02.10.2025

The road from Eton College

In the sixth of his series of seven articles, Paul Flewers asks why George Orwell’s ‘whips woven of words’ fell so easily into the hands of his political opponents

Liberal and conservative champions of George Orwell have based their claim upon several factors - in particular his defence of aspects of bourgeois society, his wartime patriotism and deradicalisation, his incessant criticisms of other leftwingers, his siding with the USA in any war between it and the Soviet Union and, not least, his last two novels.

On these grounds, they then project what they feel his political trajectory would have been, had he lived beyond 1950. Of course, one cannot entirely rule out that Orwell might have ended up with the renegades from the socialist movement, whose hatred of Stalinism led them into the tender embrace of the ‘Congress for Cultural Freedom’. Not a few of his contemporaries did abandon any commitment to socialism - one such casualty being CA Smith, the former chair of the Independent Labour Party, of which Orwell was a member in the late 1930s, whose fear of undemocratic collectivism drove him precipitately to the right;1 another being Orwell’s friend, Franz Borkenau.2 But the evidence for the likelihood of any such evolution is indeed shaky.

We have seen that Orwell’s wartime patriotism and his defence of aspects of bourgeois society were central to his concept of the struggle for socialism, and therefore they were not an indication of any abandonment of it on his part. His criticisms of fellow socialists were, as Alex Zwerdling stated, intended “to reform and strengthen, not to discredit the world to which he pledged his loyalty: he was the left’s loyal opposition … his criticism was always designed as internal.”3 Orwell did indeed take pleasure in “rubbing his own cat’s fur backwards”, as Crick put it,4 but he did so precisely because he was a leftwinger: he considered it necessary to point to the various self-damaging and self-defeating foibles of which the left was guilty in his day (and - one must admit - remains guilty, mutatis mutandis, to this day).5 Again, it was not evidence of any renunciation of socialism on his part.

The radicalism with which Orwell entered World War II, peaking with The lion and the unicorn, had subsided somewhat by the end of hostilities. Nonetheless, Crick argued convincingly that despite this, “Orwell never changed his values after 1936”, and what we had was the replacement of “the wild hope that he had from 1936 onwards that ‘the revolution’ … was around the corner” by a “more realistic” view “in considering time-scales” of radical social change.6 And so Orwell criticised the Labour government for being too mild, stating in the spring of 1946 that it was “astonishing how little change” seemed “to have happened as yet in the structure of society”.7 He thought that the Labour government’s anti-communist purge was “part of the general breakdown of the democratic outlook”.8 He refused to join the Duchess of Atholl’s League of European Freedom as it had “nothing to say about British imperialism”.9 And he called for a United Socialist States of Europe, which was a longstanding far-left demand.10

Orwell’s siding with the USA if it and the Soviet Union came to blows had a definite reluctance about it, harking back to his choosing of the lesser of two evils in 1939: liberal-democratic Britain versus Nazi Germany. This was not the Atlanticism of rightwing social democracy, the strong identification with the USA and ideological, diplomatic and political subordination to Washington: rather, it was the standpoint of much of the Labour Party left in the late 1940s - one which soon shifted into a considerably more neutral, ‘independent democratic socialist’ course, between Stalinism and cold war orthodoxy.

Dilemmas

All the same, Orwell helped his political enemies by making his vocation as an advocate for socialism needlessly difficult for himself.

He avoided elaborating theoretical constructs by using sweeping statements that did not necessarily coincide with reality. He overplayed the degree to which intellectuals fell for the lure of Stalinism. He dismissed the idea that middle class socialists could remain lifelong adherents to the libertarian socialism that he championed - on that basis, how could he explain his own socialist principles, and that workers could educate themselves as socialists without becoming hacks or charlatans (although he knew many such people)? He stopped short of recommending workers’ control of industry as a means of forestalling the rise of a managerial elite, although this was well understood on the far left.11 He continually raised unnecessary dilemmas, and thus handed the initiative to his opponents.

