10.07.2025

Civility and its discontents

Lessons from Martin Luther and the Hobbesian demand for speech controls. Can we build a workable communist movement without ruthless truthfulness, even at the cost of giving offence? Paul Demarty thinks no

The (hopefully temporary) withdrawal of the Talking About Socialism group from the Forging Communist Unity project a few weeks ago was a setback.

Yet in a certain respect it represented progress. We have had a few run-ins with the leaders of this tendency over the years, drawn close only for relations to collapse. On most of these occasions, the substantive reasons offered have been trivial, if not the differences in method that led, precisely, to the prominence of such trivialities. This time round, we are at least fighting - or are hopefully soon to be fighting - over something that really does matter. Indeed on this it matters more than anything else: programme.

The obstacles to our commencement of this battle - or, who knows, an outbreak of spontaneous agreement! - are principally the TAS comrades’ feeling of unpreparedness. As they wrote in their letter announcing a pause in their engagement in FCU, to allow them to finish “produc[ing] our own draft programme for consideration in the FCU process. We have not so far been able to do so. For that we apologise”.1 That is all fair enough - we do not believe in hurrying such matters.

Yet underlying this problem is another running difficulty - the comrades continue to believe that we are just too rude, that we traffic in accusations of political unsoundness that are beyond the bounds of ‘comradely argument’. At the last TAS meeting, which several CPGB members attended, Nick Wrack objected to the accusation of Bakuninism, and constructed various other political criticisms of a policy of pursuing revolution in a single country as an accusation that he secretly wanted to set himself up as a British Pol Pot.

Melvyn Bragg

By chance, In our time - the upper-middlebrow BBC radio programme in which Melvyn Bragg has amiable discussions with various intelligent guests - chose, last week, to produce an episode on civility, especially in political life. His guests were historians, and, interestingly, chose as the meaningful historical frame European history since the Renaissance and the early modern period.2

The narrative goes something like this: the ascendant merchant class of Italy needed its own rules of conduct and internal culture - what Bourdieu called habitus - apart from that of the pre-existing class of aristocrats, descended, ultimately, from the grandees of the old empire. The spread of sets of rules of civility, sped by the invention of the printing press, provided an essential part of this formation. These ideas of civil conduct spread internationally, such that upwardly mobile layers as far afield as Britain adopted an essentially ‘Italianate’ version of the same.

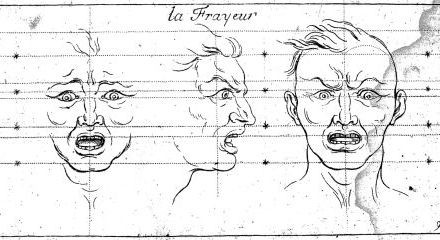

Yet Europe was on the brink of an ideological crisis - the Protestant reformation. The man who lit the touch-paper, the German Augustinian friar, Martin Luther, could justly be rebuked with many things: his anti-Semitism, his conservatism in relation to the revolutionary elements of the Reformation, and so forth. But he could never be fairly accused of mincing his words. His criticisms of the Catholic church - its sale of indulgences, the idle parasitism of its religious orders, its arrogation to itself of matters which properly belonged to ‘god’s grace’ alone - were stated baldly, and he did not move from them, going on famously to denounce the Pope as anti-Christ.

Moreover, he took up his ideological cudgels against those, like Erasmus, who agreed with much of the substance of his case, but supposed that open doctrinal warfare on the established religion of Europe was not the way to go about things. Their politeness seemed very commendable, but in the end simply dragged them into the anti-Christian mire. Excremental imagery is common in Luther’s polemics, perhaps coincident on his own rather severe bowel problems (as the hosts of Chapo Trap House once quipped, if Napoleon is history on horseback, Luther is history on the toilet).

To modern readers - especially largely atheist readerships like that of this paper - the back and forth between Luther and his Catholic opponents may seem hopelessly overheated, given that the points in dispute are basically recondite details of Augustinian theology. I ask the indulgence - no pun intended - of such readers here; even if it is obscure for us, these were extremely grave matters for the contestants, having to do ultimately with whether the uncounted masses of Europe were to lose the favour of providence on Earth and burn in eternal hellfire thereafter. The sheer devastation of the later wars of religion tended, rather, to underline the point for zealous Catholics, Lutherans and Calvinists.

Contemporaneously with this period of war, we meet the next great hero of the In our time panel: Thomas Hobbes, the first major modern figure of English political thought. He is best known for his theory of the state along absolutist lines, as laid out in Leviathan, but Hobbes had also undertaken the Grand Tour in his youth and picked up Italian ideas about civility. These he applied especially to religious matters - unsurprisingly, given the bitterness of religious conflict in the 17th century and the role religion played in the civil war. (He was, of course, on the wrong side, and spent some considerable time in exile in Paris.) For Hobbes, the essential thing was always the proper functioning of the state and, to ensure its functioning, gentlemen in good standing had to abstain from zealotry and treat ideological opponents with the greatest civility.

