18.09.2025

The road from Eton College

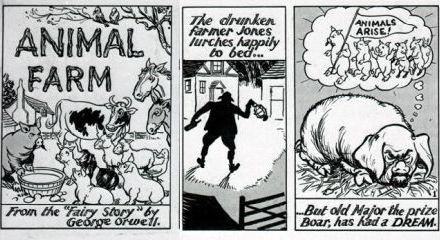

Seventy-five years after George Orwell’s death, Paul Flewers, in the fourth part of his series, focuses on the establishment’s ideological misuse of Animal farm

World War II entered a new phase after the German assault upon the Soviet Union in June 1941. One immediate result was that the USSR rapidly changed in people’s perception from being a near-ally of Nazi Germany into a staunch and respected ally of Britain. After December 1941 the same happened in the USA as well. The rehabilitation of Stalin and the Soviet Union was not so much a return to the fellow-travelling days of the late 1930s, but part of the wartime ideology in Britain. It went much further, with the British government being obliged to give official approval to the USSR - an endorsement which was simultaneously fulsome and uneasy.1

Whilst respect for the Soviet Union in its fight against Nazi Germany was to a large degree a refracted form of British patriotism - one account stated that “criticism of the USSR became tantamount to treason”2 - it could not avoid being conflated with the idea of the perceived superiority of a planned economy, and even with the idea of socialism.3 Only a tiny handful of people at various obscure points across the political spectrum refrained from joining in the Stalin worship. George Orwell was one of them.4

Peak prospect

It was almost typical of Orwell that at the peak of British respect for the Soviet Union he should write a novel that was a sharp polemic against Britain’s wartime ally. Needless to say, he had considerable problems getting Animal farm published,5 and even when it was released by Secker and Warburg, it was shorn of its polemical foreword, thus helping to rob it of its contemporary relevance.

The unpublished foreword to Animal farm showed Orwell’s great concern about “the prevailing orthodoxy” of the “uncritical admiration of Soviet Russia”, which he considered was encouraging extremely unwelcome and ominous tendencies amongst British intellectuals. He flailed out at the “veiled censorship” operating in their circles:

At any given moment there is an orthodoxy - a body of ideas which it is assumed that all right-thinking people will accept without question. It is not exactly forbidden to say this, that or the other, but it is ‘not done’ to say it - just as in mid-Victorian times it was ‘not done’ to mention trousers in the presence of a lady. Anyone who challenges the prevailing orthodoxy finds himself silenced with surprising effectiveness. A genuinely unfashionable opinion is almost never given a fair hearing, either in the popular press or in the highbrow periodicals.6

He stated that, from the early 1930s, the bulk of British intellectuals had consistently accepted the Soviet viewpoint “with complete disregard to historical truth or intellectual decency”. One could not obtain “intelligent criticism or even, in some cases, plain honesty” from writers and journalists who were “under no direct pressure to falsify their opinions”. Moreover, “throughout that time, criticism of the Soviet regime from the left could only obtain a hearing with difficulty”. Most of all, he decried the trend amongst intellectuals towards restricting the expression of oppositional ideas that were seen as “objectively” aiding an enemy - a process leading towards the destruction of “all independence of thought”, and to a “totalitarian outlook”.7

Although, as we shall see, Orwell was well aware that the tendency towards self-censorship went a lot further than the radical intelligentsia, here he was aiming his criticisms specifically at the leftwing intellectuals who refused to criticise the Soviet regime, when it committed acts that would be roundly condemned if perpetuated by another. For Orwell, the “willingness to criticise Russia and Stalin” was “the test of intellectual honesty”.8 His message to pro-Stalin intellectuals was brutal: “Do remember that dishonesty and cowardice always have to be paid for. Don’t imagine that for years on end you can make yourself the boot-licking propagandist of the Soviet regime, or any other regime, and then suddenly return to mental decency. Once a whore, always a whore.”9

Predicament

As for the novel itself, there can be no doubt that Animal farm is based upon the experience of the Soviet Union - from the Russian Revolution, through the emergence and victory of Stalinism, to the wartime years. Some of the characters are eponymous. The taciturn, devious and ambitious Napoleon is clearly Stalin, and the more inventive and vivacious Snowball is an equally obvious Trotsky - although he “was not considered to have the same depth of character” as Napoleon, which is an odd characterisation.10

There is, however, no porcine Lenin, as Major (Marx) dies just before the animals take over the farm, although the displaying of Major’s skull is reminiscent of the rituals around the embalmed Bolshevik leader. The pigs as a whole represent the Bolshevik Party, the thuggish dogs are the secret police and the other animals mainly represent the Soviet working class and peasantry.

