12.09.2024

Fiction: utopian and scientific

We all have our ways of weighing up the probabilities, of orienting our moral sense. In his intriguing talk to Communist University 2024, Paul Demarty examines the changing face of utopian literature and the role it, and science fiction, can play in Marxist politics

This is a talk about science fiction, and its relationship to the utopian imagination. This is not a new topic in the literature, to put it mildly. Fredric Jameson has been stomping around in it for decades, as well as others before him and many others after him.

But this is not a Historical Materialism panel on the subject: we are here at Communist University, after all, and our overall collective job is directly political: to orient the Marxist left, so far as we are able to do so with our modest platform. We have a tradition of doing so beyond direct reference to immediate struggles or political history, by covering mass culture, or paleo-anthropology, or philosophy. This is not the first talk I have given on roughly this subject area.

So let us talk about utopianism as we know it, as good, well-catechised Marxists. Throughout the whole period that social scientists and others call, with maddening vagueness, ‘modernity’, there have been attempts to set up utopian societies (indeed, before that too). They have mucked along for a time, before being destroyed either by internal or external factors. By the time Marx and Engels reached maturity in the 1840s, there were no end of such prescriptions, and attempts to carry them out. They generally failed. Both sides of this influenced Karl Marx and Fredrick Engels - the inexhaustible appetite for such schemes, and the fact that they were apparently doomed.

Their response was twofold: firstly, to unite this socialism with the developing class politics of the proletariat, most especially in the form of Chartism (this I leave to one side), and secondly, to try to put socialism on a scientific footing. Why did these utopias fail, so reliably, in all their diversity - bureaucratic and anarchistic, secular and religiose? It was one of Marx’s and Engels’ greatest ideas to bring, as best they could, the scientific method to such investigations: to subject the condition of the toiling classes to unsparing analysis, and draw out of that the hypothesis that it was the proletariat alone whose specific conditions of life comported in both the short and long term with a new, communist society.

This is a very crude picture, but I draw it only to make a point about the relationship between Marxism and the various utopianisms. It was not simply a rejection. Marx and Engels criticised utopians in the name of the ‘real’ utopia; but it was in the very nature of a real utopia that it could not be planned out in advance. It depended instead on the action and consciousness of the broad masses. Our job was to sweep things away, to clear a path for later transformations we could only barely outline. But Marx and Engels had learned from the utopians, I think. It is a matter of dialectics: Marxism is not merely non-utopian. It is the negation of the negation that was utopianism. It ‘sublates’ utopianism, in the Hegelian jargon - both abolishes and in some sense absorbs it.

Modern period

Beyond the historical record of the utopias that people attempted to build - from, in the western context, the communism of consumption attributed to the earliest Christians in the Acts of the Apostles, to the true levellers and Anabaptists of the 17th century, and on to the Owenites and Fourierists of the 19th - there is the literary record. That is, above all, the strange history of the ‘utopian novel’.

The word, utopia, originates in the earliest such text in the modern period, Thomas More’s Utopia. In it, the narrator meets a stranger, Raphael Hythloday - the surname meaning “peddler of nonsense” - who has returned from an obscure island governed according to a strict and communistic set of laws, which he proceeds to lay out extensively (Utopia, likewise, means ‘nowhere’). Its rationalistic form of government is somewhat parodic, but is nonetheless contrasted with the England of More’s day, of the enclosures and - as Hythloday puts it - “sheep eating men”. Marx’s chapter in Capital on primitive accumulation starts exactly here.

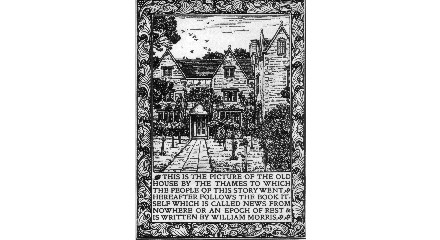

The sheep, of course, continued to eat up men for centuries; by Marx’s day, it was the machinery of the factory system with the greater appetite, and it is no surprise that this period saw a great flourishing of utopian literature. Any number of examples could be cited, but I have chosen as an exemplary text William Morris’s News from nowhere. It is the best account of what a post-Marx utopian novel (or, as the indefatigable antiquarian Morris insists, utopian romance) has to offer us.