Moreover, he had no properly formed concept of working class independence, that the institutions of the labour movement must maintain their political independence from those of the ruling class. This, together with his tendency to support the lesser evil,12 led him, notwithstanding his calls for radical social transformation, to back democratic British imperialism against its German totalitarian rival in 1939, and to declare that, if the cold war developed into a real conflict, he would side, if reluctantly, with the USA.13 It also led him into collaborating with an employee of the Information Research Department, an anti-communist wing of the foreign office that was set up by the Labour government in 1948.

“I know how, I don’t know why,” said Winston Smith, when confronted by the perplexing realities of Oceanian society.14 Orwell was a very good observer, capable of describing phenomena, often in a most evocative manner - he could point to the small details, in order to make the broad sweep simultaneously more intricate and more comprehensive. But he was far weaker in explaining phenomena. What lay at the root of the purloining of his literary legacy was his reliance upon critiques of Bolshevism presented variously by anti-communists and anarchists, which view the Bolsheviks not as a militant trend within the socialist movement, but as a discrete body led by a clique of power-hungry intellectuals - an elite-in-waiting even, outwith and parasitic upon the working class, and which consider the rise of Stalinism as the inevitable result of this leadership’s coming to power, rather than primarily as the unintentional consequences of the harsh objective pressures upon the Bolsheviks, once they were in power.

This approach either overlooks the democratic features of Bolshevism in 1917, and the vibrant relationship between the Bolsheviks and the Russian working class, or sees them as a disingenuous and dishonest ruse to win support. This was very much the view of his friend, Borkenau,15 and a key feature of various books that he favourably reviewed.16 The central feature of Animal farm - the theft of the revolution by an elite leadership - was expressed in an almost chemically pure form in an anarchist pamphlet which Orwell possessed. Declaring that “the present state of Russia” was “the inevitable result … of the Marxist-Leninist practice of centralisation and dictatorship” of the central committee of the Communist Party, it claimed:

Bolshevist tactics, wherever they are applied, will always lead not to the emancipation of the workers from the chains which now enslave them … They lead inevitably to the absolute of the totalitarian state. By allowing power over the instruments of production to pass out of their own hands into those of a so-called revolutionary government, the workers will achieve not liberty, but a slavery as bad or worse than that they sought to escape from.17

Altogether, it has to be admitted that, unlike the analyses of Bolshevism and its degeneration into Stalinism presented by many dissident Marxists, which were of some substance, Orwell’s observations in respect of the nature of Bolshevism and its mutation into Stalinism were unimpressive - little more than a few isolated and unoriginal assertions.18

The use in Animal farm of different sorts of animals to represent various social strata coincides neatly with the political theories that view the rise of Stalinism as the ineluctable result of the coming to power of a discrete group of intellectuals. The paralleling on this issue of the otherwise very different theories of cold war orthodoxy and anarchism has enabled this book to be used by opponents of socialism, with the proviso that Orwell’s liberal and conservative champions are obliged either to ignore or to steer delicately around his wholehearted support for the animals’ revolution.

This problem emerges in 1984, albeit in a different way. Looking beyond the absence in the narrative of the revolution that put the party into power and its subsequently becoming a ruling elite, the theoretical exposition in Goldstein’s ‘book’ is a series of timeless clichés of ineluctable processes, the struggles amongst ‘the High, the Middle and the Low’, with the Middle disingenuously eliciting the help of the Low against the High in order to become the new elite, with “the same pattern” always reasserting itself.19 Again, this fatalistic assumption has enabled the book to be championed by Orwell’s political opponents.

Orwell could describe totalitarianism, but he was quite unable to explain it. His nightmare vision of a super-Stalinist world was an exaggeration, but it did portray, albeit in an parodic manner, many of the truly negative features of the Soviet bloc at the end of the 1940s. Certainly, it was a good deal closer to that reality than the sugared portrayals in Stalinist publications of the time.20 But, unable to explain convincingly why the liberatory promise of the October Revolution became mutated into the horrors of Stalinism, or to present a socialist programme that could avoid the establishment of a new elite, his attempt to fight for a radical, democratic socialism was hijacked by cold war ideologues, who used the portrayal in his last two novels of the inexorable rise of a revolutionary leadership into an elite in order to promote the idea that any attempt to replace capitalism by socialism will lead to the frightful world of Oceania and Big Brother.

