09.10.2025

The road from Eton College

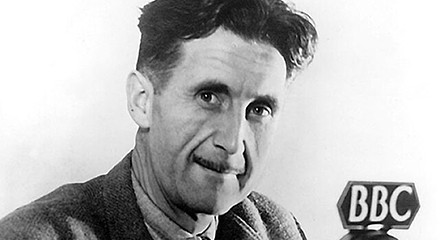

In the final article of his seven-part series, Paul Flewers grapples with a conundrum. Why did George Orwell, a self-proclaimed socialist, collaborate with the British state’s anti-Soviet propaganda machine?

The rightwing press had a field day with the discovery in 1996 of correspondence in the Public Record Office between Orwell and Celia Kirwan, who was a friend of Orwell’s, the sister-in-law of Arthur Koestler and an employee of the Foreign Office’s clandestine propaganda wing, the Information Research Department.1

The correspondence revealed that Orwell was asked in 1949 by the Foreign Office if he would help in the writing of material which could be used in its war of words against the Soviet Union. Orwell, terminally ill, turned down the invitation, but did provide the IRD with the names of 35 people, taken from a notebook containing 86 names. The papers repeated their celebrations two years later when the names in the notebook - or most of them - were finally revealed in Orwell’s Collected works.2 Once again, the right wing could claim Orwell as one of their own.

Why was he willing to collaborate with the murkier parts of the British state - the same sort of bodies which he had long denounced? Orwell was always a supporter of the lesser evil, and without ever renouncing his calls for the socialist transformation of Britain, he adopted a defencist stand during both World War II and the ensuing cold war, as he saw parliamentary democracy as a lesser evil than either a Hitlerite or Stalinist dictatorship. By the late 1940s, with Stalinist rule extending across eastern Europe, Orwell - by now a sick and pessimistic man - was willing to take whatever steps he felt were necessary to defend democratic rights in Britain. Furthermore, despite his suspicion of state institutions, he had no conception of the necessity for socialists to maintain their political independence from the state. This is why he was willing to make common cause with institutions that were bitter enemies of socialism, rather than propose a politically independent course.

In the covering letter to his list, Orwell stated that he wanted to help ensure that “unreliable” people would not be “worming their way into important propaganda jobs”. Orwell admitted to Kirwan that her “friends”, as he put it, probably knew all about those named by him, although he added that it was likely to be a good idea to have such “unreliable” people listed. He gave the example of Peter Smollett, an important official at the wartime Ministry of Information, who almost certainly had advised against the publication of Animal farm, and has since been revealed as a Soviet agent.3

The list itself is a strange collection. Only one, Smollett himself, actually was (as Orwell suspected) a Soviet asset. Many did not really require Orwell to point them out. EH Carr and Isaac Deutscher were not fellow-travellers, but were well known for dissenting from cold war orthodoxy. Some were well-known sympathisers of Stalinism, such as Walter Duranty, Sean O’Casey, Alexander Werth and commander Edgar Young; some, such as Tom Driberg and Kingsley Martin, had been soft on Stalinism; and others, including Michael Redgrave and JB Priestley, were politically naive individuals. Several were not exactly household names, such as the scientists, PMS Blackett, JG Crowther and Gordon Childe, and the journalists, Alaric Jacob and Iris Morley, but it is very likely – and, with Blackett and Childe, a fact - that they were on the radar of the intelligence services.4

Whether they were Stalinists without a party card or credulous believers in a happy land, far, far away, the whole thing with most pro-Soviet writers and intellectuals was that they were publicly sympathetic to the Soviet Union. A glance through the contents pages of Labour Monthly and other Stalinist publications would have provided a better list of them, and there is little doubt that Kirwan’s ‘friends’ regularly scanned them. The idea that the IRD would have commissioned any of them to write anti-Soviet material, or that they would have written any such thing, is laughable.

The rise of Stalinism posed a real problem for the left. Here was a state and a worldwide movement, emerging from a workers’ revolution and using the liberatory language of Marxism, which was extremely repressive, particularly towards its leftwing opponents and the working class. How could the non-Stalinist left respond to it?

When an article by Trotsky on the Moscow Trials appeared without his approval in the rightwing US press, he nonetheless responded that he and his colleagues wanted to expose the lies of Stalin to the widest possible audience. Moreover, he stated: “If I should have to post placards, warning the people of a cholera epidemic, I should equally utilise the walls of schools, churches, saloons, gambling houses and even worse establishments.”5 One of Trotsky’s last articles looked at the financial and secret police links between the Soviet Union and communist parties in Europe and America, and could quite easily have been used by the right wing against the ‘official communist’ movement.6

Other leftwingers, including Hugo Dewar, Peter Fryer and Walter Kendall, had articles presenting a leftwing critique of Stalinism published in rightwing journals such as Encounter and Survey. Victor Serge’s Destiny of a revolution was promoted in Britain by the National Book Association - a rightwing rival to the Left Book Club.7 None of this compromised the authors’ principles, as they retained their political independence, and the material published benefited the left more than the right.

Similarly, if leftwing anti-Stalinist material was used by the IRD or other western governmental bodies for their own ends, that did not necessarily reflect badly upon the authors.8 There is, however, a difference between this and working with institutions which have always been hostile to the aims of the left, and with whom cooperation can only work against the interests of the left. Although Orwell had little to offer the IRD, the fact that he was willing to collaborate with it shows that he had strayed into unacceptable behaviour for anyone on the left.9

Stalinism needed to be fought within the labour movement, and the fellow-travellers had to be exposed as venal or gullible apologists for Stalin’s regime. Nonetheless, this could only be done by a principled campaign that clearly differentiated itself from the right’s anti-communism. Those who wished both to combat Stalinism and maintain their socialist principles could not do so unless they maintained their political independence from the British state and its agents on the right wing of the labour movement.

And, just as Orwell’s theoretical limitations enabled his Animal farm and 1984 to be used by anti-communists around the world, they led him to collaborate with anti-socialist forces in Britain. He did not understand that the cause of socialism cannot be aided by collaborating with those who are its bitter enemies.

-

For a brief look at the IRD and its murky operations, see R Ramsay The clandestine caucus: anti-socialist campaigns and operations in the British labour movement since the war Hull 1998, pp6-7, 16-18.↩︎

-

G Orwell Collected works Vol 20, London 1998, pp240-59. Not all the names were released at the time; for the missing ones, see P Davison (ed) The lost Orwell London 2006, pp140-51.↩︎

-

G Orwell ‘Letter to Celia Kirwan’ Collected works Vol 20, p103.↩︎

-

D Caute Red list: MI5 and British intellectuals in the 20th century London 2022, pp222-34, 241-42.↩︎

-

L Trotsky ‘On Hearst’ Writings of Leon Trotsky 1937-1938 New York 1976, p265.↩︎

-

L Trotsky ‘The Comintern and the GPU’ Writings of Leon Trotsky 1939-1940 New York 1977, pp348-91.↩︎

-

V Serge Destiny of a revolution London 1937.↩︎

-

It also emerged that the IRD was promoting Orwell’s Animal farm to the extent of considering an Arabic translation (The Guardian July 11 1996).↩︎

-

About the only mitigating factor would be if the IRD was presented to Orwell in a way that disguised its sinister nature.↩︎