15.05.2025

Watershed moment

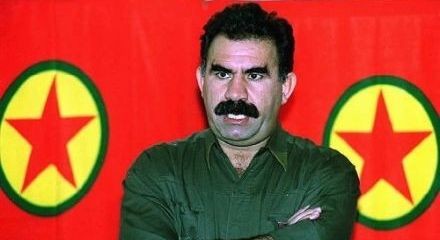

Abdullah Öcalan’s huge moral authority predictably prevailed. Esen Uslu comments on the many questions that arise following the PKK’s historic decision to lay down arms and end its armed struggle

Much-anticipated, the 12th Congress of the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) was held simultaneously in two separate locations last week, this while Turkey’s military operations continued. Nonetheless, the government provided a communications link for the PKK’s jailed leader, Abdullah Öcalan, to participate in the proceedings from his İmralı Island prison in the Sea of Marmara.

Obviously this was designed to overcome any opposition to his proposal to disarm and disband the PKK, an organisation that he helped found and within which, despite being held captive since 1999, he remains a towering moral authority. Apart from Apo, no one could convene a congress and get it to agree to lay down arms and convince PKK militants to consent.

However, the exact details of the communications he enjoyed have not yet been made public. But according to the scant reports, the congress duly approved Öcalan’s proposals outlined in his letter to the organisation and the general public, which was released at a meeting in Istanbul in January. As the full report, including agreed resolutions, has yet to be published, it is difficult to say with certainty what was agreed during the prolonged secret negotiations between the PKK and the government. However, based on the limited press release and the speeches of the PKK leaders, it seems that the agreements, whatever they may be, are being put into effect.

The process by which a successful 50-year-old guerrilla movement will be disarmed and dissolved is still unclear, as is the regional scope of the decision. Would the armed forces of the People’s Democratic Union (PYD), which formed the backbone of the Syrian Democratic Forces, be part of the deal? Or will the agreement signed between the SDF and the newly installed Syrian government, which accepts the integration of Kurdish forces with the new state security organisation, continue, while the SDF maintain its arms and structure? Initial reports from Syria suggest that the adopted resolutions do not cover this at all. Time will tell.

From the standpoint of Turkey’s president, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, the process did not start from a position of strength, or a need to democratise public life. On the contrary, the driving force was the fear of the impending collapse of the established order in the Middle East, and the redivision of spheres of influence under US and Israeli hegemony.

Syrian border

In practice, Turkey now has a new ‘land border’ with Israel through a now US-friendly regime in Syria. Donald Trump, of course, met with interim Syrian president Ahmad al-Sharaa in Saudi Arabia on Wednesday in Saudi Arabia. Under the nom de guerre Abu Mohammed al-Golani he had a $10 million US bounty on his head. Now sanctions have been lifted and Trump praises him as a “young, attractive guy. Tough guy. Strong past. Very strong past. Fighter.”

Nonetheless, Israel daily encroaches on Syrian territory. To bolster the new Syrian regime, Turkey needs to bring round the Syrian Kurds. Turkey is also acutely aware that the Syrian regime, which is based on a shaky coalition around al-Shara and his Islamist Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), could not withstand any threatened Israeli onslaught.

The HTS regime has proved incapable of winning the consent of the Druze and Alawite minorities living in the south and west of the country. The ongoing massacres perpetrated against them by forces aligned with HTS have demonstrated that the regime is unable to rule without resorting to terrorism. This ‘justifies’ an Israeli intervention under the guise of ‘protecting minorities’ from Islamist fundamentalists. Therefore, winning the Syrian Kurds away from their alliance with the US would be a big plus for Turkey.

The growing opposition to Erdoğan’s regime, with its one-man rule, is putting pressure on the coalition between his Justice and Development Party (AKP) and the far-right Nationalist Action Party (MHP). The traditional approach has been to increase pressure on the opposition through the security forces and the judiciary. The injustices and fabricated charges used to imprison opposition leaders have become so extreme that maintaining even a semblance of ‘democracy’ in the eyes of international public opinion is becoming near impossible. It is also becoming increasingly difficult to maintain the pretence that the regime’s aggression is merely a response to “terrorist activity”.

Öcalan was fully aware of these facts, and was prepared to take risks by ending all armed resistance and ‘continuing the struggle’ through unarmed politics, despite the limited democratic options available in Turkey. The move he initiated may secure some concessions from the regime, particularly with regard to amending the constitution before the next general election. For example, it would be regarded as problematic to imprison opposition leaders on the pretext that they are supporters of a ‘terrorist organisation’, when that organisation no longer exists.

However, expecting the AKP-MHP regime to democratise the state and society, as some in the press have prophesied, is nothing but a pipe-dream. Neither Erdoğan nor the state security apparatus has changed: they do not believe in peace, nor the will of people. They refer to their approach as the ‘consolidation of inner fortifications’.

Differences

A detailed analysis of the PKK press release and Turkish politicians’ speeches could shed some light on the apparent differences of opinion despite the general agreement. However, it is too early to read much into any of this.

Ertuğrul Kürkçü, a former MP and the honorary leader of the pro-Kurdish People’s Democratic Party (HDP), issued a statement after the congress. He declared:

These calls and resolutions are fuelled by the determination that new social relations and new states of consciousness have emerged in this half-century in the context of claiming rights. According to this determination, in the context of historical, social and political changes that herald the turning of an epoch, frontal warfare may not be the only path to freedom from a sociopolitical regime based on inequality, exploitation and domination.

It needs to be ascertained whether a new state of consciousness or a new set of new social relations has indeed emerged, as claimed. It also needs to be established whether a peaceful struggle is truly “the only path to freedom” from “inequality, exploitation and domination”.

In any case a watershed moment has passed, and we are now all eagerly awaiting the details of how the general agreement will be implemented, without letting down our guard. Will the Kurdish freedom movement be able to adopt a new organisational structure suitable for cooperating with working class forces in the coming struggle? Could the Turkish left contribute to the process in any way?