It begins with the narrator - clearly Morris himself - walking home from a meeting of the Socialist League, a semi-anarchist, socialist sect influenced by Marx and Engels, but not very much approved by them. The meeting has been taken up with directionless discussions of the nature of the future society, sketched with loving mockery by a man who clearly enjoyed such gatherings. He falls asleep in his Hammersmith home in 1890, and wakes up 150 years later. Things, to put it mildly, have changed. London is more picturesque; salmon leap down the Thames. He meets a boatman, and is astonished to discover that he is no mere servile worker, but a happy man with a rich life. By and by, he is introduced to an old man called Hammond, who spends a great deal of time explaining the rules of this new order, with a long and violent chapter recounting the course of the revolution that brought it about. Morris ends up boating up the Thames with young lovers going to take in the hay harvest in the country - not a chore, but a great pleasure.

The worry that hangs over the whole society is that they might run out of work. After all, by now, they have pulled down all the ugly buildings and rebuilt them to (let’s be honest) Morris’s aesthetic specifications. Their goods endure: there is no need for relentless replacement. The sexual morality of the age is both strangely Victorian in its worship of delicate femininity and strikingly modern in its insistence on free love and readily available divorce (rather magnanimous of the famously cuckolded Morris, all told).

News from nowhere is atypical of the utopian text of its day in its anarchistic nature, in its insistence that, though the point of all economic activity is the fulfilment of men and women as they are, such fulfilment is ultimately down to the individual. We meet people who stubbornly resist the changes and grumble about the good old days (who are largely treated as harmless eccentrics). It is typical, on the whole, in its form. But for the very long chapter on the course of the revolution, which takes in desperate times and a Gatling gun attack on a Trafalgar Square crowd, it is very reminiscent of other examples of the genre. There is a stranger in town, and people patiently explain the rules of the new world to him. It can be compared quite directly to Edward Bellamy’s Looking backward - a more ‘rational’ utopia that Morris despised for its statism, elitism and indifference to aesthetics.

The problem for the utopian novel, as Jameson among others noticed, is its tendency to be - let’s face it - boring. It dresses up as a novel, or a romance in Morris’s case, but there is little in the way of narrative tension or conflict. They all tend to devolve to long descriptions of how things ought to be. News from Nowhere is not quite the worst offender here, simply because Morris places the ‘action’ in the English countryside, has his narrator fall in love, and - unsurprisingly for such an incorrigible, capital-R Romantic - is overall keen to stress the beauty of the new world, the faces not prematurely aged by cruel factory labour, the nature renewed by people who dare to care for it, and the care with which all objects of use, from houses to hand tools to meals, are crafted by people in no hurry to appease capital.

There is a rhapsodic effect - a sense that we are with Morris in a happy dream, and we share with him a melancholy feeling that we must eventually leave it for the dark satanic mills and nuclear arsenals of the real world. Still, it is hardly a thrilling page-turner. It reminded me a little of the ‘Fellowship of the ring’, the most aimlessly bewitching volume of The lord of the rings. But, while the ‘Fellowship’ gloriously fails to get to the point, the aimlessness in News from nowhere just is the point: a tour of a world in which labour is life’s prime want.

Revisionism

I can find no evidence that Ursula Le Guin was a fan - or a hater - of William Morris. Reading her greatest entry into the canon of utopian literature, The dispossessed, directly after News from nowhere, produces the distinct impression that she must have been; but the known sources for this book are rather anthropological and - in the field of politics - the ideas of the eco-anarchist, Murray Bookchin. Her novel stands in relation to a Morrisian craft utopia, just as the revisionist western film relates to the heroic cowboy movie of the classical Hollywood era. Those later films were not merely telling different, more morally ambiguous stories in the same setting as the more naive films of the earlier era: in an important respect, by telling those stories, they changed the setting. It was not just the western that was ‘revised’, but the west itself.

