22.06.2023

Death of a true believer

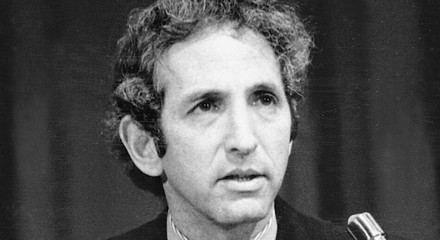

He exposed official lies, escaped the clutches of Richard Nixon’s goons and fought hard for pacifism for the rest of his life. Paul Demarty remembers Daniel Ellsberg

It is strange, writing two articles in a row which are both obituaries; comparisons inevitably present themselves.

Both Ted Kaczynski and Daniel Ellsberg, who died last week of pancreatic cancer, were men of deep political conviction - conviction that guided their entire lives. They could perhaps both be credited with courage of some sort; and indeed the period of their ‘activism’, so to speak, was similar - roughly the 1970s onwards. Beyond that, the comparison breaks down. Kaczynski, as we noted last week (‘Death and the cabin’, June 15), was motivated by a jumble of alienated impulses, embraced a terrorism of despair, and campaigned in the end against an unkillable abstraction: the technological society (indeed the Promethean impulse per se). His failure was ordained, and his arrest a submission to the inevitable.

Ellsberg was, in stages, awakened to the horror in which he was an actor - of the perceived necessity to contemplate the near extinction of the human race to stop this or that ex-colony from falling into the Soviet camp. He overcame despair to betray the deepest workings of the American state. His activism, from then on, was always a public affair, and always in the service of a hard-won and deeply principled pacifism. His support of similar whistleblowers down the years is perhaps unsurprising, but disclosed an admirable consistency. I am not a pacifist, and the Weekly Worker is not a pacifist publication, but history will remember him as one of the good ones.

Game theory

Ellsberg was born in Chicago - to bourgeois parents of Jewish background, but Protestant faith. He excelled academically, graduating from Harvard with a major in economics, before joining the marines as a commissioned officer. At the end of that process, he had exactly the combination of credentials to be ripe for entry into the military-industrial complex, and found himself working for the RAND Corporation, the think-tank that most epitomises that complex. Assembled out of various boffins who had been working for the state during World War II, it rapidly became extremely influential and specialised - especially after the USSR detonated a nuclear bomb - in planning for conflict between powers with unprecedented destructive weaponry at their disposal.

It was at RAND that, in 1950, mathematician and economist John Nash formulated the basic tenets of ‘game theory’ - essentially a framework for creating thought experiments about the behaviour of adversarial actors with imperfect information. As the cold war heightened, with the partition of Germany becoming effectively permanent and ‘hot’ war between the US and various Soviet allies breaking out in Korea, game theory became a major building block of US nuclear strategy, giving us the cheery doctrine of mutual assured destruction (MAD) in due course. (RAND’s intellectual peregrinations are the target of the chilling satire of Dr Strangelove; Nash’s later struggles with schizophrenia, on the other hand, were portrayed in the gloopy Hollywood biopic, A beautiful mind).

Nuclear planning was Ellsberg’s speciality in his early days at RAND. He made his own contribution to the game theory field with the insight that people favour decisions where the risks are known rather than ambiguous, even when they are aware that alternative courses of action are likely to have better outcomes - an argument that has generated no end of literature since. Yet, to hear him tell it, he was already uneasy about the scenarios he was actually working out. MAD seemed to live up to its acronym.

From there, he was seconded to the defence department by Robert McNamara, who was overseeing the rapid expansion of the US’s involvement in Vietnam and proposed to make a breakthrough by creating the ultimate brains’ trust. Bright RAND staffers like Ellsberg were key members of ‘the best and the brightest’, and they duly placed American conduct in the war under close examination. The conclusion they came to, more and more, was that the war was unwinnable without a drastic increase in resources being ploughed into it. After 1967, by which time Ellsberg was back at RAND, these concerns were producing a significant documentary record; the government of Lyndon Johnson, however, repeatedly misled Congress about the progress being made.

Change of heart

Ellsberg’s conscience tugged at him ever more. He started attending anti-war demonstrations. In 1969, he finally committed himself to the cause, and did the one thing he - and, within the movement, almost only he - could do. He duplicated all those documents, with the assistance of a colleague, making several copies. After failing to interest several senators in exposing the material (they would be protected from prosecution), he finally succeeded, in 1971, in interesting The New York Times in the material, which they began publishing. Its right to do so was upheld in a landmark Supreme Court case.