Although Orwell’s sympathies are clearly with the animals, and their revolution against Farmer Jones is celebrated, his overall view of them is not particularly complimentary. The pigs - the most intelligent and the only literate creatures - move immediately into a commanding position because of their superior intelligence, and become an increasingly ruthless ruling élite. The sheep are the most stupid, unable to command even the basics of the animalist credo, and are merely able mindlessly to bleat slogans at official command. Boxer, the big carthorse, is practically illiterate, and represses his occasional worries that things are going awry with his mantras of “I will work harder” and “Napoleon is always right”. Even though the animals attempt unsuccessfully to prevent the exhausted Boxer from being taken to the knackery, they willingly believe the pigs’ tale that he died at the vet. Not surprisingly, many commentators, both friendly and hostile, have accused Orwell of having a low opinion of the working class.11

Despite the fact that the humans - that is to say, the capitalists - in Animal farm are from start to finish presented in a deeply negative light, it is not surprising that the novel was and continues to be championed by liberals and conservatives for anti-socialist purposes.12 The moral of this book appears to be that, however awful the old rulers are, revolutions merely lead to the emergence of new and possibly more oppressive elites.13

At the end of the book, a by-now bipedal and clothed Napoleon shows a delegation of humans around the farm. He tells them that the old revolutionary symbols and rituals have been abolished. It is clear that the other animals know their place. Having greatly cheered his visitors, they sit down to celebrate, only to come near to blows when they find themselves cheating at cards. The animals peering through the windows see that the pigs and men have become interchangeable: “… it was impossible to say which was which”.14

The main problem with Animal farm is that there is no analysis of how a ruling elite came into existence. The development of the pigs from a leadership into a ruling elite is just a given: it is as if any leadership will inevitably become a ruling elite, once it seizes power.15 Orwell attempted to reassure the American libertarian, Dwight MacDonald, stating that he was referring to a revolution led by “unconsciously power-hungry people”, and insisting that the moral of the book was: “You can’t have a revolution unless you make it for yourself; there is no such thing as a benevolent dictatorship.”16 But that is not how the book is usually interpreted, and MacDonald’s qualms would not have arisen were it otherwise.17

Stanley Plastrik, an American socialist, even wondered if Orwell had renounced socialism: “Is not the anti-socialist or liberal reader entitled to draw the conclusion that the tale is meant as a parable on the utopian character of the socialist cause? We believe so, although Orwell has not had the political conviction or courage to make this clear, perhaps reflecting the very uncertainty reigning in his head.”18

Of course, using different sorts of animals to represent social strata ensures that there will be insurmountable barriers from the very start. A cat or dog, let alone a goose or duck, cannot become a pig, whatever the objective conditions; but a revolutionary can become a bureaucrat, a revolutionary leadership can become an elite.

No renunciation

And that is what happened in the Soviet Union. It is Orwell’s inability to explain the rise of a post-revolutionary elite which led to his book being championed by liberals and conservatives. Although he was worried about this,19 Animal farm became popular with liberals and conservatives precisely because it sees the pigs’ ascendancy into a ruling elite as an ineluctable process. If it did not, it could not be used as a anti-socialist work.

Animal farm did not represent any renunciation on the part of Orwell of the socialist cause. Rather, it was intended to show the need for a libertarian brand of socialism.20 His opposition to both capitalism and totalitarian collectivism remained constant. Reviewing Hayek’s anti-socialist tract The road to serfdom, Orwell noted:

Capitalism leads to dole queues, the scramble for markets, and war. Collectivism leads to concentration camps, leader worship and war. There is no way out of this unless a planned economy can be somehow combined with the freedom of the intellect, which can only happen if the concept of right and wrong is restored to politics.21

This predicament was to be the axis around which much of Orwell’s future writings would revolve.

-

P Addison The road to 1945: British politics and the Second World War London 1982, pp127-63.↩︎

-

FS Northedge and A Wells Britain and Soviet communism: the impact of a revolution Basingstoke 1982, p151.↩︎

-

A Calder The people’s war: Britain 1939-1945 London 1992, pp260ff, 298, 348ff. The government’s fears about this are described in PMH Bell John Bull and the bear: British public opinion, foreign policy and the Soviet Union, 1941-1945 London 1990, pp42, 67. The membership of the CPGB rose from 22,783 in December 1941 to 56,000 in December 1942, although it dropped off to 45,535 by March 1945 (see N Branson History of the Communist Party of Great Britain, 1941-1951 London 1991, p252).↩︎

