20.03.2025

The snowball effect

Mike Macnair details the long and difficult road to the 1875 Gotha congress of the ‘Eisenacher’ SDAP and ‘Lassallean’ ADAV. With unity there was an organisational take-off and an ability to survive harsh state repression

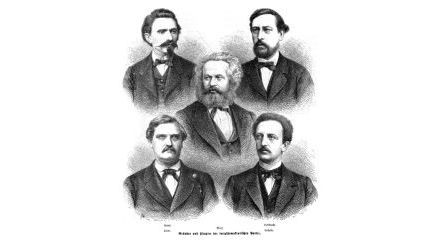

In May 1875 at a congress at Gotha two parties unified: the Allgemeiner Deutscher Arbeiter-Verein (ADAV - General German Workers’ Association), founded in 1863 under the leadership of Ferdinand Lassalle and identified with his doctrine; and the Socialdemocratische Arbeiterpartei (SDAP - Social Democratic Workers Party), founded in 1869 at Eisenach and identified as ‘Eisenachers’. They created the Sozialistiche Arbeiterpartei Deutschlands (SAP - Socialist Workers Party of Germany).

The Gotha fusion is politically two-sided for the left. On the one hand, the unification led to a ‘snowball effect’. At the fusion, the ADAV had 15,322 members and the SDAP 9,121. By 1876, SAP membership had risen to 38,000. In March 1876 the party was formally banned by the Prussian police, but the circulation of the party press was up to around 100,000, and in the 1877 Reichstag election the SAP obtained 9.14% of the vote and 13 seats. The SAP was illegalised under the ‘Anti-socialist laws’ of 1878-88, but was able to continue semi-legally through elections as a loophole, plus smuggling in newspapers from Switzerland; and, when the ‘anti-socialist laws’ were abandoned, the refounded Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands (Social Democratic Party of Germany) was the largest party in the country.

Unification leading to a snowball effect was repeated in Austria in 1888-89, France in 1905 and elsewhere. The SAP‑SPD’s strategic and organisational conceptions were at the foundations of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party and of Bolshevism.

On the other hand, the draft party programme put to the Gotha congress was very sharply criticised by both Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels in private correspondence with SDAP leaders. Published in 1891, as part of the discussion round the drafting of the SPD’s new Erfurt programme, Marx’s Critique of the Gotha programme has become one of the ‘foundational texts’ of Marxism, excerpted in the ‘Marxism’ taught to those university students who touch it.

Relying on this text, a significant part of the far left identifies Gotha with unity between ‘revolutionaries’ (the Eisenachers) and ‘reformists’ or ‘state socialists’ (the Lassalleans), on a programme that made undue concessions to the Lassalleans. This is then identified by this far-left narrative as the ‘original sin’ that led the SPD in August 1914 to vote for war credits and to pursue the Burgfrieden (‘castle truce’) policy of suppressing dissent and strikes.

This narrative is misleading. The ‘Lassalleans’ were not exactly ‘reformists’ and the ‘Eisenachers’ were not exactly ‘revolutionaries’. And the original-sin narrative of the history of the SPD has the wide credit it has on the left because of the intervention of academics from the Anglo-American security apparat after World War II, who actively promoted, in the interests of Nato, the idea that the only possible left politics were ‘right, but repulsive’ state-loyalist coalitionism (the SPD right; Labour; etc), or‘romantic, but wrong’ mass-strikism (Luxemburg; the young Trotsky; etc).

The real history is closer to the problems of modern left unification. The Eisenachers and Lassalleans were both heavily influenced by the arguments of the Communist manifesto and both were advocates of a radical break with capitalism.

ADAV

We begin in 1862-63.1 A group of German worker activists, who had recently visited London, approached the German liberals for support for universal suffrage - without success. Someone suggested they approach Ferdinand Lassalle - he had been an activist in the revolution of 1848, for which he had done some time. He had subsequently become something of a celebrity lawyer for his defence of Countess Hatzfeld in her divorce proceedings. In 1861 he had published Das System der erworbenen Rechte (‘The system of acquired rights’), a Hegelian account of the history of property law, with some unacknowledged borrowings from Marx - and one which made history end in socialism rather than (as in Hegel) in the ‘modern state’.