Whips and words

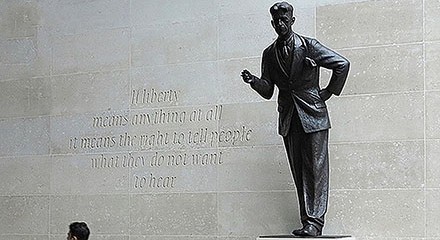

In his essay on Russian writer Fyodor Sologub, Yevgeny Zamyatin declared:

The whip has not yet been given its full due as an instrument of human progress. I know of no more potent means than the whip for raising man from all fours, from making him stop kneeling down before anything or anyone. I am not speaking, of course, of whips woven of leather thongs: I am speaking of whips woven of words - the whips of the Gogols, Swifts, Molières, Frances, the whips of irony, sarcasm, satire.21

Animal farm and 1984 were satires. Yet they failed in their purpose because, whilst they could describe the phenomenon they were satirising, they were unable convincingly to explain it - that is, to explain it in a way that differed from that of anti-socialists, or that did not rely upon theories of power-seeking - and therefore they could be - and they certainly have been - misused by Orwell’s adversaries.

Orwell’s “whips woven of words” fell readily into the hands of his political opponents - those who were and remain opposed to his vision of a democratic, libertarian socialism, and whose condemnations of viciously authoritarian regimes are, to put it politely, selective. Orwell did protest against the way in which his last novel was used as anti-socialist propaganda, but of the millions of people who have read Animal farm and 1984 within the ideological framework of the cold war,22 how many - or, better put, how few - have seen his protests or consulted those of Orwell’s writings which provide a far broader and clearer idea of his overall political outlook?

-

Smith claimed that “the rapid evolution towards central planning and state control” was “irresistible and irreversible” and that, in this process of incipient totalitarianisation, “communism is not socialism’s chief ally - it is socialism’s chief enemy … Capitalism is the enemy of yesterday and today; communism is the enemy of today and tomorrow” (Left May 1947). Not surprisingly, Smith soon found himself in the arms of the right wing, and was a founder of the red-baiting organisation, Common Cause.↩︎

-

Borkenau addressed the CCF’s founding conference in Berlin in 1950 with a speech which the conservative historian, Hugh Trevor-Roper, thought was “very violent and indeed almost hysterical” and which was received with “baying voices of approval from the huge audiences”, which he felt were “the same people who seven years ago were probably baying in the same way to similar German denunciations of communism coming from Dr Goebbels in the Sports Palast” (F Stonor-Saunders Who paid the piper? The CIA and the cultural cold war London 1999, p79.↩︎

-

A Zwerdling Orwell and the left New Haven 1978, p5.↩︎

-

B Crick ‘Introduction’ to G Orwell 1984 Oxford 1983, p4.↩︎

-

Besides the state-worship of various Stalinist countries, not a few intellectuals have been seduced by third-worldism, post-modernism and the wilder ends of ecological, identity and gender politics - the descendants of the trends cruelly satirised by Orwell in The road to Wigan Pier.↩︎

-

B Crick ‘Orwell and English Socialism’ Essays on politics and literature Edinburgh 1989, p201; see also J Newsinger Hope lies in the proles: George Orwell and the left London 2018, pp107-08.↩︎

-

G Orwell ‘London letter to Partisan Review’, May 1946, Collected essays, journalism and letters (CEJL) Vol 4, Harmondsworth 1984, pp220-21.↩︎

-

G Orwell ‘Letter to George Woodcock’ CEJL Vol 4, p470.↩︎

-

G Orwell ‘Letter to the Duchess of Atholl’ CEJL, Vol 4, p49.↩︎

-

G Orwell ‘Towards European Unity’ CEJL Vol 4, pp423ff.↩︎

-

For example, one could read in the ILP’s journal: “Nationalisation without workers’ control will lead, not to socialism, but to state capitalism - a trend definitely towards fascism … Workers’ control is the safeguard, the key to real socialist direction” (Left February 1946).↩︎

-

And so: “In politics one can never do more than decide which of two evils is the lesser …” (G Orwell ‘Writers and Leviathan’ CEJL Vol 4, p469.↩︎