‘The dispossessed’ is an answer to the question, ‘What if you attempted to build Morris’s Nowhere not in a verdant, temperate England, but a desert?’ It takes place across two planets (each of which considers the other “the moon”). One, Urras, corresponds quite closely to the Earth of the cold war period in which she wrote it - large, rich, abundantly habitable and riven with great-power conflict between A-Io, a capitalist and patriarchal society, and Thu, some kind of socialist dictatorship (little is revealed of it in the course of the novel) - quite obvious analogues of the USA and USSR. The other, Anarres, has been gifted to the devotees of a revolutionary movement of anarchists centuries before. It is mineral-rich, but largely arid. It is clearly a dependency of Urras, suffered to exist in return for the export of minerals. Yet, though life is hard, the system just about works. And it is Morris’s system, or thereabouts: people choose their own labour, up to a point; they are sexually liberated - now by the standards of the 1970s rather than the 1890s. Neither of these utopias has much use for formal schooling. Neither has any prison.

The story centres on a man from Anarres called Shevek - a scientific prodigy who may be on the brink of a breakthrough in the understanding of time itself. He becomes the first person to leave his planet for that great, verdant moon of Urras - a guest of the quasi-American A-Io, who have uses for his grand ideas. He has to leave, in the end, because Anarres does not have much use for them: they are too metaphysical, too speculative. (Shevek’s theory of time seems to me equal parts Einstein, Bergson and Heidegger.) He becomes embroiled in cheap academic politics, and, in order to make use of his theory, has to escape. His escape, however, is to a far more dangerously political world; his faith in the precepts of ‘Odonianism’, the Anarrist creed, is rather reinforced by his contact with class society, especially when he is drawn into a disastrous insurrectionary strike - put down, like Morris’s protestors in Trafalgar Square, by machine gun fire.

Le Guin’s novel is subtitled “an ambiguous utopia”, but you hardly need the hint. Her Anarres is, in some ways, a successful revolutionary society, but one creaking at the edges. Years of famine have dried it out. Its social sanctions against ‘egoism’ and ‘altruism’ - the twin evils of self-worship and condescending charity - have hardened into a prickly conservatism. Inspired by one genius, it no longer has room for any others.

So far, so typically dystopian: but then there is Urras itself - a whited sepulchre of a planet. Shevek is flummoxed by a society which combines a superficial and pervasive eroticism in aesthetics - he is captivated by the sensuous curves of a table - with strict sexual norms and subordination of women. He is agitated by the total absence of the poor from his life, when his own world could not sustain such ruling-class opulence even if it had such a class. It is his progressive alienation from his new surroundings that leads him to the ill-fated revolutionaries - something only possible because even this exile can see the virtues of ‘Odonian’ social organisation.

It is thus, as advertised, ambiguous. I would characterise the novel as a rebuke to exactly the critique it invites of Anarres, of the ‘inevitable’ suppression of individual genius, simply by refusing shelter in the comfort blanket of a vague freedom. It is acutely aware of the freedom sacrificed for the enjoyment of elite classes - an enjoyment all too comfortably in the rear-view mirror of Morris’s Nowhere.

Both have in common that the revolution itself is already accomplished - whether, in Morris, in its home country, or in Le Guin, the colony to which the revolutionaries are exiled. Kim Stanley Robinson’s Mars trilogy takes us a step further, and presents that process in the narrative itself. A hundred people - 50 men and 50 women, mostly scientists - are sent off to Mars, to begin a research colony. Most are American or Russian (when Robinson was writing, in the early 1990s, such a division was still roughly plausible). The earth they leave behind teeters on the edge of global war. Many hope to make a new society, without the defects of the old. The story is fundamentally the story of their disagreements: between those who want to terraform, and those who want to preserve this new planet as it was; between those who want to make Ares into an Anarres, and those playing politics with the bigwigs back home; and finally, the (again) ultraviolent action taken by a collapsing Terran society against the restive Martians.

