22.06.2023

A year of strikes

We must go beyond Labourism. Kevin Bean assesses the upsurge in trade union action and its limitations

June 21 marked one year since the first RMT strike, which ushered in the highest level of industrial action for more than three decades. With 3.7 million working days lost through strikes from June 2022 to April 2023, according to official statistics, this is the highest number for any 11-month period since July 1989 to May 1990, when 4.8 million days were lost.1

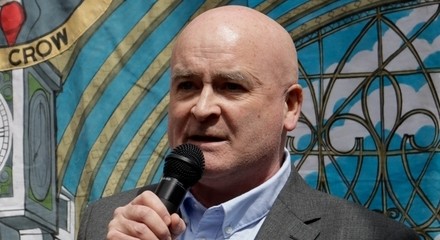

With disputes and strikes involving workers in sectors ranging from the post office and the civil service through to the health service, schools, local government, universities and transport, it seemed to many commentators - whether in the left or the bourgeois media - that ‘the militant working class was back’. Tory ministers reprised the Thatcherite playbook and declared that they would not give in to union leaders such as Mick Lynch ‘holding the country to ransom’, as they supposedly did in the 1970s. They even tried to use the Ukraine war, with Lynch and co being Putin agents. But nor did that work.

The year of strikes has drawn widely differing groups of workers into action, some for the first time, such as the Royal College of Nursing. Although the disputes have different proximate causes and demands, the common element is the defence of wage levels and working conditions.

We should also not discount the way that employers have attempted to use the historical weakness of the organised working class to further undermine conditions and benefits, such as pensions and permanent contracts. The long-running pensions dispute in the universities and the attempts by the railway employers to worsen the conditions of drivers and other workers are examples of disputes which are just as much about a wider defence of jobs and conditions as attempts to ensure that wages keep pace with inflation.

Back to 1970s?

In terms of the size of the unions and the density of membership, the differences between the 1970s and today are so obvious as to hardly need stating. According to the latest government statistics, there are 6.5 million trade unionists in Britain - just over 22% of employees. This compares to the high point of union membership of 13.2 million - with a much smaller workforce - in 1979. The majority now are in the public sector (3.84 million) and tend to be older and more highly qualified or skilled than the ‘average’ worker.2

A combination of economic and social change since the 1970s, such as the decline in manufacturing and the rise of the service and public sectors, alongside a conscious (and successful) strategy of weakening the potential power of organised workers through anti-trade union legislation, has decisively changed both the terrain on which British trade unions operate and their organisational form. The power of the union bureaucracy has been greatly strengthened at the expense of the rank and file, especially the workplace representatives and shop stewards. These were important elements of rank-and-file power in the strikes of the post-war boom in the late 1940s-60s, which saw action to advance living standards, as well as during the more defensive strikes against attacks on wages and conditions in the 1970s.

The legal restrictions put in place since the 1980s and the reduced industrial power of the movement have not only reinforced the power of the trade union bureaucracy, but strengthened tendencies towards compromise and class collaboration which have long been the hallmark of British trade union leaders. Hence the string of below inflation settlements negotiated by trade union leaders ranging from the FBU’s Matt Wrack to the RCN’s Pat Cullen.

The labour bureaucracy - a combination of trade union officialdom, Labour career politicians and apparatchiks - has, of course, its own niche and privileged position in capitalist society. Even when speaking the language of class war, its sectional interests cause this stratum to act as the labour lieutenants of capital in policing the working class.

This can be seen with initiatives such as Enough Is Enough, where trade union leaders such as Mick Lynch, Dave Ward and Eddie Dempsey worked hand-in-hand with aspiring Labour careerists and local hacks in order to contain and divert anger into pointless rallies and demonstrations. Naturally, the politics were kept to the usual banal platitudes of ‘a real pay rise’, ‘decent housing for all’, ‘tax the rich’, etc, and no accountable, democratic, structures were built. So, while Enough is Enough provided plenty of opportunities for inflating already inflated egos, the whole thing, inevitably, fizzled out ... along with other hopes of yesterday.

Momentum, the Socialist Campaign Group, Labour Representation Committee and Labour Left Alliance have likewise all withered on the vine in spite of, because of, the strike wave. Their politics have simply proven not fit for purpose.

Consciousness

If the trade union bureaucrats have been behaving true to form, what has been the impact of the year of strikes on the membership and wider working class? For both those taking part and the labour movement more generally, the strikes have both been a morale booster and raised class-consciousness, especially in disputes where the pay and conditions of the workers can be contrasted with the profits of the capitalists and the income of the senior managers.

Anyone who has taken part in a strike will tell you about the solidarity and sense of collective strength that is engendered by taking part in pickets, strike meetings and protests. Workers in dispute identify their enemies and friends and start to draw wider lessons about the nature of capitalist society. Reports in the left and even the bourgeois media provide plenty of examples of how industrial disputes can shift workers’ understanding of their place in the world.

