04.12.2025

No trust in judges

Government attacks on trial by jury must be resisted by all democrats and socialists. We should not only fight to extend trial by jury: we should also demand the election of judges, says Paul Demarty

It would, of course, be the government of Sir Keir Starmer - former director of public prosecutions - that undertook the most extensive assault on jury trials in living memory.

Lord chancellor David Lammy is in charge of this little initiative, and he is responding to an earlier report by Brian Leveson - a senior judge, probably best known for helming the interminable inquiry into phone hacking. Leveson’s report recommended suspending the right to a jury trial for offences that carried a maximum sentence of three years. This was not enough for Lammy, who seemed to prefer five years, although, apparently under pressure from aghast cabinet colleagues, he seems to have retreated to the Leveson standard. Magistrates will have their sentencing powers increased, and a fast-track system of judge-only courts is to be created.

The official justification is of the narrow, penny-pinching, petty bourgeois sort. There is a huge backlog of cases; the machinery of justice, of which we Brits are unjustly proud, must clank ever onward. There are jail cells to fill (though notoriously not enough), keys to throw away. Judges will be able to get through everything much quicker.

Canonical trials

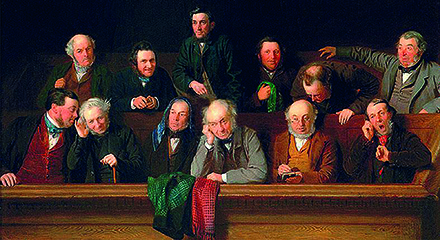

Of course, the jury system - as Mike Macnair reminded readers of this paper a couple of years ago - began as a way of speeding things up.1 In the 12th century, canonical trials - overseen by a single judge - had become impossibly dilatory. This was because judges could not, in fact, be trusted, and so any case could be appealed up through the ecclesiastical hierarchy, all the way to the pope himself. Spurred on by King Henry II, the use of various local notables to oversee the peculiar judicial practices of the day - trial by combat, or by ordeal - evolved into the jury system roughly as we know it, such that it was enshrined famously in Magna carta in 1215.

Are today’s judges to be trusted? The idea has gotten into modern intellectual culture that they are now mere technicians - “automatic statute-dispensing machines”, in Max Weber’s sardonic phrasing. We will look more deeply into this later, but an unavoidable part of the context for this decision, for all the philistinism of the ministry of justice’s justifications, is the troubling habit juries have of reaching the wrong decision. Comrade Macnair’s article responded to Tory outrage at acquittals of activists in Palestine Action, Extinction Rebellion and Black Lives Matter.

The other significant legal story of the present situation, after all, is the current judicial review of the preposterous proscription of Palestine Action as a “terrorist organisation”. Asa Winstanley of Electronic Intifada spotted something fishy about this appeal: there was a last-minute change behind the gavel. Out went high court judge Martin Chamberlain, a free-speech specialist, and in came a panel of three judges led by Victoria Sharp, who has family connections and employment history that imply sympathy for the state of Israel.2

Of course, family connections do not necessarily mean anything - Ms Sharp may be a scrupulous straight arrow. Even so, it is a reminder that the very fact that this matter - of decisive importance for free speech, such as it is, in this country - is not coming before a jury. The Kafkaesque monstrosity that is “anti-terrorism” legislation definitionally has no room for juries of one’s peers: one wing of the establishment - the judges - is told in secret of the evidence concocted by another - the security services - and makes a determination on that basis.

Explanation

David Lammy’s big scheme, thus, has three layers of explanation. One is the economic pressures that are the official explanation, and are hardly wholly fictional. Another is the interests of the judiciary and legal profession per se. Finally, there is the general authoritarian drift of British society.

So to that backlog of 100,000 cases then. Opponents of the scheme have concentrated on the question of whether these changes will actually work. Not much of this backlog, it turns out, is for stuff that carries a maximum sentence of less than five years, never mind three. Yet that is perhaps the wrong question to ask. There has been no apocalyptic crime wave in the last few years, despite hysterical rightwing commentary to the contrary. There was no such backlog in times when the crime rate genuinely was much higher.

The reality is that this is the legacy of a long period of underinvestment. Such underinvestment shows all the signs of being deliberate. It is a common trick in the neoliberal era: run something down so it goes to ruin and therefore there is “no choice” but (usually) to privatise the whole thing.