Lassalle, in response to the worker activists’ inquiry, issued his Open letter (April 18 1863). This was a longish pamphlet, which argued that trade unionism is useless due to the ‘iron law of wages’: that is, that the internal logic of capital will inevitably produce wages falling to subsistence levels. Hence, for the working class to achieve anything of substance, it has to take political action. The political action that it needs to take consists in the first place of campaigning for universal suffrage (meaning manhood - universal male suffrage). The second task is to campaign for state-backed cooperatives. These will be the means of abolishing the wages system.

The Open letter was enthusiastically received, and in May 1863 the ADAV was formed - in Leipzig, Saxony, probably for legal reasons (that the Saxon state was more likely to register a legal association than the Prussian state).2 It was an individual-membership organisation, like a trade union, but also ‘centralised’ by electing a president (Lassalle) with absolute power: this commitment was proposed by Lassalle on the basis of Hegelian arguments for the need for unity of will.3 Its political basis was the Open letter: that is, not a party platform, but agreement to Lassalle’s theory.

The liberals responded to this initiative by forming their own ‘workers organisation’, the Verein Deutscher Arbeitervereine (VDAV), politically committed to ‘self-help’ and opposition to state aid, and without the suffrage demand. Unlike ADAV, VDAV was a federation of local associations. It was much bigger than the ADAV, which reached around 5,000 members around the time of Lassalle’s death in September 1864; but the VDAV by that time had around 20,000.

Liebknecht

In October 1863 the ADAV recruited Wilhelm Liebknecht, another old 1848er. Liebknecht had been in exile working with Marx and Engels. But, finding it very difficult to make a living in London, he went back to Germany on the basis of an announced amnesty. (Marx also attempted to take the amnesty, with Lassalle’s support, but was excluded by the Prussian government on political grounds.)

By spring 1864, Liebknecht was in opposition to Lassalle within the ADAV, on two political grounds. The first was Lassalle’s kleindeutsch (‘small German’), policy on German unification: that is, support for German unification round Prussia without Austria, which Prussia would inevitably dominate. Liebknecht supported the opposed grossdeutsch (‘big German’) policy, to include the German part of Austria-Hungary. The second issue was suspicions of Lassalle’s dealings with Prussian minister-president Otto von Bismarck (these suspicions were confirmed much later): Bismarck thought the ADAV could serve as a political lever against the liberals, while Lassalle thought the Prussian monarchist conservatives might support the workers against the liberals.

Liebknecht’s opposition to Lassalle was cut short because in August 1864 Lassalle was killed in a duel. There was a brief moment afterwards where Liebknecht tried to nominate Marx as president of the ADAV, but Marx refused to stand: he was already busy with the founding of the International Workingmen’s Association - the First International, launched in September.

December 1864 saw the appearance of Jean-Baptiste von Schweitzer’s Der Sozialdemokrat newspaper (actually indirectly funded by Bismarck through an aristocratic proxy). Schweitzer was a lower-aristocrat playwright and author. He had been involved in radical politics for some time, but was prosecuted for allegedly picking up a teenage boy in a cruising area in a public park; this temporarily killed his political career, but Lassalle brought him into the ADAV.4

Liebknecht (and Marx and Engels) were suspicious of Lassalle’s, and hence also of Schweitzer’s, relations with Bismarck, but at the outset came on board: Liebknecht worked for Der Sozialdemokrat, and Marx and Engels lent it their names. Though this was supposed to be a pro-IWA initiative, in fact the December 1864 ADAV conference did not discuss IWA affiliation.

By February 1865 Der Sozialdemokrat was openly supporting the line of a Prussian-led Germany. Liebknecht resigned from the editorial board, and a week later Marx and Engels did the same. Liebknecht now went into opposition to this line in the ADAV, and won a majority in Berlin. The Prussian government in June, demonstrating its view that Schweitzer was useful to it, had Liebknecht arrested and deported from Prussia. He went first to Hamburg, where the Nordstern (North Star) newspaper was in opposition to the Lassallean ADAV leadership (but it went bankrupt), and then to Leipzig.