Robinson’s generic apparatus is that of hard science fiction. He gives us, as best he can, an unromantic view of building a new world subject to constant sub-Antarctic temperatures, toxic atmospheric conditions and relentless radiation bombardment, which rather makes Anarres sound like Butlins. The question of terraforming agitates the colonists most of all, but combines with more high-political concerns. Some support terraforming to allow a better society than collapsing, capitalist Earth to be constructed - notably the anarchistic Russian socialist, Arkady Bogdanov - clearly a nod to Alexander Bogdanov, best known to this crowd as the target of Lenin’s Materialism and empirio-criticism and a left factional opponent within the Bolsheviks, but also the author of a utopian novel, Red star, about the colonisation of Mars. The opponents of the terraformers, led by the American Ann Clayborne, worry that terraforming will destroy the very thing they are supposed to be there to study: Mars itself, as it was and has been, roughly, for billions of years.

The terraformers and the anti-terraforming ‘Reds’ - and the different political factions within them - are not to be left alone to sort it out for themselves. The old world creeps back into their affairs, with the mighty transnational corporations of the old world, and their UN proxies, gaining bridgeheads on Mars. The process is rather like the taming of the American west as it really was - not a matter of heroic sheriffs taking on outlaw gangs, but a violent tale of robber barons and Pinkertons. The utopians confront the full power of the state and the private empires that have somewhat superseded it on Earth, in a battle that plays out over centuries and three fat volumes of text.

These three works arrange themselves, as it were, concentrically. Morris’s Nowhere shows us the accomplished Utopia, triumphantly unassailed by hostile forces, with its fully worked-out morality, its aesthetic sense, its internal enemies mere cranky old men. The dispossessed gives us the Utopia poised on the edge of the precipice, its survival constantly threatened by hostile external powers and the threat of scarcity. It depends on the explicit commitment of its people to the social morality - Odonianism is lived out, as Aristotle’s ethics would put it, as continence rather than virtue, an effortful achievement rather than a natural habit. This tends to harden that morality into a conformist legalism, which in turn sets the events of the novel on their way. Despite Anarres’ dependence on A-Io, the true threat to the Utopia is internal, in the dreaded possibility that it might curdle into some tyranny like Thu.

Robinson’s trilogy is a step further back than that. There are vicious internal challenges, in the bitter divisions between the rival factions, most of which are utopian in the sense that they have a clear vision of the overall social good, defined against an unacceptable present. Yet they must all reckon with the attempts of the old to drown the new in blood. It is not a tale told by an old man, like Morris’s Hammond, eccentrically attached to a history all but forgotten by the happy folk of Nowhere. Nor is it briefly re-enacted in the present, as in Le Guin’s disastrous insurrection. Robinson’s characters have their ideals put to the test for real, and are pushed into unlikely alliances, which are then broken at the next upheaval.

Among the internal enemies of Robinson’s utopians are those whose ambitions depend on support from the home world. These are all Americans. There is John Boone - already a celebrity for having been the first man on Mars on an earlier mission, himself aligned with the more socialistic colonists but hoping to get support from governmental institutions like the UN for his project. Phyllis Boyle, a fairly typical Evangelical type, becomes an agent of the corporations. There is finally Frank Chalmers, a Machiavellian evolutionary psychologist, whose schemes ultimately become so complex that he realises that he has no idea what his aims even are, or even if he has a personality at all. Only Phyllis survives the first novel.

These novels are each more ambiguous than the last. The cost of Utopia increases from one to the next. I have also presented them in chronological order of publication. One can hardly generalise from such a small sample, but I think it is nonetheless true that they are each historically typical. In the 1890s, as noted, many novels were written as fairly naive expositions of a good life that demanded a revolution in the organisation of social production. Though they hardly disappeared completely - one could name, perhaps, BF Skinner’s behaviourist Utopia Walden two, from the 1950s, or even Monique Wittig’s Les guérillères of 1969 - the utopian strand in western literature was decidedly ‘ambiguous’ at best by the time Le Guin composed The dispossessed. Robinson’s even grimmer picture sits oddly in the famous optimism of the 1990s, but then that optimism was precisely based on the idea that the dread spectre of utopianism was finally exorcised.