Hobbes had an advantage over the zealots he opposed, however, which was that he did not in fact share any of their substantive views. By the standards of his own day, he was vulnerable to accusations of atheism, though he would not be so described today. His views are comparable to the later Deist movement, or - in a different, but more pertinent, way - to those of his contemporary, the famous French statesman, Cardinal Richelieu, whose religious views, though formally Catholic, were wholly determined by a specific view of France as a favoured nation. (Richelieu happily armed Protestant armies against Catholic ones in the wars of the time, so as to knock the hated Habsburgs down a peg.)

Having spun things against Hobbes’s view in the foregoing, we cannot dismiss it as wholly senseless. After all, the wars of this century were no small matter. Something like eight million people perished in the overlapping series of central European conflicts called the Thirty Years War. If discretion and polite conduct could draw the sting of such devastation, then it was surely worth the cost. In truth, it probably could not have done - that conflict was fired in the minds of many of its soldiers by religious disputations, but its real engine was indisputably the rivalry between the Habsburg and Bourbon dynasties, and surely would not have dragged on half as long without such vast material interests at play.

Friendship

Hobbes’s view is nonetheless intelligible, to say the least, and transfers more plausibly to the smaller scale of individuals, families and communities of friends. We all - don’t we? - put things delicately, avoid sore spots, because we do not want to undermine some friendship. This is not obviously wrong. Friendships, in the narrow sense of merely having cordial relationships with people close to you in time and space, are valuable in themselves; their preservation is good. This view was put remarkably bluntly by Nietzsche in Human, all too human:

Just think to yourself some time how different are the feelings, how divided the opinions, even among the closest acquaintances; how even the same opinions have quite a different place or intensity in the heads of your friends than in your own; how many hundreds of times there is occasion for misunderstanding or hostile flight. After all that, you will say to yourself: ‘How unsure is the ground on which all our bonds and friendships rest; how near we are to cold downpours or ill weather; how lonely is every man!’ … [And you] will admit to [yourself] that there are, indeed, friends, but they were brought to you by error and deception about yourself; and they must have learned to be silent in order to remain your friend; for almost always, such human relationships rest on the fact that a certain few things are never said.3

Nietzsche’s view has the advantage of placing upfront the cost - of silence, of retreat from the truth. Which poses the problem acutely: we have two competing goods - friendship and truthfulness. The decision to be made is not whether or not either truly matter, but what order they go in - which, in extremis, is to be sacrificed to the other.

It is impossible to make that decision in a vacuum. Yet it seems that at least the possibility of truthfulness, even at the cost of friction, is something essential to friendship - that, pertinently, distinguishes it from good relations between managers and subordinates. I once stood on a London Bridge train platform with two Millwall casuals. The driver - a woman - made some announcement over the PA, audible through the open doors, and one of the casuals joked that, if the driver was female, he wasn’t getting on after all. His friend pointed out that he had no objections to women drivers, when it was his wife picking him up from the pub - the justice of which point was immediately conceded. This seems to me a picture of real friendship, as opposed to mere comity.

If truthfulness is to be preferred, civility can only ever be conditional. Needless offence is, of course, to be avoided, but where there are real disagreements, or even just real dilemmas to be worked through, things must be posed sharply. When we come to the point of decision, the stakes of the decision must be understood by all in their true historical and theoretical depth.

Conditions of friendship transfer quite straightforwardly to political comradeship. It is essentially a relationship of putative equals, like friendship and unlike that between manager and subordinate (though, unfortunately, the managerial model is all too common in practice on the left), and one in which all participants are interested in truthfulness. To smooth over disagreements in the hope of getting along is merely to undermine the very purpose of the relationship. Indeed, the problems with keeping disagreements bottled up are starkly illustrated by the botched launch of the ‘Corbyn party’ in the last week.

Back to Wrack

So we return to comrade Wrack’s complaints about ‘Bakuninism’, etc. It is clear from the foregoing that this is, unfortunately, a regression to the level of unseriousness. Bakunin is a major figure in the history of the workers’ movement, and enormously significant movements have been built essentially on his ideas (for instance, the large anarcho-syndicalist organisations that grew in southern Europe and Latin America in the early 20th century). It is no insult to be accused of Bakuninism, but a political criticism.

As for Pol Pot - the trouble, of course, is that Pol Pot did not intend to become the Pol Pot of Cambodia. (Trotsky famously wrote that if Stalin had known in 1917 what he would have become by 1937, he would have shot himself.) The problem is the politics. How do we avoid getting stuck with the choice of brutality or capitulation? There is no way of talking seriously about this that ignores the moral stakes of the discussion.

Should we reach the organisational strength required for the general population to take us seriously, we will find that they want to know how we are to avoid repeating the disasters of the last century. They are quite right to seek such assurances. How are we to make such assurances to suspicious workers if we cannot even discuss them honestly amongst ourselves without having a shit-fit?

-

Nick Wrack and Edmund Potts, ‘Putting things on hold’ Weekly Worker June 5: weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/1541/putting-things-on-hold.↩︎

-

F Nietzsche (RJ Hollingdale trans) Human, all too human London 2015, p239.↩︎