18.04.2024

Two election tactics

The Bolsheviks are rightly famous for their armed street demonstrations and storming of the Winter Palace. But what they are less known for is their use of elections to the duma, the tsar’s toothless parliament. Jack Conrad puts the record straight

Russia had its unique features - that was to be expected. However, it also had features that were general. More, we can say that within Russia the contradictions of capitalism found their highest, sharpest, expression. Fortunately, based as they were on solid Marxist theory, the Bolsheviks were able to develop their strategy and tactics to match the promising, but always hugely challenging, conditions. It is here that we find the international significance of the Bolshevik experience - not least their use of parliamentary elections and parliament itself.

So what were the electoral politics of the Bolsheviks?1 To answer that we must first examine the forces and possibilities of the Russian Revolution.

What separated the Bolsheviks and Mensheviks was far more than the dispute over soft or hard membership criteria, which precipitated the 1903 split between these once united partisans of Iskra. The cleavage at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party - where Bolsheviks (majorityists) and Mensheviks (minorityists) came into existence - stemmed from what were implicit, latent, but profoundly different strategic conceptions.

Both of the RSDLP’s big factions agreed that what was required, and what was in the offing, was in essence, the same as England 1649, America 1776 and France 1789; ie, a bourgeois revolution. Do not forget, Russia was ruled by an autocratic tsar and a clique of nobles, priests and hangers-on. Capitalist development was still comparatively feeble and the working class consequently small.

Taking this as their starting point, with a seemingly faultless appeal to what was claimed to be Marxist orthodoxy, the Mensheviks argued that the working class had to support the bourgeoisie in carrying out its historic mission. The working class had to follow, encourage and if necessary push the bourgeoisie to make revolution against the tsarist autocracy. The working class should meanwhile build its trade unions and improve its economic conditions, but, above all, do nothing ‘adventurous’. That would scare off the bourgeoisie, would lessen the ‘sweep’ of the bourgeois revolution.

Once safely ensconced in power, the bourgeoisie would faithfully introduce a parliamentary system, the full set of democratic rights and, all in all, open the road to unrestricted capitalist development. In due course, this would help form a politically conscious working class social majority. Till then, thoughts of any kind of working class state power were decidedly off the agenda. In the words of the Mensheviks’ April-May 1905 conference resolution, unless “the revolution spread to the advanced countries of western Europe ... social democracy should aim not to seize power or to share it in a provisional government, but should remain a party of extreme revolutionary opposition”.2

The Bolsheviks considered such a strategy, stagist, lifeless, artificial, conservative, mechanical and ahistorical. In short, they disagreed. This was not revolutionary Marxism. The Russian bourgeoisie was a spineless creature, compared with their 17th and 18th century English, American and French counterparts.

These epigones, not least in the form of the Constitutional Democrats, were incapable of making a revolution of any sorts. That was not the case, however, with the working class and peasant majority. The narod had already moved into action according to their own interests. As they did, far from the Cadets rushing to put themselves at their head, they trailed behind and were soon to be found desperately looking for a rotten, counterrevolutionary deal with the tsarist authorities in the form of a constitutional monarchy.3 Perceptively, Lenin instantly denounced the newly formed Cadets as “monarchist” and therefore anti-democratic.4

What was immediately possible in Russia was something infinitely more valuable to the proletariat of Russia - and the world at large - than a weak, pale and probably transient parliamentary democracy. The working class could do much better than lift the counterrevolutionary bourgeoisie into power and then, for who knows how long, bide their time as the Menshevik’s “party of extreme revolutionary opposition”.

Objective circumstances in Russia made it possible for the working class to seize the banner of democracy and the initiative. With single-minded leadership, daring and imagination, the working class could win hegemony over the peasant masses and take the lead in overthrowing tsarism - replacing it with what the Bolsheviks called the ‘revolutionary democratic (majority) dictatorship (decisive rule) of the proletariat and peasantry’. Such was the Bolshevik strategy, first sketched out by Vladimir Lenin in early 1905 and later that year given a fully rounded treatment in his masterful pamphlet Two tactics of social democracy in the democratic revolution.5

Europe

If realised, the Bolshevik’s anti-tsarist democratic revolution would be a work in progress. Left in isolation in Russia, it would be impossible to sustain, but the aim was always for Russia to provide the spark that would ignite the whole of Europe. This was no longer the epoch of the rising bourgeoisie. The advanced capitalist countries were objectively ripe for socialism. And, with a socialist Europe, Russia, under proletarian hegemony, could proceed uninterruptedly - that is, without the need for a second revolution - to the tasks of socialism.

