11.09.2025

The road from Eton College

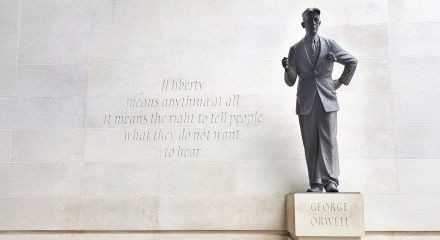

Seventy-five years after Orwell’s death, Paul Flewers turns to his ideas on collectivism and socialism in the third of a series of articles

George Orwell’s anti-war stance disappeared, as World War II drew near, although his shift to what can be best described as a revolutionary defencist standpoint was not so drastic when the underlying rationale is examined.1

As we have seen, he considered that the drift towards war would see the imposition of a totalitarian regime in Britain. However, when war broke out in September 1939, Britain was still a parliamentary democracy, and so, on the logic that even an imperfect democracy was preferable to fascism, he considered that the war against the Axis powers had to be supported.2

As Orwell moved from opposing a future war to supporting one in the present, he passed the ‘official communist’ movement travelling in the opposite direction, as it took an anti-war stance in the aftermath of the signing of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact on August 23 1939, and this intensified his already strong antipathy towards it.3 The pact dealt a heavy blow to the popular front bandwagon, and further popularised the already common view that the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany were “rapidly evolving towards the same system”, as Orwell put it in a review of Franz Borkenau’s The totalitarian enemy - a book which not only claimed that Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union were practically identical societies, but considered that the world faced a collectivist future, and that the quest for power was the driving force behind totalitarian regimes - ideas that Orwell shared.4

Orwell subjected to a withering critique the intellectuals whose sympathies had gravitated towards Stalinism. They, he contended, had merely exchanged their British patriotism and Christianity for another set of orthodoxies: “All the loyalties and superstitions that the intellect had seemingly banished could come rushing back under the thinnest of disguises.” Disillusioned with crisis-ridden Britain, they found in the Soviet Union “a church, an army, an orthodoxy, a discipline …, a fatherland, a Fuehrer …, patriotism, religion, empire, military glory …, father, king, leader, hero, saviour”: that is, “something to believe in”. This was the “patriotism of the deracinated”, the substitution of the seemingly dynamic, vibrant Soviet Union, thrusting ahead, brushing aside all obstacles, for the capitalist world which was struggling to pull itself out of economic slump, with country after country descending into fascist obscurantism.

It was easy for middle-class youngsters to see in the Soviet Union all the certainties that Britain provided their fathers and grandfathers, but which it could no longer supply. At first, Orwell tended to view pro-Soviet attitudes amongst British intellectuals as the result of their naivety, that they could “swallow totalitarianism”, because they had “no experience of anything except liberalism”.5 Nonetheless, his understanding that they recognised that, compared to the ineffectual floundering of Britain’s rulers, in Moscow there was an elite which could really rule, prefigured his subsequent conviction that they possessed a predilection for authoritarianism - a decided tendency towards power-worship which was no different to that expressed by supporters of Hitler or Mussolini - with a “cult of power”, which was “mixed up with a love of cruelty and wickedness for their own sakes”.6 Later on, he made the telling point that “it was only after the Soviet regime became unmistakably totalitarian that English intellectuals, in large numbers, began to show an interest in it”.7

Although Orwell recognised that there was no immediate danger of totalitarianism arising in Britain, he became ever more convinced of its likelihood in the not too distant future: “Almost certainly we are moving into an age of totalitarian dictatorships - an age in which freedom of thought will be at first a deadly sin and later on a meaningless abstraction. The autonomous individual is going to be stamped out of existence.”8

He noted the repression and degradation that was required for the establishment and maintenance of a totalitarian regime: “So it appears that amputation of the soul isn’t just a simple surgical job, like having your appendix out.”9 We then arrive at Orwell’s most perceptive observation on the subject of totalitarian regimes:

Totalitarianism has abolished freedom of thought to an extent unheard of in any previous age … It not only forbids you to express - even to think - certain thoughts, but it dictates what you shall think, it creates an ideology for you, it tries to govern your emotional life … The peculiarity of the totalitarian state is that, though it controls thought, it does not fix it. It sets up unquestionable dogmas, and it alters them from day to day. It needs the dogmas, because it needs absolute obedience from its subjects, but it cannot avoid the changes, which are dictated by the needs of power politics. It declares itself infallible, and at the same time it attacks the very concept of objective truth.10

Orwell considered that the elimination of objective truth - the removal of the ability of a person to obtain accurate information and thus be able to interpret and change society - was perhaps the most sinister aspect of totalitarianism. Moreover, he insisted that anyone who was “fully sympathetic” to the Soviet Union needed to “acquiesce in deliberate falsification on important issues” - not merely in respect of present-day events, but also when discussing its past: history itself needed to be infinitely malleable.11

Flowing from this, Orwell was insistent on the need for free expression of ideas: “Any Marxist can demonstrate with the greatest of ease that ‘bourgeois’ liberty of thought is an illusion. But, when he has finished his demonstration, there remains the psychological fact that without this ‘bourgeois’ liberty the creative powers wither away.”12

Orwell was adamant that socialism had to be built upon the gains of the capitalist era, and could not reject them without courting disaster.

This idea of preserving the better aspects of today’s society emerges in Orwell’s wartime strategy of revolutionary defencism. Its main thrust was that Hitler had to be defeated, but this was not possible unless a far-reaching social transformation took place in Britain; in short, a socialist revolution was necessary to win the war.13

Far from being ‘king and country’ flag-waving, Orwell’s patriotism was based upon two factors that were central to his concept of the struggle for socialism. Firstly, he considered that an internationalist appeal was ineffective, especially to the middle-class people whom he wanted to win to socialism; and, secondly, he wanted to defend those aspects of British life that he felt were worth preserving, including what he saw as the “gentleness” of British civilisation, the “liberty of the individual” and “the respect for constitutionalism and legality”. He recognised that these factors were a product of Britain’s specific historical development, rather than springing from innate national characteristics, and were basically contingent upon objective factors, as he recognised that the British ruling class would act like any other, were its power and privileges threatened. As he considered that the aim of socialism was “a world-state of free and equal human beings” and not any kind of nationally oriented affair or peculiarly British venture, it is clear that he saw these aspects as necessary features of a socialist society on a global scale: that is, in all countries.14

So how would the fight for socialism fare in a world seemingly hurtling towards totalitarianism? In The lion and the unicorn Orwell repeats his call for a new socialist party, and then calls for the state ownership of “all productive goods” - that is, land, mines, ships and machinery - plus “approximate equality of incomes …, political democracy, and abolition of all hereditary privilege, especially in education”, whilst recognising that “centralised ownership has very little meaning unless the mass of the people are living roughly upon an equal level, and have some kind of control over the government”. Yet he does not elaborate upon this “kind of control”. Indeed, Orwell goes so far as to say that, once the “productive goods” are the property of the state, the “common people” will feel that “the state is themselves”,15 thus virtually associating collectivism per se with socialism - something with which no Stalinist or social democrat would disagree.

The crucial issue of the control of the “productive goods” and the state machinery - the only way that collectivism can escape a totalitarian fate - remains vague: would this be possible via existing parliamentary structures, or would some other form of organisation, such as workers’ councils, be necessary?16

Once again, Orwell had painted himself into a corner.

-

Some commentators have viewed Orwell’s shift on the war as a fundamental change: V Richards (ed) The left and World War II: selections from the anarchist journal, ‘War Commentary’, 1939-1943 (London, 1989), p5; Socialist Standard May 1997.↩︎

-

Orwell explained his change of heart to Tosco Fyvel, stating that he realised that there was no danger of fascism in Britain: TR Fyvel George Orwell: a personal memoir London 1983, p100.↩︎

-

Orwell considered that the CPGB was led by people who were “mentally subservient to Russia”, and whose real aim was to “manipulate British foreign policy in the Russian interest”. Hence, when calling for an Anglo-Franco-Soviet alliance, a Stalinist was “obliged to become a good patriot and imperialist” (G Orwell Inside the whale London 1940, pp164-66.