This, however, does not proceed in a straight line and the hopes and expectations of some that the strike wave would produce a shift to the left and a rapid development of a revolutionary socialist consciousness have not borne fruit. Indeed, as shown in some trade union elections, the right has been strengthened. In Unison, for example, the Time for Real Change left group lost its NEC majority and the Socialist Party in England and Wales was reduced from four seats to just one (Hugo Pierre was elected from the Black Section).

The disputes themselves have been long drawn-out affairs, but the strikes have more been a day here and a day there. Also demands and struggles have been kept sectional, even when workers in a particular sector, such as the health service, are taking action over similar issues. The levels of coordination between unions at a national level have been minimal, although local groups of workers have attempted to build common action and demands in areas such as education, local government and the civil service. Most importantly, few of the disputes have truly resulted in victories, other than in some areas of transport and food production, where all-out strikes hit the employers’ profits and forced them to concede pay settlements in line with inflation. In other sectors, many of the settlements agreed by the union leaderships, even if trumpeted as victories, actually represent real wage cuts because they are quite a bit below the rate of inflation.

In response to these developments there is nothing wrong with calls from those on the left to build on the year of strikes and make attempts to overcome sectionalism by generalising the various struggles. But it is also important to undertake a sober assessment of where the movement might be heading and understand the limitations of strike action. After all, if a year of strikes has produced little in the way of tangible results, it is perfectly logical for trade union members, not just leaders, to look to the politics of moderation and the election of a Labour government headed by Sir Keir Starmer.

But some will never learn.

Alternatives

Take Socialist Worker; its whole raison d’être for decades has been the alchemy of spontaneity and turning the base metal of protests and strikes into socialist gold. At last, with big strikes happening, the picture was painted of Britain being on the cusp of a revolutionary situation rather than an altogether routine general election. Such economism entails either steering clear of high politics or, when there is high politics, there is tailism of the liberal bourgeoisie. But what is really important, in the meantime, is recruiting trade union militants to the confessional sect. Party Notes boasts of the SWP recruiting “well over 1,000 people since 2002” (June 19 2023). But, of course, few of them pay dues or attend meetings. Indeed it is a revolving door.

In a similar way Socialist Appeal - the British section of the International Marxist Tendency - also draws the wrong conclusions by overstating the impact of industrial disputes on class-consciousness. After the dreary years of auto-Labourism and pushing clause four socialism, albeit with a brief dalliance with Chavismo, the Scottish Socialist Party and other left nationalisms, they have suddenly discovered that they really are communists and that the crisis of capitalism internationally demands a new revolutionary leadership - now! The idea of entering into discussions with other groups with a view to forming an embryonic Communist Party, however, remains noticeably absent. Instead there is yet another attempt to build the confessional sect … this time by appealing to revolutionary minded students (amongst whom communism is increasingly popular). The aim is to get a thousand members!

Socialist Appeal wants to, needs to, keep its recruits excited. Very excited. So what we have is the upturn in strikes painted, yet again, as a prelude to an acute social crisis and the outbreak of social revolution. The danger is, of course, that the false perspectives of today lead to burnout and demoralisation tomorrow.

All the while, their old comrades in the Socialist Party in England and Wales, now under Peter Taaffe’s chosen heir and successor, Hannah Sell, doggedly push the totally stupid Trade Unionist and Socialist Coalition project - trying to create a Labour Party mark 2. Clearly the elementary lessons of the real Labour Party founded in 1900, the Labour Party mark 1, have not been learnt. At best Labourism leads not to socialism, but governing capitalism in the interests of the working class … and, when that all goes wrong, to a Tory government.

Comrade Sell and, following the Socialist Alternative split, her much reduced band of followers, cannot quite understand why trade union officialdom insists on sticking with the Labour Party and the real prospect of a Labour government headed by Sir Keir Starmer, rather than throwing in their lot with Tusc. True, members of Labour’s front bench keep a studied distance from strikers and picket lines. They must appear responsible before the City, the capitalist media and Britain’s US master. But, and this is crucial, a Labour government can actually deliver concessions to trade union officialdom and will almost certainly be less overtly hostile to trade unions than the Tories. Better, then, reasons the average trade union general secretary, to persuade, to pressurise, to plead with a Labour minister, than engage with the toytown Labourism of the Tusc project.

Clueless, Tusc carries on carrying on and in ever smaller circles. The SWP has gone, RMT has gone, even Chris Williamson has gone. Tusc’s politics are, of course, thoroughly economistic; high politics are almost totally absent. Despite that, Tusc candidates get farcical votes … one or two percent. That would not matter particularly … at least to begin with, if the politics were principled - but they are not.

Then we have the fragments and sects of one who hanker after the big time by uniting in this or that broad front. There are plenty of them on offer: Left Unity, George Galloway’s Workers Party, Socialist Labour Network, Peace and Justice and whatever Ken Loach comes up with next. All useless. All absurd.

Probably, however, after the next general election and a Sir Keir Starmer government, things will change. The larger sections of the organised left will be looking towards an alternative to ‘vote Labour …but’.

The choice is clear: building yet another broad front, or something really serious: building a mass Communist Party.