How did things turn out? Well, according to the Mensheviks themselves, things turned out much closer to the perspectives of the Bolsheviks than their own - and not only in the great year of 1917, but in 1905, the great dress rehearsal too. Long tottering on the precipice, tsarism nearly went down as a result of the disastrous 1904-05 war with Japan. Taking advantage of tsarism’s weakness, revolt erupted in Kingdom Poland, Finland and Georgia, street demonstrations and strikes gripped St Petersburg, Moscow and other big cities, peasants seized land and tools, and army and naval units mutinied.

Here was a profound revolutionary situation which mercilessly tested the theories, programmes and expectations of all working class parties, groups and factions. To their credit, in the words of leading Menshevik Yuri Larin, in 1905 the Mensheviks “acted like Bolsheviks”.6 Confronted with the reality of a cowering and servile bourgeoisie and the heroism and determination of the working class, the Mensheviks momentarily put aside their strategy and let themselves be swept along by the floodtide.

Revolutions must be resolved positively. If not, they are resolved negatively. Either revolution or counterrevolution will win the day. That is why the Bolsheviks were determined to take what possibilities there were for success in 1905 to their limit.

Of course, revolutions are not one-way affairs. Initiative and tactical manoeuvre are not the sole prerogative of the popular forces. Those above - even though split, confused and panicked by revolutionary developments they can never really understand - still have resources, finance and the experience necessary to offer well chosen sops. Hence, when Cossacks and the police failed to terrorise the masses into submission, Nicholas II issued his October manifesto, which granted some minimal civil rights and elections to a consultative duma or parliament (only those over 25 were to be given the vote and, of course, there was no thought of extending the franchise to include women).

How did the Bolsheviks respond? With the great bulk of advanced workers fully behind them, with utter conviction, with a refusal to be diverted from the real prize, the Bolsheviks called for an election boycott and, alongside that, preparations for an armed uprising.

The revolution reached its height in the last months of 1905, with mass political strikes, peasant revolts, soldiers and sailors sending delegates to the soviets, and the formation of armed units. However, with a peace deal signed with Japan and the liberal opposition vacillating, the tsarist authorities were ready for a ruthless clampdown. Leon Trotsky, chair of the St Petersburg soviet, was arrested on December 3, along with other members of its executive committee.

The centre of gravity briefly shifted to Moscow, where the Bolsheviks had a strong influence. They made the call for a political general strike, and for efforts to be made to transform it into armed insurrection. That is indeed what happened. With the active help of the city’s million-strong population, less than a thousand guerrillas were able to duck and dive between a string of symbolic street barricades and keep 10,000 troops at bay for nine splendid days.

Note, many of the tsar’s troops arrived directly from Manchuria and were therefore free of infection from revolutionary ideas. But, while there were other local attempts, no nationwide insurrection followed. Crucially, St Petersburg did not move. December’s action had to be called off by the Moscow soviet. The tsarist authorities took swift revenge: not only were there thousands of arrests, trials and sentences of internal exile, hundreds were unofficially executed and buried in unmarked graves.

The revolution was not broken, though the tide had substantially ebbed. A few months later, in March 1906, duma elections were held. The Bolsheviks and others on the left called for an active boycott. That did not mean the Bolsheviks were saying workers should adopt an anarchist-style abstention from political struggle. The boycott call, reluctantly accepted by Lenin, was to keep the possibility of a nationwide insurrection alive … and, as it turned out, the first duma only lasted till July 1906. Nicholas II had no liking for its liberal bourgeois-peasant majority and, as he could, dissolved it and announced new, even more restrictive, electoral laws.

There were good reasons to believe that not all was lost. Membership of both the Bolshevik and Menshevik factions continued to grow in leaps and bounds, and had already assumed mass proportions. Though the Socialist Revolutionary Party officially boycotted the elections, 34 SRs were elected. So too were 18 Mensheviks. Interestingly, Lenin reached out to influence and help them.