That said, in November 1865 Schweitzer was convicted of press crimes and lèse-majesté and imprisoned.5 Schweitzer was a politician and journalist Bismarck was willing to use; but not a fully-legal and loyalist one.

VDAV-DVP

In Leipzig, Liebknecht joined the liberals’ VDAV, and began to work with August Bebel to push it towards taking up political demands. In September 1865 the VDAV adopted the demand for manhood suffrage. In the same month, Bebel and Liebknecht and their co-thinkers in the VDAV in Saxony launched the Deutsche Volkspartei (DVP - German people’s party), a left-liberal party.

The result is two groups, neither of which looks that close to the ‘Marx party’. Neither the ADAV nor the VDAV-DVP was affiliated to the IWA - an issue that was central to Marx’s and Engels’ politicsin 1864‑1872. The ADAV was a ‘socialisation first’ group to the point of playing footsie with the conservative monarchists. The VDAV-DVP was a ‘democracy first’ group to the point of actually being a left-liberal movement and party.

In fact, between 1864 to 1872 Marx’s and Engels’ correspondence shows that they had ambiguous relations with both sides. They were not prepared to back Liebknecht and Bebel unequivocally. They equally were not prepared to wholly break with Schweitzer and the ADAV. They had closer relations with the direct supporters of the IWA in Germany, organised in a ‘network’ of local sections of the IWA promoted by another old 1848er exile, Baden revolutionary militia commander Johann Philipp Becker, from Geneva in Switzerland.6

June 14-July 26 1866 saw the Austro-Prussian War, rapidly won by Prussia. Bismarck funded a revival of Schweitzer’s Der Sozialdemokrat, which campaigned for Prussian victory; Schweitzer was amnestied. Meanwhile, Liebknecht had been agitating against the war before it broke out and, in August, Bebel and Liebknecht, through the VDAV-DVP, called a conference of anti-Prussian leftists, which adopted the ‘Chemnitz platform’. This combined calls for democratic change with the Lassallean idea of state-backed cooperatives (Engels was sharply critical).

In practice, however, the Austrian defeat had settled (until 1919) the debate between grossdeutsch and kleindeutsch perspectives. In addition, on the back of victory, Bismarck launched the North German Confederation with a (advisory) Reichstag elected by manhood suffrage and secret ballot, with two rounds of voting. It is fairly clear that Bismarck’s reasoning was the same as his grounds for supporting Lassalle and Schweitzer before: worker suffrage was to be expected to counterbalance the liberals in the interest of the monarchy.7 Both the ADAV and DVP won constituencies: Bebel was elected to the Constituent Assembly in February 1867, and then to the parliament; Liebknecht was elected to the parliament in August and Schweitzer in September.

Unity manoeuvres

Meanwhile, in May 1867 Schweitzer was elected ADAV president, and the party adopted a platform including democratic demands and internationalism - a move towards the IWA. The result was a split led by Countess Hatzfeld to form the “Lassallescher ADAV” (LADAV).

January 1868 saw the DVP get its own paper - or, more accurately, back Wilhelm Liebknecht’s Demokratische Wochenblatt (Democratic Weekly). Spring 1868 saw Schweitzer print a series of favourable articles on Marx’s Capital, volume one (published late 1867). In July, Liebknecht and Schweitzer made a private agreement for both the ADAV and VDAV-DVP to join the IWA. In August the ADAV congress voted to adopt the IWA’s political platform (not quite the same thing as joining). In early September, the VDAV congress voted by 69-46 delegates to join the IWA.

On September 8 the Leipzig police dissolved the ADAV as an illegal party. Schweitzer now abruptly changed course: Der Sozialdemokrat printed the claims of the VDAV anti-IWA faction at Nuremberg and denounced the VDAV. In October Schweitzer re-established the ADAV, this time as a Berlin-registered organisation. The ADAV now broke partially with its opposition to trade unions, beginning to create ADAV-controlled trade unions (ex officio president of all of them: Schweitzer).

Schweitzer’s abrupt turn away from unity caused problems in the ADAV. At its Easter 1869 congress, Liebknecht and Bebel were allowed to speak, and argued that, while they fought for unity, Schweitzer opposed it. Schweitzer called for personal vote of confidence, which passed, 43 delegates for, with 14 (representing a third of membership) abstaining. The Congress voted to increase the powers of the ADAV’s executive committee relative to the president.

