers Revolutionary Party in November 1973 and of Tony Cliff and his co-thinkers for the launch of the Socialist Workers Party in January 1977. The argument was in my opinion already wrong in Trotsky’s hands in 1937, and in Healy’s and Cliff’s hands in the 1970s. But I will return to this point in my next article. Our present concern is that the justification of this approach has to be that the opportunity exists for the new RCP to grow explosively, because there is a “political vacuum” and Britain is “entering a pre-revolutionary period”, analogous to conditions in Russia in 1905 or 1917, or to Spain in 1935-37.

Vacuum

The “political vacuum” is a judgment, in the first place, about the Labour left, that

… the younger generation, who have known nothing but austerity and capitalist crisis, will be looking far beyond such [left-Keynesian] piecemeal ‘solutions’. The reformist politicians are increasingly exposed for what they are.

Figures like Jeremy Corbyn will not be a point of reference for this generation. Instead, the youth are completely open to radical, revolutionary and especially communist ideas.

While this is almost certainly true of the current Labour left - smashed and driven out in the wake of the failure of Corbynism - the ‘Theses’ are sufficiently cautious to include the statement: “We do not write off the reformist mass organisations, which can be transformed by events.” That means (if it means anything) that a new Labour left can be produced by the dynamic of events.

The Morning Star’s Communist Party of Britain will not benefit, say the ‘Theses’, because:

In such a period, in the past, the old so-called Communist Party would have grown substantially, given its name. But it is steeped in reformism and nationalism, and has been reduced to a shadow of its former self. It spreads illusions about the United Nations and offers pacifism instead of revolutionary politics. If people join, they quickly leave, given the party’s reformist politics.

No use is made of the CPB’s official membership figures returned to the Electoral Commission (usefully discussed by Lawrence Parker last August), which showed a sharp dip in the Corbyn years, followed by a rise in 2020-22, taking the party to nearly 1,200 members - a 54% increase on 2016, and 33% on their official figures of around 900 in the pre-Corbyn years.10

It is also noteworthy that on page 11 of The Communist (No4, March 14) Rob Sewell writes on ‘From opportunism to ultra-leftism: the criminal zig-zags of the Stalinists’ - a purported historical account of the old ‘official’ Communist Party, which assumes that the current CPB is the simple continuity of that party, rather than the largest of the fragments left when the Eurocommunists liquidated that party in 1991. As for the far left, “Most of the far-left sects have over the past period watered down their ideas in an attempt to find a shortcut to building a revolutionary organisation. This has completely failed.” Again, there is no actual attempt to analyse the state of the far-left groups. For example, the Socialist Workers Party as of December 2023 claims 6,000 ‘registered members’; the finance report for its annual conference states that 2,504 members pay subs to the party. They recruited 1,234 members in 2023, of whom 711 pay subs. They report growth in subs (which is a good indicator of actual membership) since 2020, and growth in sales of publications in 2023.11 On a smaller scale, RS21 claims to have grown from 115 at its launch in 2014 to over 400 in January 2024.12 Neither is a case of “completely failed”.

Crisis

The next level up from the ‘vacuum’ is the assessment that mainstream British politics is in crisis: “Britain has gone from being perhaps the most stable country in Europe just over 10 years ago, to possibly the most unstable today.” The Tory Party “has become a laughing stock” and electoral defeat will lead to a further shift of the Tories to the right. Hence:

The ruling class have no alternative but to rest upon the rightwing Labour leaders, who in turn are keen to do their bidding. The scene will be set for class battles and rising radicalisation, as Starmer continues where the Tories left off …

As a result, the trade unions will be pushed into opposition or semi-opposition to the Labour government, given the pressure from below.

This argument supposes that the trade union leaderships will be unable to hold back strike struggles for any significant period: unlike under the 1929-31, 1945-52, 1964-70, 1974-79 and 1997-2010 Labour governments.13 This is possibly true. But the argument depends on the supposition that the dynamics of the next Labour government will be more like those of the Popular Front governments in Spain and France in 1936 than like those of any British Labour government so far.