The US government had, in the meantime, changed. In some respects, Richard Nixon was more amenable to the message of the Pentagon Papers - that Vietnam was a disaster, and the US needed a more or less dignified off-ramp. (That ‘off-ramp’ went through a genocidal bombing campaign in Cambodia, of course, but you can’t have it all.) Yet this paranoid thug would not let such an insult pass. Thus there came to be the notorious ‘White House plumbers’, who sought to fix the various leaks in the state core by underhand methods. They illegally bugged Ellsberg, and even burgled his therapist’s office, hoping to find something to discredit him. In the meantime, Ellsberg handed himself in to police, and awaited trial under the grotesque Espionage Act.

By the terms of the act, the presiding judge forbade the defence from addressing the jury to explain Ellsberg’s motives (a proscription that was scandalous at the time, but has become routine in such cases). Yet the steady drip of revelations about the activity of the ‘plumbers’ made the prosecution untenable. Nixon’s thuggery and crudity - and arguably the unpopularity of his policy of detente in sections of the deep state - allowed Ellsberg to get away with it. From then on, Ellsberg was committed to the peace movement: he could perhaps be compared to John Newton - the English slave trader turned abolitionist.

That brings us to his consistent support of whistleblowers and journalists who expose state secrets - among them Julian Assange, Chelsea Manning, Edward Snowden and many more. It was possible, perhaps, in the mid-1970s to view Ellsberg’s trial optimistically as a turning point - followed, as it was, by the Watergate fiasco and then the revelations of the Church committee: the secret state was a wounded beast and, if the rightwing theories about Nixon’s enemies in the security apparatus have any merit, it was at least in part a self-inflicted injury. Squabbles between factions of the security state created the conditions for an idealist like Ellsberg, or a crusading senator like Frank Church, to give them a bloody nose.

Back in control

Bureaucratic turf wars and other maladies have hardly disappeared from the security state, of course. But the evidence of the treatment of Ellsberg’s inheritors is surely that, in this respect at least, they are in quite as strong a position as they were at the beginning of the 1970s. Julian Assange languishes at Belmarsh - surely to be extradited to face charges under the same draconian Espionage Act hurled at Ellsberg. The same fate would surely have awaited Edward Snowden, had he not been shielded to some extent by the Russian state; and if the US does succeed in a regime decapitation in Moscow, his safety is hardly assured.

Assange and Snowden were at least politically motivated, by a common right-libertarianism in essence; the same could be said for the socialist and communist activists who were, in reality, the target of the legislation in the first place. But, by targeting Jack Teixeira - who leaked the so-called ‘Discord files’ with apparently no more noble or maleficent motive in mind than impressing some idiot gamer children in a private Discord server - this grotesque law reaches its ultimate absurdity.

As for the pacifism - we could hardly call our age terribly pacifistic. The US did withdraw, eventually, from Vietnam, but wasted no time in going on the offensive against a decrepit Soviet enemy, manufacturing al-Qa’eda out of nothing in the process. Since then, we have seen the reduction of Somalia to a failed state, imperfectly frozen conflicts in the Balkans, the bloody catastrophes of Afghanistan and Iraq, state failure and near state failure in Syria and Libya, thanks to US action, and, finally, the conversion of relentless provocations on the borders of Russia into open, gruesomely attritional warfare.

Few indeed have been the moments, amidst all this bloodshed, when the mainstream media outlets that bought Ellsberg’s photocopies showed anything other than complete compliance with the imperatives of state-department orthodoxy. Today, The New York Times and the like write oh-so-solemn open letters about the dangers posed to free speech by the Assange case - but only now that his prosecution is essentially inevitable have they bothered. When there was any hope of protecting him, such outlets had nothing to offer than relentless slander and laughable dishonesty about his case.

This rather bleak outlook must, in the end, enter into our assessment of Ellsberg’s legacy. There is a certain idea, implicit in all his activity, that if people only ‘knew’, then the hideous crimes of the imperial state would become untenable. That turns out not to be the case; for knowledge in its political form is always doubled - there is the knowledge of the facts of the matter and the knowledge of what can, or must, be done about them. The latter inevitably frames the former. The instinct many people have of their powerlessness in the face of impenetrable state and corporate organisations is, alas, all too true to life. The idea of the honest, conscientious American citizenry putting a stop to crimes such as Ellsberg exposed is ultimately illusory. Some more concrete social agent is necessary - an agent with its own newspapers and other media, its own ‘intelligence agencies’ perhaps, reporting on the activities of the enemy; indeed a clear sense that there is an enemy, that contemporary society is inherently antagonistic, and pacifism is therefore false.

Nonetheless, the fact that a wholly institutionalised member of the intelligence apparatus could become a principled pacifist, and place himself repeatedly in danger of arrest and violence in the service of his programme, ought to give us some hope. The power of these agencies is not, in the end, complete - something that is good in humanity rebels against being so employed, to make plans for the use of genocidal weapons or military tactics, and to drown every insult to imperial pride in blood.

Daniel Ellsberg, above all, exemplified that spirit, and for that we must pay our respects.