On June 18 Schweitzer responded with a coup: he announced reunification with Hatzfeld’s LADAV, “return to Lassallean organisation”, abolishing the powers of the EC and returning them to the president, and giving five days to reply to a yes/no referendum. On June 26 ADAV dissenters Wilhelm Bracke and others in Demokratische Wochenblatt publicly denounced Schweitzer’s scheme and called for a unity congress at Eisenach on August 7.

The Eisenach congress then founded the Social Democratic Workers Party, SDAP. It was a unification between Bebel and Liebknecht and their supporters who had been in the VDAV; the ADAV dissenters (Bracke and co); and at least a considerable part of Becker’s network of local German sections of the IWA. The Demokratische Wochenblatt was ‘adopted’ by the party and renamed Der Volksstaat (The People’s State).

The Eisenach programme, the basis of the unification, has most of the faults Marx and Engels criticised in the Gotha programme in 1875. But the principle of having a programme was accepted by the former Lassallean dissidents. And the organisational form was a membership party - not a loose federation like the VDAV or a network of local groups like the IWA sections linked by Becker; but one which had an elected executive, not an all-powerful president. And, once the SDAP was underway, Liebknecht in 1870 broke up the VDAV-DVP alliance with left liberals by arguing for collectivisation of the land (starting with church land).

Towards Gotha

July 19 1870 saw the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian war (to continue till January 28 1871). Liebknecht and Bebel campaigned against the war, and both abstained on the war credits vote in the parliament. On the other hand, Schweitzer and Der Sozialdemokrat called for German victory.

Liebknecht and Bebel were initially isolated: the SDAP EC argued that this was a German war of defence against French aggression, which was also Marx’s and Engels’ initial view). However, the crushing defeat of the French at the battle of Sedan (September 1-2) transformed the visible politics of the war, and on September 5 the SDAP EC denounced a shift to war of conquest. First the EC, then Bebel and Liebknecht, were arrested.

The crackdown led SDAP membership to fall from 11,000 to 6,100. The German annexation of Alsace-Lorraine in January 1871 showed the truth of Bebel’s and Liebknecht’s diagnosis that this was a war of aggression. The declaration of the German Reich in the same month led to new Reichstag elections in March - though Bebel managed to retain his seat, both Liebknecht and Schweitzer lost theirs. Schweitzer then resigned as ADAV president: the effective end of his political career. The 1872 ADAV congress expelled him on the ground that there were “great, impressive grounds to distrust” him as an agent of the Prussian government.8

Meanwhile, the issue of the IWA became successively a driver towards unity, a ground for disunity, and - like German unification - a moot issue. The background was the entry operation of the Bakuninists in the IWA between June 1868 and September 1872, and the related debates.9 In 1868 the IWA had been a driver towards unity - though Becker’s network of local sections of the IWA was a (weaker) competitor to both the ADAV and DVP.

In 1869-70 Bakunin’s polemic against the Eisenach programme was a part of the struggle.10 In March 1870, the general council’s ‘Confidential communication on Bakunin’ (drafted by Marx) for the first time characterised the ADAV as a sect - effectively the IWA took sides with the SDAP.11 In summer-autumn of 1871, the split in the IWA was consummated. The London congress of the IWA was denounced by the Bakuninists and the ADAV; on the other hand, the Bakuninist conference in Switzerland was supported by the ADAV.

In September 1872 the Hague conference of the IWA formally adopted a commitment to political action and expelled the Bakuninists - but also moved the general council to New York, which turned out to be a killer for the organisation. This was not immediately apparent, but the IWA issue between the SDAP and the ADAV was now moot.

In March 1872 Bebel and Liebknecht were convicted of treason by campaigning for a republic, and jailed for two years. In August 1872, the SDAP congress issued a new call for unity with the ADAV, and prohibited Volksstaat polemics against them. In reality, polemics and debates continued; but the SDAP leadership continued to press for unity, while the ADAV rejected it. In autumn 1874, however, factional warfare in the ADAV led both sides separately to approach the SDAP for unity. Bebel was still in jail, but the SDAP leadership seized the moment, and the ADAV and SDAP announced unity negotiations on December 11.