In favour of this view the ‘Theses’ proposes, as an immediate cause, the fact that British capitalism is in relative decline, shown by slow growth, “largely due to the failure of the capitalists to reinvest their profits into modernising industry”, leading to a “permanent slump” and median household incomes, and those of the poor, falling behind “peer countries” Canada, Australia, Germany or France.14 Taking this analysis (for the moment) for granted, British relative decline was already a matter of public concern in the early 1900s, and the diagnosis of failure to reinvest in modernising industry was already a theme of discussion under the Wilson governments of 1964-70 and 1974-79.

Other things apart, one would expect British relative decline (after the loss of the world hegemony in 1940) to be a gradual slide towards financialisation (as in 16th-17th century Genoa and Venice, and the 18th century Netherlands) followed by economic dominance of the tourist industry (as in 18th century Venice), until the hollowed-out state is finally knocked over by open war (Netherlands in 1795, Genoa in 1796, Venice in 1797). This evolution would tend to weaken the local working class, as it goes on. The expectation of revolutionary crisis in the ‘Theses’ has to come not from the specific British situation, but from the world situation.

And so it does. The ‘Theses’ begin with the claim that “Capitalism worldwide is in a state of terminal decline”. The case for this view is essentially journalistic observations about austerity as the price of the 2008-09 bailouts and the difficulties of any new bailout in the face of a new crash.

Chinese capitalism, which previously played a key role in helping to bail out the system, is now facing its own crisis. From a factor of stability, it has become one of instability, as the Chinese ruling class strategic interests collide with those of the USA.

The wars in Ukraine and Gaza are seen as forms of economic shocks, with the USA “facing another Afghanistan-style humiliation” in Ukraine; and political polarisation in the USA, with Trump in particular expressing that “the ruling class has lost or partially lost control of the situation”.

Plausible?

How plausible is this argument? The first and essential point to be made is that it is necessary to explain to the broad workers’ movement, as far as possible, a realistic assessment of political events and dynamics - not the ‘official optimism’ so common on the left. The point was well made by Trotsky in 1932, discussing the Soviet economy:

There is nothing so precarious as sympathies that are based on legends and fiction. There is no depending on people who require fabrications for their sympathies. The impending crisis of the Soviet economy will inevitably, and within the rather near future, dissolve the sugary legend and we have no reason to doubt will scatter many philistine friends into the bypaths of indifference, if not enmity.

What is much worse and much more serious is that the Soviet crisis will catch the European workers, and chiefly the communists, utterly unprepared, and leave them receptive to social democratic criticism, which is absolutely inimical to the Soviets and to socialism.

In this question, as in all others, the proletarian revolution requires the truth, and only the truth. … First and foremost we serve the Soviet republic, in that we tell the workers the truth about it and thereby teach them to lay the road for a better future.15

The point that to “tell the workers the truth” is a fundamental political principle was repeated by Trotsky on several occasions.16 In the end, it took longer for the crisis of the Soviet economy to manifest itself than Trotsky imagined. But, when it did materialise, the disastrous consequences of ‘official optimism’ were all that he had feared.

The argument of the ‘Theses’ is, in my opinion, an example of ‘official optimism’. It constructs its argument by selecting one-sidedly all the elements of the political dynamics which point towards a rapid leap forward of the revolutionaries, while excluding all those elements which tend either to slow down the process of development or to point in the direction of the victory of nationalist authoritarianism and war.

The practical effect of this one-sided ‘official optimism’ is - as in the SWP today, in the WRP in the 1970s, in the Maoist organisations of the same period worldwide and in the ‘official communist’ parties in their ‘leftist’ periods - necessary to keep the rank-and-file membership running around like blue-arsed flies without time to think or to question their leadership.