Basically his approach was to win the social democrat deputies to champion the radical demands of the peasantry, not least land redistribution, thereby they would expose the liberal bourgeois Cadets as false friends of the people. A particular target of his polemics was Peter Struve, now a Cadet, but once a sort of Marxist (he wrote the RSDLP’s founding manifesto in 1898). Of course, the theoreticians of Menshevism - Pavel Axelrod, Fyodor Dan and Alexander Potresov - had other ideas. They instinctively cleaved to the liberal bourgeoisie. The Cadets, after all, were the very people they looked to as the historically predetermined leadership of the revolution.

Looking back, in his famous pamphlet, Leftwing communism (1920), we find the following assessment:

The boycott of the Witte duma was … a mistake, although a small and easily remediable one … What applies to individuals applies - with necessary modifications - to politics and parties. Not he is wise who makes no mistakes. There are no such men nor can there be. He is wise who makes not very serious mistakes and who knows how to correct them easily and quickly.7

Yes, the boycott was a mistake. Nevertheless it was, as Lenin said, a small one - small because it was quickly and imaginatively rectified.

Within the year the boycott gave way to full, effective and very impressive intervention in tsarist elections. Bolshevik participation in what was a travesty even of what the bourgeoisie calls ‘democracy’ did not, however, mean an end to the struggle between themselves and the Mensheviks. In fact, divisions continued, even as the two factions came together in the RSDLP’s Unity Congress of April-May 1906: the Bolsheviks and Mensheviks constituted respectively the left and right wings.

Given the underlying strategic differences, it is no surprise that, when it came to duma elections and duma tactics, there were two distinct approaches. Not a case of the ‘streets’ versus the ‘ballot box’ - a stupidity we routinely encounter in the pages of Socialist Worker.8 No, the difference between the Mensheviks and Bolsheviks was about opportunist parliamentarism versus revolutionary parliamentarism.

Let us begin by outlining the main parties and party groupings, from right to left. On the extreme right there was the bloc of parties - the League of the Russian People, the monarchists, the Council of the United Nobility. These were counterrevolutionary, tsarist parties: parties that wanted to maintain the status quo; parties of the landlords and clergy, which organised and paid for anti-Jewish pogroms by lumpen gangs of Black Hundreds (a generic term for their extra-legal armed forces). To the left of these parties of the Black Hundreds stood the Octobrists, a deeply reactionary bourgeois party. But the main party of the bourgeoisie, as already mentioned, were the Cadets.

The Cadets quickly settled for the idea of a constitutional monarchy, but to realise that thoroughly moderate aim these liberals were prepared to threaten Nicholas II with revolution. What they were not prepared to do, though, was to make revolution themselves. Revolution, made by workers and peasants, the narod, was seen as a danger that the tsar’s stubborn insistence on upholding the ancien régime by arrogantly proclaiming Russia a ‘constitutional autocracy’ only brought nearer. The Cadets were themselves horrified by the prospect of revolution. Definitely something to be avoided. Only an energetic programme of liberal reform could do that, they slavishly pleaded.

Attempts by the Cadets to gain sway over the peasantry therefore had to be fought and their hypocritical, fake democracy uncompromisingly exposed. Lenin wrote:

To apply the term ‘democratic’ to a monarchist party, to a party which accepts an upper chamber, proposed repressive laws against public meetings and the press and deleted from the reply to the address from the throne the demand for direct and equal suffrage by secret ballot, to a party which opposed the formation of land committees elected by the whole people - means deceiving the people. This is a very strong expression, but it is just.9

It almost goes without saying that those who did “apply the term ‘democratic’” to the Cadets were none other than the Mensheviks. That is why Menshevik leaders made endless proposals for joint action with the Cadets and an equal number of excuses for their refusals and acts of cowardice.

Anyway, to the left of the Cadets stood the Trudovik grouping, which claimed to be for socialism and was supported by wide sections of the peasant masses. The Trudoviks included an assorted collection of non-party people, but in effect served as an outstation for the Socialist Revolutionary Party and the Popular Socialist Party: the latter being closer in spirit to the Cadets, closer in spirit to the bourgeoisie than the Socialist Revolutionaries, the more genuine revolutionary organisation.

It was in relationship to these groupings, parties and the classes they varyingly represented that the revolutionary and opportunist wings of the RSDLP argued, negotiated and positioned themselves. There were two main prongs to the Menshevik approach. First, the necessity of keeping out the Black Hundreds; they were the biggest evil. Second, as just mentioned, making the liberal bourgeoisie - ie, the Cadets - fight.