By the end of that month the negotiators had agreed an organisation statute, which retained the principle of individual membership, as opposed to federation, but otherwise broke with Lassallean ‘centralism’. By March 7 1875, they had agreed a draft programme - the famous, or infamous, Gotha programme - which reflected compromises between the Eisenachers and the Lassalleans. It was this draft that Marx and Engels both criticised. (Lars T Lih has pointed out that important changes were made in the programme actually adopted).12

It is certainly true that the programme contained compromises with the Lassalleans. But the fact that it was a programme, rather than agreement to theory, was a capitulation on the part of the Lassalleans. And, like the Eisenach programme, and like the earlier six points of the 1838 People’s Charter, the 1848 ‘Demands of the Communist Party in Germany’ and the later 1880 Programme of the Parti Ouvrier, 1889 Austrian Hainfeld and 1891 German Erfurt programmes, it was a politics-first document.

As I already indicated, the result of the unification was a very rapid take-off - leading to an almost as rapid illegalisation under the 1876 ban and 1878-88 ‘anti-socialist laws’; but also the ability to survive and prosper in illegality, using the combination of electoral activities with smuggling in newspapers.13 It was this approach to organising in illegality that Lenin sought to urge on the Russians in What is to be done?

This was not a broad-front party. It was a unification of two groups, which had emerged through a process of splits and fusions arising originally out of one group, the ADAV, with a series of splits, including that in 1869, which created the Eisenach SDAP. Lassalle was significantly influenced by Marx, although he muddled his arguments as well as plagiarising some of them; as already mentioned Schweitzer published strongly positive reviews of Capital volume one in 1868.

Political

The ADAV was in a certain sense a ‘socialisation-first’ party, but it was a political party which fought for manhood suffrage as the first step to the proposed state-backed cooperatives. In the debates in the 1860s international workers’ movement, the Lassalleans were in this sense closer to the ‘Marx party’ than to the Bakuninists, who argued for general-strikism; or to the Proudhonists, who argued for self-help cooperatives and political abstention; or to the Blanquists, who argued for conspiratorial preparation for insurrection.

It is all too easy to forget the context of the German socialists, existing on the margins of legality. Becker was engaged in clandestine correspondence from exile. When the ADAV adopted part of the platform of the IWA, the police promptly dissolved the organisation. And so on. Both Lassalle in 1863, with registering the ADAV in Leipzig, and Bebel and Liebknecht in 1865, with forming the DVP, are trying to find ways to conduct political work legally (as far as possible) in a regime that sharply limited legal political action.

That the result turned out to be, in the SAP-SPD, a highly successful model was perhaps serendipitous. Political parties, beginning around 1678-83 in England, were organised on the pattern of parliamentary caucuses, plus national clubs, plus local clubs. This is a wonderful mechanism for organising the capitalist class, because the national caucuses and clubs are nexuses of national-level bribery, while the local clubs are nexuses of local bribery. This institutional form - which persists to this day in the US Republican and Democrat parties and the British Conservative party - was still the form used by Chartism, and was still conceived by Marx and Engels as the form of the workers’ political party in the March 1850 Address: “The speedy organisation of at least provincial connections between the workers’ clubs is one of the prime requirements for the strengthening and development of the workers’ party.”14

Lassalle’s theoretical conception in the System der erworbenen Rechte, being Hegelian, entailed the idea of the state bureaucracy as expressing the general interest, argued by Hegel. But his political proposal in trying to make deals with Bismarck was the idea that the working class can ally with the feudal aristocracy against the bourgeoisie. This had a certain basis, in that the ‘Ten-Hour Day Act’, the Factories Act 1847, passed the UK parliament with Tory votes over Liberal opposition. Indeed, in 1893 Engels argued in a letter to Bebel that under some circumstances it might be desirable in Britain to call for a tactical Tory vote in order to force concessions from the Liberals.15

Engels’ point in the letter is that Keir Hardie’s advocacy of a Tory vote does not look tactical. Lassalle’s argument in 1863-64 similarly does not look tactical. And Schweitzer, who succeeded him, was plainly dependent on Bismarck.