World

Is the world about to tip into open global crisis, of the sort of 1848-50 in Europe, 1859-1871 in Europe, the US and Japan, or 1914-1950 globally? It is certainly possible. It has to be said, for reasons I will discuss below, that if the left goes into such a crisis still thinking in the way Socialist Appeal/RCP, the SWP, and so on think, the outcome will be the same as the fate of the Chilean left in and after 1973, the Argentinian left in and after 1976, or the Iranian left in the revolutionary crisis of 1979-81: destruction.

That said, the case offered by the ‘Theses’ for this view is essentially impressionistic. We are told, in the first place, that “The strategists of capital are terrified of a new slump, as they have used up all their reserves in staving off a depression over the last 15 years.”

It is true that the response to the 2008-09 crash was massive bailouts, funded by public borrowing, and states leaning on lenders to keep ‘zombie borrowers’, both consumer and business, afloat. The background was that 2008 was a shock to the political regime, which for 10 years had been insisting on the “great moderation” (in defiance of the previous ‘East Asian’ and ‘dot-com’ crashes) and insisted that financial engineering, allowing the poor to borrow on mortgage, would resolve the problem of social inequality.

Since then, expectations have been radically lowered; the capitalist regimes have operated a state-controlled crash in the form of the pandemic lockdowns in 2020; and ‘reshoring’ and ‘near-shoring’ operations have reduced US vulnerability to trade interruptions, and the US has turned to open protectionism against China, ramping up anti-Chinese propaganda, as well as to war in Ukraine. Both turns also operate as US protectionist measures against France and Germany (as was also true of the 2003 invasion of Iraq).

As a result, a financial crash like 2008-09 would be manageable for the USA, even if it involved unwinding market positions and financial engineering operations on a large scale, with massive losses to creditor interests. For a single example, defaulting US debt to China under the name of ‘sanctions’ would free up $769 billion.17 This sort of option is just more ‘thinkable’ today than in 2008.

Is the USA, in fact, “facing another Afghanistan-style humiliation” in Ukraine? This claim is at least premature. Ukraine is currently experiencing a ‘shell crisis’ like 1915 in the UK.18 But the result has not been far-reaching Russian breakthroughs, but slight movement of the front lines. The war can go on with this character for several years (it should be remembered that it started in 2014 with the US-controlled ‘Euromaidan’ operation, the uprising of Russian-speakers in the Donbas and the Russian seizure of Crimea in that year). It remains a proxy war in spite of the presence of Nato special forces and missile specialists in Ukraine: not a full commitment of US and allied forces like Afghanistan, which, moreover, only ended in “humiliation” after 20 years. The war, meanwhile, has delivered a boom for arms manufacturers.19

What about US political polarisation and Trump? Certainly, US political dynamics are moving towards the reversal of the gains on the rights of black people, of women and of ‘LGBT+ people’, since the 1960s. The US is similarly moving towards radical increases in censorship, especially on campuses - spearheaded by Zionist Democrats as much as Republicans.

Trump is a maverick, and it may be that the ‘deep state’ will act against a second Trump presidency: but on March 20 he is reported to have announced a clear commitment to Nato, as long as the Europeans pay their way: that is, merely demanding increased European tribute, as presidents GHW Bush, Clinton, GW Bush and Obama all did before him.20 And in office, in spite of all the rhetoric, he delivered merely conventional Republican tax cuts for the rich and welfare cuts for the poor, and the appointment of extreme-rightist judges. It is far from clear that the actual dominant capitals in US politics will be seriously concerned about a second Trump presidency.

Capitalism as such is in decline. This decline was already reflected in the creation of limited liability in 1855. This blunts market incentives in order to secure consent for the political regime from small savers. Since then there have been on-off increases in state intervention to deal with any number of ‘market failures’, and much modern ‘privatisation’ is merely privatisation of profits, while leaving the state on the hook for losses.

The USA is also - and has been since around 1970 - in relative decline as an industrial producer, while remaining absolutely dominant in military power and finance - as the UK was from, roughly, the 1850s. China has emerged as a rival, but remains much weaker than the US - comparable to the relation of Germany to the UK in 1871-1914. Europe, which could develop as a real rival to the US, remains under tight US political control (like the British political control of Germany and the US before 1861 through ‘states’ rights’). This is reflected in the Ukraine war, which is absolutely against European interests, and the US’s ability to bring France and Germany ‘back into line’ on the Middle East, and crush the Corbyn movement in Britain, through the ‘anti-Semitism’ smear campaign.