-

Even then, Orwell praised the Soviet system in his BBC wireless broadcast on May 2 1942: see WJ West Orwell: the war commentaries New York 1986, pp85-87. He did, however, later write off his BBC work as “bilge” (G Orwell, ‘Letter to Stafford Cottman’ Collected essays, journalism and letters (CEJL) Vol 4, Harmondsworth 1984, p180).↩︎

-

For the problems Orwell encountered with publishers, see B Crick George Orwell: a life Harmondsworth 1982, pp452ff.↩︎

-

New Statesman August 18 1995. Orwell suffered the indignity of having a book review rejected by the Manchester Evening News in March 1944 because it was critical of the Soviet Union: see B Crick George Orwell: a life Harmondsworth 1982, p463. Paul Addison wrote of the “near monopoly which communists and fellow-travellers possessed over the supply of information and publicity material about Russia” during the war: see P Addison The road To 1945: British politics and the Second World War London 1982, p138.↩︎

-

New Statesman August 18 1995.↩︎

-

G Orwell ‘Letter to John Middleton Murry’ CEJL Vol 3, p237.↩︎

-

G Orwell ‘As I please’, September 1944 CEJL Vol 3, p263. Nonetheless, Orwell stated that if, as he thought likely, intellectual opinion were to turn against Stalin, “I should not regard this as an advance … What is needed is the right to print what one believes to be true, without having to fear bullying or blackmail from any side.” (G Orwell, ‘Annotations to Randall Swingler, “The right to free expression”’ CW Vol 18, London 1998, p443; see also New Statesman August 18 1995).↩︎

-

G Orwell Animal farm Harmondsworth 1973, p15. Orwell originally portrayed “all the animals, including Napoleon,” as having “flung themselves on their faces”, when the windmill was blown up, but at the last moment before publishing he replaced the word “including” by “except”, on the grounds that Stalin did remain in Moscow in June 1941 during the German advance: see G Orwell ‘Letter to Roger Senhouse’ CEJL Vol 3, p407. We now know that Orwell’s original portrayal was more accurate, as Stalin seems to have experienced a serious breakdown and went into hiding for a few days.↩︎

-

For friendly appraisals, see J Molyneux ‘Animal farm revisited’, in P Flewers (ed) George Orwell: enigmatic socialist London 2005; for hostile appraisals, see J Walsh (‘George Orwell’ Marxist Quarterly January 1956), who shows what the CPGB thought of him.↩︎

-

Anne Applebaum, a young conservative writer, contended: “It is one of the best books on the psychology of revolutions. It acts as a kind of blueprint for the way revolutions actually happen, and, as I observe more revolutions in my later life, it becomes more accurate.” The Independent August 14 1995.↩︎

-

John Mander considered that there was a dichotomy in Orwell’s thinking, in that “there must always be revolutions”, but that “all revolutions are totally useless” (J Mander ‘Orwell in the sixties’, the writer and commitment Westport 1975, p96). Patrick Reilly agreed, and stated that “Animal Farm and 1984 are authenticated by the fact that their creator did not want them to be true” (P Reilly 1984: past, present and future Boston 1986, p267).↩︎

-

G Orwell Animal farm Harmondsworth 1973, pp119-20.↩︎

-

Well before Animal farm, Orwell had betrayed a fatalistic streak regarding revolutionary leaderships: “It would seem that what you get over and over again is a movement of the proletariat which is promptly canalised and betrayed by astute people at the top, and then the growth of a new governing class” (New English Weekly June 16 1938).↩︎

-

G Orwell ‘Letter to Dwight MacDonald’ CW Vol 18, p507.↩︎

-

In 1947 Frank Ridley of the Independent Labour Party warned that socialists had to be very careful when criticising Stalinism, stating that Animal farm, “justifiable enough in itself”, was “a godsend to Wall Street imperialism in mobilising public opinion against Russia” at a time when the USA was “preparing to attack the Soviet Union”. He even went so far as to see Orwell as one of “the ‘left’ propagandists of Wall Street”, alongside the US social democrats (Left June 1947).↩︎

-

Labor Action September 30 1946.↩︎

-

See Alfred Ayers’ comments in S Wadhams Remembering Orwell Markham 1984, p68.↩︎

-

See Fenner Brockway’s comments in S Wadhams Remembering Orwell Markham 1984, p150.↩︎

-

G Orwell, ‘Review’ CEJL Vol 3, p144. Note that Orwell did not include alongside “the freedom of the intellect” the popular control of the means of production as an essential anti-totalitarian criterion.↩︎