To return rudely to politics, our own Draft programme takes influence from the programmes being written more or less contemporaneously with Morris’s Utopia; the Erfurt Programme of the Social Democratic Party of Germany, or the founding programme of the French Workers Party. Yet, despite being a small thing compared to some books - particularly Robinson’s books! - it is very prolix, compared to those models. We are quite clear about why: the drafters of the Erfurt Programme were writing before the experience of Soviet and eastern European ‘socialism’. Those who take up the banner for communism today unavoidably take responsibility for the terrible results of the thing called ‘communism’ in the last century. We can set ourselves up as stupid tankies and explain that the purges were ‘good, actually’. We can try to wish the problem away, as left communists and more naive Trotskyists do - ‘Real communism has never been tried’. Or we can accept that ‘real communists’ failed to build real communism, that on the way they committed monstrous crimes, and learn from the experience, and try to communicate the lessons.

Dystopia

After all, the failure of those societies to become durable and worthy models has given us the inverted mirror image of the Utopia. There are capitalist, and fascist, and even neo-feudal dystopias out there. Yet the socialistic variants predominate - from Zamyatin’s We to Orwell’s Animal farm and 1984, and on and on. This is partly a matter of the prevailing ideological atmosphere in the capitalist world, of course, but partly written into the genre. The dystopia is parasitic upon the Utopia - it is always the Utopia gone wrong; the potential bad future of Anarres, where the moralism curdles into political tyranny and the fundamental morality becomes inverted. The classical dystopia does not only give us radical inegalitarianism, but gives us it in the clothes of egalitarianism. A morality of liberation becomes an apparatus of control.

Indeed, we have to mention that something like the Marxist taboo on utopianism spread into bourgeois thought, especially in the earlier stages of the cold war. It is no accident: many of the anti-communist intellectuals of that formative era were at the same time ex-communists or fellow travellers. For such people, Marxism in the end was not distinguished from utopianism; but also it had all too rosy a view of the consequences. The Marxist critique of Utopia, after all, was that - without the perspective of the class struggle - nothing would ultimately be achieved. The anti-communists raised the spectre not of failure, but of degeneration: all attempts to overthrow social hierarchy would invite only a worse tyranny. Dystopia was simply Utopia, 20 years later.

The ambiguous utopias are utopias after dystopia. Their concession - that, so to speak, Utopia ain’t what it used to be - may seem overly generous. What they buy with that is a meaningful narrative within the utopian frame. There is no more exposition in Le Guin than the average science fiction novel, probably less. What there is, instead, is a strong narrative, like all of them driven by escalating conflict, that does not take the form of the heroic individual against the suffocating society, but between individuals (novels are stories of individuals, after all) within the Utopia, and between the Utopia and its antagonist. The antagonists are clearly products of the social landscape, but intelligibly so: there is something to be fought over within the Utopia and against the pre-Utopia. It is a contested space: the achievement, or the mere possibility, of a new form of society does not exhaust contestation over the meaning or ends of that society.

I would argue that something similar befell fantasy literature starting in the 1990s. The mainline trend of Marxist SF studies - from Darko Suvin to Fredric Jameson - has always been a bit sniffy about fantasy, particularly after it eclipsed SF in commercial terms with the high fantasy boom of the 1980s. Even Jameson must concede, however, that the “world-building” of the fantasy author is at least related to the utopian imagination, perhaps more closely than the technological novum of classic SF that forms the core of Suvin’s theory.

The pulp, Tolkienesque, high-fantasy novel is typically a reactionary Utopia. You could think of, say, Robert Jordan’s Wheel of time books, with their incredibly detailed gender roles and cyclical battles between eternal principles of good and evil. The end of the cold war changed things, however. George RR Martin published A game of thrones and its sequels; the horror tinged ‘New Weird’ movement arose; and, in their wake, the centre of gravity of the genre shifted. History re-entered the picture: while Tolkien or Jordan produced various kinds of allegories of Christian eschatology, Martin and his epigones produced allegories largely of the bloody birth of capitalist modernity. Just as readers of the ambiguous Utopia could no longer credit cheerfully encyclopaedic accounts of societies of perfect happiness, even minimally sophisticated readers of fantasy no longer believed in the inherent nobility of royal bloodlines and the metaphysical division of the universe into good and evil.