Britain’s response to relative decline was the expansion of its territorial empire as a zone of protection (through ‘non-tariff barriers’). The US’s response has been, since the mid-1970s, the mere export of destruction through wars and proxy wars. This reflects the overall decline of capitalism: the UK had mainly a net emigration down to its loss of global hegemon status; the USA does not.21 It was the growth of capitalist industry, at the expense of peasant agriculture, which drove emigration; the US, rather, depends on continued immigration (as the UK also does) to get low-status jobs done.

Global collapse, therefore, does not look immediate. Rather, there is a drive towards larger and more destructive wars - which will continue, irrespective of who is US president. The UK is affected by this drive, but it is not about to precipitate a full-scale crisis.

Britain

The argument that Britain is unusually unstable is a surprising one in a Europe in which a ‘post-fascist’ party governs Italy, and extreme right parties have been growing dramatically in France, Germany, the Netherlands, Spain, Portugal …

As I said earlier, the argument in the ‘Theses’ for British relative decline due to underinvestment is an old argument, going back at least the 1960s (when comrades Alan Woods and Rob Sewell were young …). Since then, the Thatcher government promised to ‘Make Britain Great Again’ by abandoning the old industries, setting free financial innovation, and encouraging foreign direct investment in the remaining industries (cars, for example, where foreign-owned maquiladoras (assembly plants) superseded the old British industry; or the sale of ‘British champion’ International Computers Ltd to Fujitsu, which led to the Post Office scandal22). The Blair-Brown government continued this policy by promoting ‘public-private partnership’ arrangements and financial engineering in local government as an alternative to tax rises.

It is this Thatcher-Major-Blair-Brown regime of British ‘recovery’ which is now coming apart in the ‘crises’ in the National Health Service and in local government - both caused by financial engineering and public-private partnerships. The underlying failure of this regime to deliver on its promises is also reflected in the jails running out of space,23 in the problems of river pollution, in the housing problem, and in the squeeze on defence spending in spite of the ongoing calls from military figures to increase it.

Is the decay of this regime likely to lead to an actual revolutionary crisis in Britain in the short term? Once we see that there is a global turn away from the regime of neoliberalism, and in the direction of protectionism and great-power war, this actually becomes significantly less likely.

In the first place, the USA will be (already is) increasingly concerned that its vassal states deliver military support to its projects. If that involves unwinding some or all of the financial engineering of the neoliberal period through ‘financial repression’, that is a price US administrations are likely to be willing to pay.

Secondly, if the Tories are in total disarray (true), this is due to the radical inconsistency between the dreams of setting financial engineering further free through Brexit, and the supposed material benefits that would accrue from this project (as in Liz Truss’s dreams), plus the actual constraints of British dependency on a low-tax regime to attract hot money, and the global turn, also reflected in the Brexit vote, away from neoliberal globalism towards nationalism and traditionalism.

But, having crushed the Labour left, capital now has to hand a trustworthy ‘second eleven’ in the form of the Starmer-led Labour Party. Sir Keir has already abandoned most of Labour’s alternative policies - but remains 20 points ahead in the polls; and none of the Trotskyism of his youth, or his human rights lawyering before he became Director of Public Prosecutions, has been deployed against him by the press. The trade union leaderships in their large majority have backed him against the left.

It is true that a Starmer government will probably deliver nothing for the working class except a few crumbs. But the context of the war drive, and losing the Tories, means that Starmerite Labour in government will be able to explain continuing cuts and repression by the necessities of overcoming national difficulties and pursuing national defence.

Yes, we have a mass movement against the Gaza war. But not against the Ukraine war.

