16.10.2025

She gave us the truth

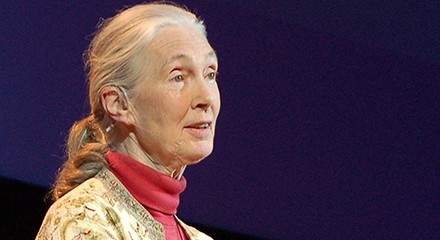

Scientist, animal rights activist and an extraordinary revolutionary. Above all, though, Jane Goodall showed us what chimpanzees can teach us about human nature. She should be an inspiration for us all, says Chris Knight

Jane Goodall died on October 1, aged 91. She will be remembered not only as a passionate animal rights activist, but as the scientist who made history as the first to describe chimpanzee life in the wild, instead of just in a zoo.

Goodall was a vegetarian and, eventually, a vegan. Fortunately, she was too honest to project her values onto the chimpanzees she spent her life studying. Shunning theoretical arguments in favour of reportage, she gave us the truth.

In the pre-Goodall era, chimps had been viewed as loveable vegetarians, munching fruit in the trees, while living in peace and harmony. ‘Nature good, culture bad’ was a widespread popular assumption. The idea was that only humans had lost touch with nature - so much so that they manufactured artificial weapons, shed blood, patrolled territorial boundaries and waged war against creatures of their own kind.

Goodall changed all this. In 1960, she set out to study the chimps living in a forested region of what is now Tanzania, helping establish the Gombe Stream Reserve. At first, the animals ran off on catching sight of a human intruder, so she could only view them through binoculars. Over time, however, Goodall’s patience produced rewards. Having won the trust of a particular chimpanzee, she gave him a name - ‘David Graybeard’.

Had Goodall been scientifically trained, she would not have been allowed to do this. Names should be avoided - so it was said - to prevent observers from investing chimps inappropriately with human emotions. The correct procedure was to label each animal with a number.

Untrained as she was - lacking even a degree - she took no notice. She named and followed one chimp after another until eventually she could identify every one. She was delighted to discover how each had its own unique personality and network of relationships. Their facial expressions, hugs, kisses, pats on the back and gestures of reassurance seemed immediately comprehensible, because human body language is essentially the same. As Goodall settled into chimpanzee society, she felt at home.

Apes and violence

Although she never lost those feelings, they soon became tinged with alarm. Her new friends were certainly not vegetarians. From time to time, the whole community would be seized with frenzy. A colobus monkey had been noticed high up in the trees. Several chimps would start climbing towards it, while others blocked off its escape routes. Without powerful canines or piercing weapons, the chimp hunters had difficulty killing the helpless creature, once it had been caught. Often they would begin eating the monkey while it was still alive, rival males pulling in different directions until it eventually died from being torn apart.

Still more alarming to Goodall were the internal fights. Rival male groups would mount raids into one another’s territory, searching for an isolated victim to kill. Many of Goodall’s feminist admirers criticised her for describing such things, accusing her of contributing to the reactionary idea that male violence and warfare are inescapable, being inherited from our ape-like ancestors. Of course, Goodall’s actual position was always that while bloodthirsty violence is part of human nature, harmony and cooperation are consistent with our nature too.

I remember attending a scholarly meeting in London, where, to a shocked audience, Goodall revealed the gory details of warfare between neighbouring chimpanzees. Years later, she recalled her feelings on first witnessing such scenes:

Often when I woke in the night, horrific pictures sprang unbidden to my mind - Satan cupping his hand below Sniff’s chin to drink the blood that welled from a great wound on his face; old Rodolf, usually so benign, standing upright to hurl a four-pound rock at Godi’s prostrate body; Jomeo tearing a strip of skin from Dé’s thigh; Figan, charging and hitting, again and again, the stricken, quivering body of Goliath, one of his childhood heroes.1

When a conflict involves many males on each side, casualty rates can be high. Her observations meant that Goodall was reaching conclusions about our closest animal relatives in a completely fresh way, in many respects at variance with accepted wisdom.