Orwell’s conception was one-sided, especially when compared to Trotsky’s ideas. Trotsky recognised that this growing domestic patriotism had deeper roots and was leading to tensions between communist parties and Moscow (L Trotsky ‘A fresh lesson’ Writings of Leon Trotsky 1938-1939 New York 1974, p71. Perhaps this is why Orwell did not comment upon the remarkable episode when the CPGB’s general secretary Harry Pollitt and Daily Worker editor Johnny Campbell maintained their pro-war approach and voted against the Comintern’s anti-war line in October 1939 - even though this event, including their subsequent public grovelling and disingenuous self-criticisms (classic examples of what Orwell later called ‘doublethink’) was publicly known.↩︎

-

G Orwell, ‘Review’ Collected essays, journalism and letters Vol 2, Harmondsworth 1984, pp40-41; F Borkenau The totalitarian enemy London 1940, pp7, 32, 253. The prevalence in Britain of such theories of convergence is discussed in my The new civilisation? Understanding Stalin’s Soviet Union, 1929-1941 London 2008, pp131‑38, 184‑200.↩︎

-

G Orwell Inside the whale London 1940, pp166-69. On the other hand, Orwell considered that, unlike the intellectuals, the “common people” still believed in decency, fair play and the idea of “absolute good and evil” (G Orwell ‘Raffles and Miss Blandish’ Dickins, Dali and others New York 1946, p218.↩︎

-

. G Orwell ‘Raffles and Miss Blandish’ Dickins, Dali and others New York 1946, p218. Orwell favourably reviewed Bertrand Russell’s book on the subject of power, when it was published in 1938. He would not have disagreed with Russell’s assertions that revolutionary power was “very apt to degenerate into naked power”, or his equation of Soviet “political technique” with that of the fascist states: see B Russell Power: a new social analysis London 1938, pp120-21; G Orwell ‘Review’ Collected essays, journalism and letters, Vol 1, Harmondsworth 1984, pp413-14.

Subsequent observers have disagreed over the motives of the pro-Stalin intellectuals. Some claimed that they were naive - see especially D Caute The fellow travellers: a postscript to the enlightenment London 1973. Others followed Orwell: George Watson averred that “the literary evidence does not bear out the myths of innocence and self-deception”, as they knew that they were supporting mass murder: G Watson Politics and literature in modern Britain Basingstoke 1977, p70. However, naivety and power-seeking were just two of the motivations behind pro-Soviet sentiments; others were less reprehensible: for example, seeing Soviet schemes for state welfare and economic administration as having relevance in the capitalist world of the 1930s: see my The new civilisation? pp41-53 (note 4 above).↩︎

-

G Orwell James Burnham and the managerial revolution London 1946, p18.↩︎

-

G Orwell Inside the whale London 1940, p185.↩︎

-

G Orwell ‘Notes on the way’ Collected essays, journalism and letters Vol 2, Harmondsworth 1984, p31.↩︎

-

The Listener June 19 1941.↩︎

-

G Orwell ‘The prevention of literature’ Collected essays, journalism and letters Vol 4, Harmondsworth 1984, p85. As an example of viewing the past, Orwell pointed to a pamphlet from 1918 in his possession by Maxim Litvinov on the Russian Revolution that mentioned Trotsky and other “non-people”, but not Stalin, and asked what a present-day pro-Soviet writer would make of it.↩︎

-

G Orwell Inside the whale London 1940, pp172-73.↩︎

-

He argued this most succinctly in his essay, ‘Patriots and revolutionaries’, in V Gollancz (ed) The betrayal of the left London 1941, pp234-45. This position was shared by various leftwingers: for example, T Wintringham The politics of victory London 1941.↩︎

-

G Orwell ‘The lion and the unicorn’, Collected essays, journalism and letters Vol 2, Harmondsworth 1984, pp78‑81, 93, 102.↩︎

-

Ibid pp100-01, 120.↩︎

-

Orwell did raise this again, writing: “The whole question is who is to be in control.” Would it, he continued, be “wealthy men and aristocrats” or “representatives of the common people”? But once more this crucial matter is not resolved in any clear manner: G Orwell ‘London letter to Partisan Review’, April 1941 Collected essays, journalism and letters Vol 2, Harmondsworth 1984, p143.↩︎