The most fundamental point is that it is deeply mistaken to see the Gotha unification as the ‘original sin’ that led to the SPD’s collapse in 1914. In the first place, as RH Dominick argued in his 1982 biography of Liebknecht, it is probable that Marx’s and Engels’ judgment that the ADAV would collapse if left alone was just wrong. Dominick makes the point that the ADAV had already survived several splits, and that the SDAP membership would have been deeply unhappy with a turn away from unity.

Secondly, and more fundamentally, though the cult of Lassalle as founding hero persisted in the SPD, the people who became the revisionist right were not, in the main, ex-Lassalleans. Eduard Bernstein, for example, was Engels’s literary executor. Georg von Vollmar was a mass strike advocate in the 1880s, before becoming an advocate of reform coalitions with the liberals in 1891. And so on.

Indeed, the SPD was in summer 1914 planning for a strike campaign to demand manhood suffrage in Prussia.16 But then this was overtaken by the war crisis. And shortly before the war-credit vote, Reich chancellor Bethmann-Hollweg met with the SPD trade union leaders, with the stick: we are about to be invaded by the Russians (which actually happened, but was defeated at Tannenberg by August 23-30 1914, so that the war ended up being fought on Russian soil). And the carrot: deliver SPD votes for war credits, and we will deliver major concessions to the trade unions. And the unions did, in fact, deliver.

In short, the standard far-left version, according to which the Gotha unification is the original sin of the SPD, just does not work.

This article is adapted from Mike Macnair’s talk to the Why Marx? ‘Our history’ series.

-

A great deal of what follows is from RH Dominick III: Wilhelm Liebknecht and the founding of the German Social Democratic Party Chapel Hill NC 1982, which is thoroughly documented.↩︎

-

This was before the completion of German unification. Saxony and Prussia were independent states.↩︎

-

For example, against Julius Vahlteich, who was expelled and went to the IWA, later to the SDAP: Lassalle quoted in CW Fölke Zweck, Mittel und Organisation des Allgemeinen Deutschen Arbeiter-Vereins Berlin 1873, pp21-22, 29-30.↩︎

-

H Kennedy ‘Johann Baptist von Schweitzer: the queer Marx loved to hate’ Journal of Homosexuality vol 29 (1995).↩︎

-

Derived from the Roman laesae maiestatis (closer to English law: treason); but the offence used against Schweitzer and occasionally against other socialists down to 1918 was closer to the English law, ‘seditious libel’ (abolished in 2009).↩︎

-

RP Morgan The German Social Democrats and the First International 1864-1872 Cambridge 1965, especially chapter 3.↩︎

-

See, for instance, GB Pittaluga, G Cama and E Seghezza ‘Democracy, extension of suffrage, and redistribution in nineteenth-century Europe’ European Review of Economic History, vol 19 (2015), pp317-34.↩︎

-

Quote from Dominick p104.↩︎

-

A useful summary is in J-C Angaut ‘The Marx-Bakunin conflict in the First International: a confrontation of political practices’ Actuel Marx (2007); translation: shs.cairn.info/article/E_AMX_041_0112?lang=en.↩︎

-

libcom.org/article/critique-german-social-democratic-program-mikhail-bakunin.↩︎

-

LT Lih, review of KB Anderson’s and K Ludenhoff’s new translation of Marx’s Critique: platypus1917.org/2023/06/02/a-review-of-karl-marxs-critique-of-the-gotha-program.↩︎

-

See, for example, VL Lidtke The outlawed party Princeton UP 1966.↩︎

-

www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1847/communist-league/1850-ad1.htm.↩︎

-

Engels to Bebel, January 24 1893: www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1893/letters/93_01_24.htm.↩︎

-

J-U Guettel ‘Reform, revolution and the “original catastrophe”: political change in Prussia and Germany on the eve of the First World War’ Journal of Modern History 91 (June 2019), pp311-40. The meeting between Bethman-Hollweg and the trade union leaders is in H Strachan The First World War, volume 1, To arms Oxford 2001.↩︎