The Bolsheviks had a very different approach. Their view of politics was not determined by who was more evil and who was less evil. No, they took as their starting point the needs of the working class and who was and who was not revolutionary. Neither the landlords nor the bourgeoisie were revolutionary classes. But within strict historic limits the peasants were. Hence, while the Bolsheviks wanted to beat both the Black Hundreds and the Cadets, they wanted to get to, appeal to, win over, the peasants - and not by engaging with the Trudoviks. Their ‘three pillars’ programmatically were: a democratic republic, confiscation of the landed estates and an eight-hour working day.

While the Mensheviks had gone along with general strikes, soviets and insurrection in 1905, as the revolutionary tide retreated ever further during the course of 1906, they returned to type. They clutched at their old conception of the bourgeois-led character of the Russian bourgeois revolution: surely a case of keeping hold of something you know, for fear of finding something worse. The announcement by Nicholas II, on July 21 1906, that he was going to dissolve the first, Witte, duma even saw the Mensheviks effectively accepting tsarism’s constitutional framework.

The Mensheviks issued the slogan, “A duma with real powers”, and called for a general strike and demonstrations to save what was always a sop. For the Bolsheviks, defence of any sort of tsarist duma was a complete diversion. They mocked the Mensheviks’ duma cretinism, and went to the factories and working class districts agitating against a general strike and demonstrations in defence of the indefensible.

Workers were urged not to take precipitate action. With the revolution on the defensive, but still not defeated, with the December action still fresh in minds, the Bolsheviks argued that what was needed was a constituent assembly born of revolution, not a tsarist “duma with full powers”. Instead of placing hopes on an instant general strike and banking on the Cadets, the Bolsheviks looked to “enlighten and educate” the masses by participating in the tsar’s new elections.

Indeed their campaign proved pretty successful. Among the 65 social democrats elected were a solid bloc of 18 Bolshevik deputies. Most were rank-and-file workers with little in the way of higher learning. Lenin took to giving close advice and leadership. He wrote many of their formal speeches. Inevitably, however, the comrades made political “mistakes” - even “departed from the political line of the party” - but they alone were not to blame and with the help of the whole party things could be put onto a “different basis”.10 The idea of democratic centralism began to be used. Lenin certainly had no wish for the parliamentary fraction to in effect become ‘the party’ (as with the Parliamentary Labour Party in Britain and some other countries in western Europe). That would be an abomination.

Disagreements

Of course, not all Bolsheviks agreed with this shift in tactics. Alexander Bogdanov, Lenin’s lieutenant in 1905, became leader of the otzovist [‘recallist’] trend, which pictured the “Bolshevik centre” surrendering “every Bolshevik position, one after another”.11 What such criticism amounted to, though, was the liquidation of legal party work, focused as it was, on the demand to recall RSDLP deputies from what was now a bourgeois-Black Hundreds duma. Understandably many party militants recoiled in disgust. Another Bolshevik variety of boycottism was the ‘ultimatists’, who wanted to break off relations with duma deputies unless they agreed to abide by an ultimatum stipulating that they obey all the decisions of the central committee.

For a short while, Lenin found himself in a minority. He even threatened to “leave the [Bolshevik] faction immediately” if the recallist line prevailed.12 There was a whole series of open polemical exchanges in the Bolshevik press. True, liberals and petty bourgeois socialists mocked the Bolsheviks for ‘washing their dirty linen in public’. Yet without such frankness, without such transparency, the broad mass of the working class could never be politically trained, and without that the idea of a popular revolution was a complete non-starter.

Lenin’s demolition job on Bogdanov’s idealist philosophy, his insistence on combining illegal with legal work and the promise of emulating German social democracy, which had learnt how to survive the anti-socialist laws and exploit elections to the Reichstag to brilliant effect, won the day. An enlarged conference of the editorial board of Proletary, the Bolshevik’s paper - held in Paris over June 21-30 1909 - saw a resolution condemning both otzovism and ultimatism overwhelmingly agreed. Otzovism and ultimatism, it stated,

expresses the ideology of political indifference on the one hand and anarchistic vagaries on the other. For all its revolutionary phraseology, the theory of otzovism and ultimatism in practice represents, to a considerable extent, the reverse side of constitutional illusions .... All the attempts made so far by otzovtism and ultimatism to lay down principles inevitably led to denial of the fundamentals of revolutionary Marxism. The tactics proposed by them inevitably lead to a complete break with the tactics of the left wing of international social democracy as applied to contemporary Russian conditions, and result in anarchist deviations …. Bolshevism, as a definite trend within the RSDLP has nothing in common with otzovtism or with ultimatism ... the Bolshevik wing of the party must resolutely combat these deviations from the path of revolutionary Marxism.13