Apes and tools

When I first began thinking about chimpanzees, a widespread view was that the emergence of our species was made possible in the first instance by an ‘opposable thumb’. Once our thumbs could swivel round and connect up with our fingers, so it was said, our ape-like ancestors could at last begin holding objects with a precision grip - a precondition for the manufacture of stone tools.

Then came Jane Goodall. ‘David Graybeard’ had shown her how he and other chimps make ingenious tools for pulling fruit within reach, catching and eating termites and numerous other tasks. The opposable thumb narrative now seemed irrelevant. Chimps possess an opposable thumb for very good reasons, since they routinely grip overhead branches to steady themselves and keep upright, as they move through the trees. In addition to apes and many other primates, it is now known that opossums, pandas, koalas and even some frogs all have opposable thumbs!

I had never been happy with idea that the critical development in human origins was the evolution of an opposable thumb. I felt it was a way of side-stepping the real issues - the fundamentally social questions central to the argument of Marx in his Early writings and Engels in The origin of the family, private property and the state. Labour can be performed with or without tools. According to Marx in his early writings, labour came into existence from the moment individuals began producing food, shelter and other necessities of life not merely for themselves as individuals, but for one another’s benefit.2

It would have been at least a million years before the stone tools made by our distant human ancestors became involved in incipient forms of genuine labour. Certain of the tools made from wood or stone had points or sharp edges designed for cutting into flesh. Hunting? Scavenging? These were certainly possibilities, but fighting would equally have been an option. Imagine Goodall’s chimpanzees attempting to kill one another using specially designed stone weapons. Had our ancestors continued behaving like apes, the most likely consequence of tool-use would have been extinction.

Apes and Engels

As I began taking an interest in chimpanzees during the 1960s, I was hesitantly aligning myself with the prevailing Marxist current on my campus at Sussex University. I remember pestering my Militant Tendency comrades with questions about how communism would work. Did history provide evidence of a revolution whose enduring outcome measured up to the revolutionaries’ hopes and ideals?

As I carefully studied Engels, I became inspired by his argument that humanity itself must have undergone some kind of revolution to arrive at language and symbolic culture. In his own words, systems of primate dominance have “a certain value in drawing conclusions regarding human societies - but only in a negative sense”. There are no obvious evolutionary continuities. As ape males fight over access to females, jealousies explode into violence. Engels continues: “Mutual toleration among the adult males, freedom from jealousy, was, however, the first condition for the building of those large and enduring groups in the midst of which alone the transition from animal to man could be achieved.”3 Engels was explaining that, for our ape-like ancestors to become fully human, a social revolution was required.

I can imagine sectarians on the left dismissing Goodall as a middle class scientist and climate activist, having little in common with Marxism. In my view, attitudes of that kind are absurd. Spending so much of her life interacting with chimpanzees, Goodall was never likely to find proletarian class politics particularly relevant.

But, before turning away, readers should give themselves a treat. Watch Netflix’s astonishing ‘Famous last words’ interview with Jane Goodall.4 Describing herself as a resolute anti-fascist, she lashes out at Elon Musk, Donald Trump, Vladimir Putin and - with special venom - Benjamin Netanyahu. Eyes flickering with rage and humour, she said she would love to put them on one of Musk’s rockets to a distant planet, leaving the rest of us alone.

For a thinker to qualify as a revolutionary, they need not necessarily champion Marx. The litmus test is whether they base their political activism on science. In that respect, Jane Goodall was an extraordinary revolutionary - an example and inspiration to us all.

-

J Goodall Through a window: thirty years with the chimpanzees of Gombe London 1991.↩︎

-

“Insofar as man is human and thus in so far as his feelings and so on are human, the affirmation of the object by another person is equally his own enjoyment” - quote from Karl Marx. See D McLennan (ed) Early texts Hoboken NJ 1972, pp178-79.↩︎

-

www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1884/origin-family/ch02.htm.↩︎

-

edition.cnn.com/2025/10/06/politics/video/jane-goodall-netflix-famous-last-words-posthumous-interview-vrtc.↩︎