29.05.2025

Questions of communism

What is the relationship between socialism and communism? Can socialism be built in a single country? Mike Macnair continues his exploration of the transition from capitalism

In the first article in this series last week,1 I identified its immediate context - our discussions in the Forging Communist Unity process about the nature and duration of the transition to socialism. I identified the fear that the CPGB is proposing a version of the ideas of ‘official communism’ as a part of the arguments. With this starting point, I discussed first the 1950s debate among Trotskyists, which had a similar (and, I think, related) theme. I went on to discuss a set of arguments about the topic of transition in the Communist Party of Britain’s Communist Review.

These, I argue, illustrate the fundamental differences between the CPGB’s views of the transition period and those of ‘official communism’. ‘Official communism’ clings to the ideas of separate national roads to socialism, leading to socialism in single countries, and to the people’s front policy of alliance with either liberal or nationalist capitalist parties - both on a world scale and within individual countries. It promotes bureaucratic rule as being ‘democracy’ (reflected in Britain’s road to socialism in a series of evasive expressions, and in the highly restricted form of pre-congress ‘discussion’ in the CPB).2 These political characteristics reflect the fact that ‘official communists’ refuse to draw any real lessons from the collapse of Soviet and east European ‘actually existing socialism’ and the increasing development of capitalism in China, Vietnam, Cuba …

The CPGB, in contrast, starts from a serious reassessment of why ‘actually existing socialism’ failed. It insists on the priority of political democracy, both in the state and in the workers’ movement. It insists on a class politics, which, while it does not urge the immediate expropriation of the petty bourgeoisie, does not subordinate working class interests to an imagined strategic alliance with the ‘national bourgeoisie’ or the ‘democratic bourgeoisie’. And it insists that the working class needs to develop proletarian internationalism and seize every opportunity available for common international action.

Kennedy

In this article I focus on Peter Kennedy’s article, ‘Differentiating socialism and communism’, posted on April 22 on the Talking About Socialism website.3 This has the merit of being a substantial argument, rather than just a short point or group of short points.

Comrade Kennedy begins with the statement that “the idea of socialism as an alternative to capitalism is an accepted common sense on most of the left”. This is true, I think, in Britain, the USA, Canada and Australia, and for the reason comrade Kennedy gives: a desire to take moral distance from the disastrous experience of Stalinism. In fact, it is for the same reason illusory. While the USSR lived, the capitalist states promoted ‘socialism’ (meaning loyalist ‘social-democracy’) as a more desirable alternative to ‘communism’. Once the USSR and its satellites fell, ‘socialism’ became just as much demonised in Anglo-American discourse as ‘communism’. Where there are surviving significant communist parties, ‘communism’ is still in use; where Eurocommunists have liquidated them, their remnants have abandoned ‘socialism’ too (thus the Partito Democratico in Italy, Syriza (the ‘coalition of the radical left’ in Greece). The Eurotrotskyists of the Mandelite Fourth International argue for the same course, with Anticapitalist Resistance in this country, the Nouveau Parti Anticapitaliste in France, and so on.

It is worth making a number of additional points here. The first is that there is no consistency in Marx’s and Engels’ usage of the terms. However, there are historical shifts in the use of the terminology, and these are important to understanding the present issue.

‘Socialism’ was not a synonym for communism in the Communist manifesto (1848). On the contrary, ‘socialism’ meant statist and nationalist political trends, variously characterised as feudal, petty-bourgeois, German, conservative-bourgeois, or critical-utopian. ‘Communism’ was the preferred term for the democratic-republican politics of appropriation in common of the means of production that the Manifesto promoted.

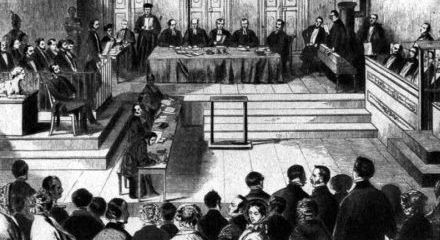

The conviction of the communists in the 1852 Cologne communist trial made it necessary for German leftists to use some other word to avoid instant prosecution; the Lassalleans used ‘workers’, the Eisenachers ‘social democratic’, to emphasise their insistence on political democracy (as opposed to the Lassalleans’ labour-monarchism); the unified party after 1875 was the ‘Socialist Workers Party’; after partial legalisation in 1890, ‘Social Democratic Party’ (SPD). The success of the SPD resulted in ‘social democratic’ becoming until 1914 the standard identifier for Marxist parties, as opposed to non-Marxist socialists.