Bogdanov and his co-thinkers were branded left liquidators and formally expelled from the Bolshevik faction (not the party). But actually he had already walked. Soon his Vperyod group were preaching the standard ‘non-sectarian’ banalities, promoting the centrality of didactic education and proletarian culture, joining worthless diplomatic unity schemes - before spiralling off into self-confessed political irrelevance. Bogdanov abandoned revolutionary activity in 1912 and returned to Russia in 1914, following the tsar’s amnesty marking the tricentenary of the Romanov dynasty.

Blocs

Let us turn to the January-March 1907 election campaign for the second duma. This is important, because it basically characterised the Bolshevik’s approach right up to November 1917, when, under conditions of soviet power, they presided over elections to the Constituent Assembly.14

The first thing that strikes one is the fundamentally different attitude towards alliances. The Mensheviks proposed an electoral bloc with the Cadets - if the party did not do that, the masses would never forgive them. Nicholas II had weighted the whole electoral system heavily in favour of the propertied classes. So, when it came to forming a duma majority, it was going to be either the Cadets or a bloc of Black Hundreds. Naturally, the Mensheviks had no hesitation about stating their preference between these two evils.

Readers will not be surprised to learn that the Bolsheviks disagreed. They insisted that working class independence was the main question. Our “main task is to develop the class consciousness and independent class organisation of the proletariat”, wrote Lenin. Only that class can lead “a victorious bourgeois-democratic revolution. Therefore, class independence throughout the election and duma campaigns is our most important general task”.15

The Bolsheviks did not apply this approach only to the Cadets, but the Trudoviks, Popular Socialists and the Socialist Revolutionary Party too. Lenin insisted:

The argument about the proletarian-peasant character of our revolution does not entitle us to conclude that we must enter into agreements with this or that democratic peasant party at this or that stage of the elections to the second duma. It is not even a sufficient argument for limiting the class independence of the proletariat during the elections, let alone for renouncing this independence.16

Hence, in the cities, where the working class population was concentrated, Lenin said that the RSDLP

must never, except in case of extreme necessity, refrain from putting up absolutely independent social democratic candidates. And there is no such urgent necessity. A few Cadets or Trudoviks more or less (especially of the Popular Socialist type!) are of no serious political importance, for the duma itself can, at best, play only a subsidiary, secondary role.17

Bolshevik stress on working class political independence and presenting independent candidates to the working class clearly stemmed from core principle. That is why in 1912 they refused to countenance even a bloc of opportunist and revolutionary working class parties. Here is how one of the successful Bolshevik candidates wrote about it:

The Bolsheviks thought it necessary to put up candidates in the workers’ curia and would not tolerate any agreements with other parties or groups. including the Menshevik-liquidators. They also considered it necessary to put up candidates in the so-called ‘second curia of city electors’ ... and in the elections in the villages, because of the great agitational attitude of the campaign.18

Putting forward independent party candidates, refusing to enter blocs, did not mean the Bolsheviks were oblivious to the advantages of ‘partial agreements’. To appreciate what was meant by this it is necessary to say something about the tsar’s convoluted electoral laws.

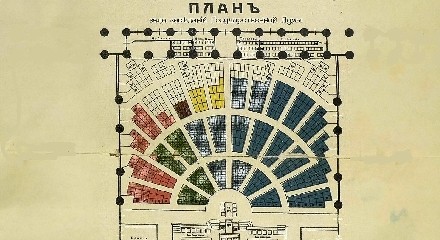

Curia

The tsar’s duma was not elected directly. Nicholas II thought it would be far safer to divide the population into six curias or ‘estates’: landowners, city habitats, peasants, workers, Cossacks, and non-Slavic people. Each curia had its own weighting: eg, landlords - one elector per 2,000; peasants - one elector per 4,000; workers - one elector per 30,000.19 The electors eventually determined the deputies allotted to each curia.