In this case, the object is different. Governments have been chipping away at the jury system for decades - recently, defamation cases were removed from its purview, and we have already mentioned the way that anti-terror law allows the state machine to suspend ordinary means of justice. (The Palestine Action judicial review is, of course, by definition a judge-led thing, but we are only here because the government was able to impose draconian measures against the organisation on its own steam.) Cuts to legal aid - another means of denial of justice - have no doubt gummed up the works further.

Secondly, we come to the judiciary as such - for whom this amounts to a power grab. The hegemonic liberal-constitutionalist mode of statecraft has very great esteem for the judiciary, as a check on the power of the government. But we must inquire into what power, and protection for whom. The supposition that the judge is ’independent’ likewise demands an answer: independent among whom?

To be too brief (and to speak only, here, of the judicial power in modern capitalist societies), the judiciary is independent among capitals, when it is not wholly suborned (as it often is). It is to be relied on in contractual disputes, in rough proportion to the size of the capitals arrayed against each other in such pursuits. It protects capital from popular sovereignty, from the ‘tyranny’ of incursions into its property.

Of course, the judiciary - and the justice system more generally - offers some protection to ordinary Joes like us. It convicts murderers, whose victims are overwhelmingly poor, at some kind of rate. It defends some of us, some of the time, from openly fraudulent abuse by capitalist firms. Ideally, it will do enough of this sort of thing to ensure ‘legitimacy’, which is expended on defending capital.

Judges reliably defend capital for perfectly straightforward reasons. A judge, in the end, is a lawyer successful enough to be promoted to the bench. A successful lawyer - in the modern ‘free market in legal services’ - is one, crudely, who commands large fees; and one commands large fees by having wealthy clients and achieving success in their interests. A judge, on average, is someone therefore unusually supportive of arguments in favour of the power of capital.

He or she is, therefore, also usually establishmentarian more generally. Loyalty transfers to the institution of the state. Judges have offered no resistance whatsoever to the flagrant incursions on popular liberty that have only multiplied since the outset of the war on terror. They have, however, whitewashed state crimes (Lord Hutton and his inquiry), protected the state from the consequences of major scandals (Leveson himself, who reduced phone-hacking to a matter of press ethics and basically ignored the direct complicity of the police and senior politicians in the Murdoch empire’s skulduggery); and invented novel instruments like the superinjunction to silence news stories unfavourable to major corporations.

Authoritarian

By handing over more and more powers to judges, governments tend to enervate what democracy we enjoy in our absurd, chimerical constitution. And this, finally, is part of a wider tendency. For what democracy we enjoy is the fruit of our ability, in the workers’ movement, to impose concessions on the state. With the defeat of the workers’ movement in the Thatcher years, we have lost the ability to do so, and so politics, and broader social life, has become progressively more authoritarian, judicialisation - ‘juristocracy’, to borrow a word from Ran Hirschl - being one method of bringing this outcome about.

Those, like Simon Jenkins of The Guardian, who argue that jury trials are anachronistic therefore have a point. They are anachronistic from the point of view of a society where all levers of popular power are being broken one after another. With a jury, one must always ensure that a prosecution is not only legitimate, but just in a fuller sense. It is an imperfect mechanism for doing so, especially in a time of generally dismal class consciousness. Yet the ‘wrong’ answer, given in cases like the Colston Four (anti-racists who dumped a statue of a slave trader in Bristol Harbour in 2020), is a standing insult to the cosy arrangements of the elite.

Wider picture

Though such cases will be front of mind for leftists when considering Lammy’s proposals, it is important to see the wider picture. Trial by jury, though stumbled upon almost by accident by English kings nine centuries ago, has proven a sticking point in all great social upheavals in this country for a reason. It really is a democratic institution - subject to deformations typical of our fundamentally undemocratic economic system to be sure, but a check on the arbitrary power of the ruling class over us: the only ‘check and balance’ worth having. In a future socialist society, it will remain a check against the bureaucratic degeneration that we know, from the history of the 20th century, is a grave danger.

It should be defended, and extended at a minimum to all criminal cases where prison is a possibility. Further measures to neuter the overwhelming power of capital and the state to suborn the courts will also be necessary - crucially the election of judges with term limits. The left, finally, should take note of these matters, even when there is not some immediate relevant flashpoint, like the Colston case or Palestine Action.

The task of delegitimising the judiciary, and fighting to bring it to heel, is always before us.

-

‘Defend and extend the jury system’ Weekly Worker November 23 2023: weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/1468/defend-and-extend-the-jury-system.↩︎

-

electronicintifada.net/content/judge-palestine-action-case-has-ties-israel-lobby/51085.↩︎