Yes, the working class will eventually be driven to resist through strike struggles, and so on: as it has been driven to resist on a limited scale by the inflation/‘cost of living crisis’ caused by the Covid crash and the Ukraine war. But that is in principle the same dynamic that emerged under previous Labour governments: not a failure of the political regime as such.

-

www.communist.red/theses-on-the-coming-british-revolution/.↩︎

-

57th Congress (2023): www.communistparty.org.uk/for-a-united-front-against-monopoly-capitalism-and-war; 56th Congress (2021): www.communistparty.org.uk/56th-congress.↩︎

-

SWP: socialistworker.co.uk/news/swp-conference-2024-palestine-the-movement-and-revolutionary-politics; SPEW: www.socialistparty.org.uk/articles/108418/01-03-2023/socialist-party-conference-fighting-for-permanent-victories-for-the-working-class; AWL: www.workersliberty.org/story/2024-02-19/awl-conference-2024 (notably illustrated with a photo of AWL placards demanding “Arm Ukraine” and “Russian troops out”); A-CR: anticapitalistresistance.org/challenging-capitalism-perspectives-from-anticapitalist-resistance.↩︎

-

www.marxists.org/history/international/iwma/documents/1864/rules.htm.↩︎

-

Online at library.fes.de/parteitage.↩︎

-

1903: Minutes of the Second Congress of the RSDLP, translated and annotated by B Pearce (London 1978); RC Elwood (ed) Resolutions and decisions of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union Vol 1: The RSDLP 1898-October 1917 Toronto 1974 (the original publication records referenced passim show the efforts to publish).↩︎

-

RCP: eg, www.marxists.org/history/etol/revhist/brittrot/ssreport.html, or G Kassimeris and O Price, ‘“A new and disturbing form of subversion”: Militant Tendency, MI5 and the threat of Trotskyism in Britain, 1937-1987’ Contemporary British History Vol 36 (2022), pp358-60; SWP: ‘Spycops and our response’ Weekly Worker May 19 2022: weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/1396/spycops-and-our-response.↩︎

-

‘A communist appeal to Socialist Appeal’ Weekly Worker November 9 2023: weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/1466/a-communist-appeal-to-socialist-appeal.↩︎

-

‘Is victory possible in Spain?’ April 23 1937, in The Spanish Revolution (1931-39) New York 1973, p263. When Trotsky wrote, the POUM was about to be destroyed in the ‘Barcelona May Days’ (May 3-8) and what followed by the Popular Front government’s armed forces and the Spanish Communist Party and NKVD.↩︎

-

commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Data:Communist_Party_of_Britain_membership.tab; Parker: communistpartyofgreatbritainhistory.wordpress.com/2023/08/09/communist-party-of-britain-membership.↩︎

-

SWP Pre-conference bulletin No3, p7 (registered members), pp45-48 (financial report).↩︎

-

The 1924 Labour government was too short-lived for the issue to arise.↩︎

-

The UK is ranked 18 out of 162 in the world on this measure: wisevoter.com/country-rankings/median-income-by-country/#united-kingdom.↩︎

-

‘The Soviet economy in danger’ (October 1932): www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/1932/10/sovecon.htm.↩︎

-

Eg, ‘Discussions on the transitional programme’, 1938: www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/1940/05/backwardness.htm.↩︎

-

www.statista.com/statistics/246420/major-foreign-holders-of-us-treasury-debt.↩︎

-

edition.cnn.com/2024/02/24/business/us-europe-defense-industry-spending/index.html.↩︎

-

‘Trump: US will 100% stay in Nato - if Europe plays fair’ The Times March 20.↩︎

-

www.gale.com/intl/essays/amy-j-lloyd-emigration-immigration-migration-nineteenth-century-britain.↩︎

-

‘Justice at a huge price’ Weekly Worker January 18: weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/1474/justice-at-a-huge-price.↩︎

-

‘Not tough on the causes’ Weekly Worker October 19 2023: weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/1463/not-tough-on-the-causes. This is back on the parliamentary agenda this week: see ‘Sunak faces another Tory revolt over jail sentences’ The Times March 20.↩︎