In the distribution of seats by these intermediate elected ‘electors’, the Bolsheviks considered “partial agreements” perfectly permissible.20 Lenin used the following hypothetical example to illustrate how they would work. If in the countryside there were 100 electors and “49 are Black Hundreds, 40 are Cadets and 11 are social democrats”, then a “partial agreement between the social democrats and the Cadets is necessary in order to secure the election in full of a joint list of duma candidates, on the basis, of course, of a proportional distribution of duma seats according to the number of electors.”21

Hence, in this case, if there were five duma seats up for grabs, the Bolsheviks saw every reason to completely exclude the Black Hundreds - that is, as long as the Cadets were prepared to give them, the social democrats, one of the duma seats. This would be facilitated by making it clear to the masses what arrangements were on offer and being negotiated.

Who were the Cadet electors going to make a deal with? With the revolutionary social democrats or the Black Hundred pogromists? In this way the RSDLP could force the 40 Cadets to do a deal with the 11 social democrats and leave the Black Hundreds out in the cold. Naturally, if the balance was different, if it was more favourable, the same treatment would be meted out to the Cadets - if, say, there was a possibility of doing a deal with electors inclined to support the SRs; and, in turn, if the arithmetic was favourable, every effort would be made to split away genuine revolutionary elements from them.

Of course, not least in the cities, duma seats were entirely secondary. Here the

importance of the elections is not at all determined by the number of deputies to be sent into the duma, but by the opportunities for the social democrats to address the widest and most concentrated sections of the population, which are the most social democratic in virtue of their whole position.22

In the cities there should be

no agreements whatsoever at the lower stage, when agitation is carried on among the masses; at the higher stages all efforts must be directed towards defeating the Cadets during the distribution of seats by means of a partial agreement between the social democrats and Trudoviks, and towards defeating the Popular Socialists by means of a partial agreement between the social democrats and the Socialist Revolutionaries.23

As was bound to be the case, Lenin and the Bolsheviks were confronted with the ‘lesser of two evils theory’ - a theory that has certainly been used against us, and is effectively meant to outlaw any independent communist activity in the electoral field: eg, ‘Vote Labour, keep the Tories put’. This rotten theory was, unsurprisingly, the main argument the Cadets used to recommend themselves. As Lenin noted,

the whole of the Cadets’ election campaign is directed to frightening the masses with the Black Hundred danger and the danger from the extreme-left parties, to adapting themselves to the philistinism, cowardice and flabbiness of the petty bourgeois and to persuading them that the Cadets are the safest, the most modest, the most moderate and the most well behaved of people.24

In other words, the Cadets went to the electorate as the lesser evil, and said: ‘Vote for tinkering reforms, vote for safety’. They threatened the middle classes with what they thought were the greater evils, the danger, on the one hand, of letting in the Black Hundred pogromists and, on the other, Lenin and those terrible people who caused all the bloodshed and disruption in Moscow in the dark days of December 1905.

Those who believed the Cadets to be progressive were in their turn forced to adapt to, and even adopt, their method. The Mensheviks did not want the working class to do anything that might upset the Cadets. Nothing must be done that might push them towards the camp of the biggest evil, the Black Hundreds. To encourage the Cadets along the road that led to the bourgeois revolution, they wanted to support them with offers of joint lists, blocs and alliances.

It was either that, said the Mensheviks, or the Black Hundreds. Here is how Lenin summarised the Menshevik approach:

Let the social democrats criticise the Cadets before the masses as much as they like, but let them add: yet they are better than the Black Hundreds, and therefore we have agreed upon a joint list.

And here is how Lenin countered it:

The arguments against are as follows: a joint list would be in crying contradiction to the whole independent class policy of the Social Democratic Party. By recommending a joint list of Cadets and social democrats to the masses, we would be bound to cause hopeless confusion of class and political divisions. We would undermine the principles and the general revolutionary significance of our campaign for the sake of gaining a seat in the duma for a liberal! We would be subordinating class policy to parliamentarism instead of subordinating parliamentarism to class policy. We would deprive ourselves of the opportunity to gain an estimate of our forces. We would lose what is lasting and durable in all elections - the development of the class consciousness and solidarity of the socialist proletariat. We would gain what is transient, relative and untrue - superiority of the Cadet over the Octoberist.25

Contempt

Lenin was not frightened by Menshevik warnings that independent social democratic electoral work would let in the Black Hundreds. As we can see, he treated such arguments with the contempt they deserve:

The ... flaw in this stock argument is that it means that the social democrats tacitly surrender hegemony in the democratic struggle to the Cadets. In the event of a split vote that secures the victory of a Black Hundred, why should we be blamed for not having voted for the Cadet, and not the Cadets for not having voted for us?