The revisionist or ambiguous Utopia, then, is always unfinished - which is its answer to the anti-Utopians. It is not a new answer: that, after all, was the lesson of Marx’s and Engels’ critiques in the first place. All societies, liberated or tyrannical, real or fictional, emerge on the stage of human history, at some particular moment. To stretch the metaphor, their appearance immediately upends the set dressing. The stage is no longer as it was; new problems replace the old. The utopian impulse plays a particular role here: it directs us to what is out of reach, for now, to the need for further transformation, further revolution. It is opposed to the mere vulgar ‘realism’ exemplified by Robinson’s Frank Chalmers, which has a plausible but ultimately false ‘this-sidedness’ to it; addressed ‘realistically’ to a social reality at war with itself, which is therefore incapable of consistent representation in its own terms, it can terminate only in nihilism. It is precisely these contradictions that make Utopia real, even before it is achieved.

This is quite true whether our Utopia is of the Morrisian stripe - one that sees the liberated future as a return to some more fundamental human nature, no longer disfigured by the ugliness of exploitation - or it is a technological Utopia of idleness and abundance, as in the ‘Culture’ of Iain M Banks’s novels, or for that matter the later Star trek series. From my choices of exemplary texts, it should be clear that I am, for what it is worth, on ‘team Morris’ nowadays. For all the horrors of work under capitalism, I agree with him that it would be bad for a society to run out of useful things for people to actually do. I think there is such a thing as human nature, whether it is to be conceived in narrowly evolutionary or speculative and teleological terms. Others disagree strongly, to the point of arguing for post-human forms of Utopia. The dispute can be elaborated and better framed by argument, but not settled by it: that must wait, in the end, for revolution.

Where, then, does it fit into the Marxist political project proper? I leave aside the aesthetic dimension here, as I more or less have all along. News from nowhere is a charming pastoral romance; the Mars books are intimidatingly accomplished works of hard SF that are nonetheless far more readable than the average sample of that genre; The dispossessed is one of the great books of 20th century English literature, full stop, and if you take nothing else away from this talk, take my instruction to read it without delay! That is all I have to say on this matter; instead we move, for the last time, to the political.

The struggle for socialism has, as we often crudely put it, objective and subjective dimensions - the circumstances not of our own making, the ‘we’ who make our own history within them. The achievement of Marxism is to think these things together, but the distinction is not thereby abolished. The arrangement of class forces, relations of production, political relations of domination frame all human action. But these forces and relations are themselves always contradictory; even if nothing of human life escaped them, there would be freedom in those contradictions.

Utopia is thus a form in which those contradictions are reified. It appears as that over against which the grinding ordinary reality of class society is posed. It may not, in fact, be fully thematised - even a very unconscious, naive struggle at least demands the instinct that things need not be like this, things might be otherwise, even if we have only known them to be like this. Thus reified, Utopia serves as a moral impulse. It forms the subject of struggle; the moral motive for drawing radically egalitarian rather than merely sectional or individual conclusions from the moral bankruptcy of life in class society.

Those conclusions are ultimately verified in practice, in the victories or defeats accumulated over the years by rival approaches - internationalist or nationalist, sexually egalitarian or ‘complementarian’, and so on. Yet the empirical proof is only circumstantial until we achieve our goal. In practice, our motives for placing ourselves at the service of the objectively necessary are moral, and derive from our refusal to pay the costs of the alternative - of exploitation and oppression of ourselves or others. We do not await proof, but seek to prove it ourselves. In the meantime, we have our ways of weighing up the probabilities, of orienting our moral sense, even if the way to that morality is blocked for the time being.

Which is to say, we have our utopias - may there be many more.

For all Communist University talks, go to the CU2024 playlist on the CPGB Youtube channel:

www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLQ_b1NcwJsXecXLWDjqR2FDUaQgf2icaG