-

G Orwell ‘Letter to Victor Gollancz’ CEJL Vol 4, p355.↩︎

-

G Orwell 1984 Harmondsworth 1969, p67.↩︎

-

Borkenau went so far as to assert that the Bolsheviks’ creation of “a party above the proletariat” and a regime that was always “a dictatorship over the proletariat … was not the unintended result of historical events, but the very aim for which the Bolshevik party had been consciously formed” (F Borkenau The totalitarian enemy London 1940, p208). So far as I can tell, Orwell did not endorse this assertion of totalitarian intent on the part of the Bolsheviks, as opposed to his support for this contention in respect of domestic power-seeking intellectuals. Borkenau was not the originator of this theory, which was to become a central factor in cold war orthodoxy: it had been expressed by, for example, the Czech democrat, Tomáš Masaryk, and the Russian populist, Benedict Myakotin, during the early years of Bolshevik rule (T Masaryk, ‘The Slavs after the war’ Slavonic Review June 1922; B Myakotin ‘Lenin (1870-1924)’ Slavonic Review March 1924. Borkenau presumably adopted the theory only after leaving the ‘official communist’ movement in 1929.↩︎

-

For example, N de Basily Russia under Soviet rule: 20 years of Bolshevik experiment London 1938; and Orwell’s review in New English Weekly January 12 1939; see also G Orwell ‘Marx and Russia’ The observer years London 2003, pp72-74.↩︎

-

The Russian myth London 1942, p28; see also Orwell’s pamphlet collection in Collected works Vol 20, London 1998, p282.↩︎

-

Just once, in 1946, did Orwell draw a different conclusion, one more akin to a Trotskyist analysis: “… in order to survive the Russian communists were forced to abandon … some of the dreams with which they had started out … From about 1925 onwards Russian policies, internal and external, grew harsher and less idealistic …’ (G Orwell ‘What is socialism?’ Collected works Vol 18, London 1998, pp61-62). Nonetheless, it still remains pretty thin stuff, when compared to other anti-Stalinist writers’ explanations.↩︎

-

G Orwell 1984 pp162-66.↩︎

-

Stalinist journalist, Alaric Jacob, stated that the society portrayed in 1984 is a “travesty” of what life was like in the Soviet Union. Jacob seemed to forget that the novel was presenting an intentionally exaggerated dystopian vision of the future. But, notwithstanding that, did not the Soviet regime institute a series of purges in the late 1930s and the late 1940s, in which many thousands of people disappeared into graves or labour camps after being forced to confess to false accusations? Were not official Soviet histories constantly rewritten, as yesterday’s heroes became today’s traitors? Did not the Soviet regime and the ‘official communist’ movement carry out breath-taking changes in policies? Did not Soviet citizens have to endure continual and intrusive police surveillance? Did they not have to put up with shoddy consumer goods, poor housing and indifferent food, whilst the party elite lived considerably better? True, Jacob - with Khrushchev’s ‘secret speech’ of 1956 safely in his bag - gave a passing nod to the “stupidities, errors and crimes” of Stalin’s regime (A Jacob ‘Sharing Orwell’s “joys” - but not his fears’, in C Norris (ed) Inside the myth - Orwell: views from the left London 1984, p82. But surely we have the right to ask, who came nearer to telling the truth about that regime - Orwell or the contemporary press of the ‘official communist’ movement?↩︎

-

Y Zamyatin A Soviet heretic London 1991, p221.↩︎

-

By 1971, over 20 million paperback copies of these two books had been sold around the world. Sales for 1984 in Britain between September 1983 and January 1984 stood at 430,000, and it was selling 62,000 copies per month in the USA in 1984. By 2003, the combined sales of Animal farm and 1984 amounted to over 40 million copies: see W Russel Gray ‘1984 and the massaging of the media’, in C Wemyss and A Ugrinsky (eds) George Orwell Westport 1987, p111; J Rodden The politics of literary reputation: the making and claiming of ‘St George’ Orwell New York 1989, pp49, 408; J Rodden Scenes from an afterlife: the legacy of George Orwell Wilmington 2003, p218.↩︎