‘We are in a minority,’ answer the Mensheviks, in a spirit of Christian humility. ‘The Cadets are more numerous. You cannot expect the Cadets to declare themselves revolutionaries.’

Yes! But that is no reason why social democrats should declare themselves Cadets. The social democrats have not had, and could not have had, a majority over the bourgeois democrats anywhere in the world where the outcome of the bourgeois revolution was indecisive. But everywhere, in all countries, the first independent entry of the social democrats in an election campaign has been met by the howling and barking of the liberals, accusing the socialists of wanting to let the Black Hundreds in.

We are therefore quite undisturbed by the usual Menshevik cries that the Bolsheviks are letting the Black Hundreds in. All liberals have shouted this to all socialists. By refusing to fight the Cadets you are leaving under the ideological influence of the Cadets masses of proletarians and semi-proletarians who are capable of following the lead of the social democrats. Now or later, unless you cease to be socialists, you will have to fight independently. In spite of the Black Hundred danger. And it is easier and more necessary to take the right step now than it will be later on. In the elections to the third duma ... you will be still more entangled in unnatural relations with the betrayers of the revolution. But the real Black Hundred danger, we repeat, lies not in the Black Hundreds obtaining seats in the duma, but in pogroms and military courts: and you are making it more difficult for the people to fight this real danger by putting Cadet blinkers on their eyes.26

In a nutshell, the differences between the Bolsheviks and Mensheviks amounted to the fact that, where the Bolsheviks wanted “complete independence in the election campaign”, the Mensheviks, by contrast, wanted a solid Cadet duma “with a large number of social democrats elected as semi-Cadets!”. Where the Mensheviks were prepared to sacrifice their political independence for the electoral defeat of the greater evil - the Black Hundreds - the Bolsheviks fought and worked for revolution.

In pursuit of this it was better to have a duma consisting of “200 Black Hundreds, 280 Cadets and 20 social democrats” independent from the Cadets, than a duma consisting of “400 Cadets and 100 social democrats” elected as semi-Cadets. And Lenin defiantly declared: “We prefer the first type, and we think it is childish to imagine that the elimination of the Black Hundreds from the duma means the elimination of the Black Hundred danger.”27

To back up their position the Bolshevik publishing house produced Russian editions of works by their German comrades, Karl Kautsky and Wilhelm Liebknecht. For instance, in The driving forces of the Russian Revolution and its prospects, the highly influential Kautsky was full of praise for the 1905 revolution and the barricade tactics of the Bolsheviks, and dismissive of the revolutionary potential of the Russian bourgeois.28 Wonderful anti-Menshevik ammunition, and used to good effect. Liebknecht’s pamphlet, No compromises, no electoral agreements, was if anything even more useful.

We can get a taste of what it had to say from the preface Lenin wrote, which we might say turned the ‘lesser of two evils theory’ onto its feet. Here is a short excerpt:

The class consciousness of the masses is not corrupted by violence and draconian laws: it is corrupted by the false friends of the workers, the liberal bourgeois, who divert the masses from the real struggle with empty phrases about a struggle. Our Mensheviks and Plekhanov fail to understand that the fight against the Cadets is a fight to free the minds of the working masses from false Cadet ideas and prejudices about combining popular freedom with the old regime.

Liebknecht laid so much emphasis on the point that false friends are more dangerous than open enemies that he said: “The introduction of a new anti-socialist law would be a lesser evil than the obscuring of class antagonisms and party boundary lines by electoral agreements.”

Translate this sentence of Liebknecht’s into terms of Russian politics at the end of 1906: ‘A Black Hundred duma would be a lesser evil than the obscuring of class antagonisms and party boundary lines by electoral agreements with the Cadets’ ... Only bad social democrats can make light of the harm done to the working masses by the liberal betrayers of the cause of the people’s liberty who ingratiate themselves with them by means of electoral agreements.29

The Bolshevik approach won the day at the RSDLP’s May 13-June 1 1907 London congress. Besides pushing the idea of a ‘broad workers’ party’, the Mensheviks, who lost their short-lived central committee majority, had urged the 338 delegates to go for a ‘lesser evil’ policy, whereby social democrat deputies in the duma would support a Cadet - even a ‘left’ Octobrist candidate - for speaker.

Relations with the Bolsheviks further soured, as the increasingly fragmented Mensheviks careered off to the right. Whereas the Bolsheviks had dealt decisively with their left liquidators, those who effectively wanted to put an end to legal duma activities, the Mensheviks were characterised by right liquidationism. They wanted to put an end to illegal activities such as ‘expropriations’ and the whole underground apparatus. Their model was something like the British Labour Party and the promise that this would be acceptable to Nicholas II (ie, total capitulation before tsarism).

Things came to a head with the January 5-17 1912 Prague conference, when the Menshevik liquidators were deemed to have put themselves outside the party (incidentally, the conference was chaired by a pro-party Menshevik). Breaking with the Menshevik liquidators and seeking a rapprochement with Georgi Plekhanov’s pro-party Mensheviks was a bold, daring move and, though it largely failed, it did set the stage for the Bolsheviks’ September-October 1912 duma election campaign.

The fourth duma saw them win all six of the deputies allocated to the workers’ curia. True, there were seven other social democrats (six Mensheviks were elected as part of a bloc with liberals and petty bourgeois democrats, and one other was elected from Warsaw with help from the Bund). Either way, it was a drop in the ocean of a 422-seat duma completely dominated by liberals and rightists. But the exact make-up of the duma was an entirely third-rate issue.

What really mattered was that the Bolsheviks were the indisputable majority, when it came to the mass of the working class. An entirely first-rate issue.

-

The best account by far of the Bolsheviks’ approach to parliamentary elections is August H Nimtz’s two-volume Lenin’s electoral strategy New York NY 2014.↩︎

-

Quoted in N Harding (ed) Marxism in Russia: key document 1879-1906 Cambridge 1983, p314.↩︎

-

I am not aware of any worthwhile study of the Cadets as such, but, in terms of a biography, take a look at Stephen Williams’s account of one of their most prominent leaders, Vasily Maklakov. See SF Williams The reformer: how one reformer fought to prevent the Russian Revolution New York NY 2017.↩︎

-

VI Lenin CW Vol 8 Moscow 1977, pp488‑89.↩︎

-

See VI Lenin CW Vol 9, Moscow 1977, pp15-140.↩︎

-

VI Lenin CW Vol 11 Moscow 1977, p363.↩︎

-

VI Lenin, CW Vol 31, 1977, pp35-36.↩︎

-

For a recent manifestation of this anarcho-economism we have Charlie Kimber, Socialist Worker editor, writing against giving any support for George Galloway: “We need a left that fights for Palestine - and also takes up other issues. And the most important direction for those who have marched over Gaza is still in the streets, building the movement, not the ballot box” (Socialist Worker April 10 2024).↩︎

-

VI Lenin CW Vol 31, Moscow 1977, p311.↩︎

-

VI Lenin CW Vol 15 Moscow 1977, p352.↩︎

-

Quoted in RV Daniels (ed) A documentary history of communism Vol 1, London 1985, p45.↩︎

-

N Krupskaya Memories of Lenin Vol 2, London nd, p24.↩︎

-

VI Lenin CW Vol 15 Moscow 1977, pp444-46.↩︎

-

Elections to the Constituent Assembly were constantly put off by a fearful Provisional Government after the February Revolution. The election was not held until after the October Revolution and, although the Bolsheviks participated - coming second behind the (now split) Socialist Revolutionary Party - the assembly was forcibly dissolved in January 1918 on the orders of the Bolshevik-Left SR coalition government, which derived its moral authority from its commanding majority in the workers’, peasants’ and soldiers’ soviets.↩︎

-

VI Lenin CW Vol 11 Moscow 1977, p279.↩︎

-

Ibid p280.↩︎

-

Ibid p286.↩︎

-

A Badayev The Bolsheviks in the tsarist duma London 1932, p9.↩︎

-

VI Lenin CW Vol 11 Moscow 1977, p289.↩︎

-

Ibid p291.↩︎

-

Ibid p296.↩︎

-

Ibid p283.↩︎

-

Ibid p415.↩︎

-

Ibid p285.↩︎

-

Ibid p314-15.↩︎

-

Ibid p315-16.↩︎

-

N Harding (ed) Marxism in Russia: key documents 1879-1906 Cambridge 1983, pp352, 372.↩︎

-

VI Lenin CW Vol 11 Moscow 1977, p403.↩︎