The split in the Second International as a result of World War I and the Russian Revolution meant that identification with opposition to war and imperialism, identification with the Russian Revolution and standing for the overthrow of the liberal mixed constitution (falsely called ‘democratic’) made you a communist, even if, like the left and council communists, you broke with Comintern and Soviet policy. ‘Social democrat’ and ‘socialist’ were now identifiers for the pro-war, pro-imperialist and constitutional-loyalist right wing of the workers’ movement.

The ‘people’s front’ turn of Comintern led Trotsky to judge that the communist parties were now to the right of the left elements among the socialist parties, who maintained the traditional opposition to coalitions with bourgeois parties, and hence to promote the Trotskyists’ ‘French turn’ towards entry in the SPs. After this turn, Trotskyists began to use ‘socialist’ as a self-identifier.

In practice, however, Trotskyists were still identified by the broader movement as a variety of communists. To lose that identification would require giving clear commitments to imperialism, nationalism and loyalty to the existing constitution. Some groups, like the US Schachtmanites, did follow this path; most merely whinged about being identified with communism.

First phase

The second issue posed, intermingled in comrade Kennedy’s initial argument, is of ‘socialism’ as a synonym for what Marx in the Critique of the Gotha programme called the first phase of communism4 - or, alternatively, as a synonym for the political regime of working class rule or ‘dictatorship of the proletariat’, which is not quite the same thing.

The root of this usage on the modern left is in Lenin’s State and revolution: Lenin says that it is “usually called socialism, but termed by Marx the first phase of communism”. “Usually called” here shows that Lenin is not innovating. In fact, the usage can be corroborated from other left writers of the Second International. For example, Trotsky in Results and prospects (1906), chapters 7 and 8, uses ‘socialism’ in a way rather closer to the CPGB’s usage: that is, as a mixed economy under workers’ rule, tending more or less rapidly towards socialisation.5

From the 1920s on, this word-usage question became entangled with the issue of ‘socialism in one country’ (SIOC). Because the 1920s debate was not new, it is necessary to step further back to understand the outcome.

In the Communist manifesto, Marx and Engels had written that “United action of the leading civilised countries at least is one of the first conditions for the emancipation of the proletariat.”6 In the 1864 Inaugural address of the First International, it is remarked that “Past experience has shown how disregard of that bond of brotherhood which ought to exist between the workmen of different countries, and incite them to stand firmly by each other in all their struggles for emancipation, will be chastised by the common discomfiture of their incoherent efforts”;7 and, in the preamble to the general rules of the International, “That the emancipation of labour is neither a local nor a national, but a social problem, embracing all countries in which modern society exists, and depending for its solution on the concurrence, practical and theoretical, of the most advanced countries”.8 And in the Critique of the Gotha programme,

[Gotha draft] 5. “The working class strives for its emancipation first of all within the framework of the present-day national state, conscious that the necessary result of its efforts, which are common to the workers of all civilised countries, will be the international brotherhood of peoples.”

[Marx] Lassalle, in opposition to the Communist manifesto and to all earlier socialism, conceived the workers’ movement from the narrowest national standpoint.

He is being followed in this - and that after the work of the International! It is altogether self-evident that, to be able to fight at all, the working class must organise itself at home as a class and that its own country is the immediate arena of its struggle. In so far its class struggle is national, not in substance, but, as the Communist manifesto says, “in form”. But the ‘framework of the present-day national state’ - for instance, the German empire - is itself in its turn economically ‘within the framework’ of the world market, politically ‘within the framework’ of the system of states.9

It is worth noting that these arguments are not that international action is needed for the higher phase of communism, but that international action is immediately needed by the working class under capitalism and is “one of the first conditions for the emancipation of the proletariat” (emphasis added).

Georg von Vollmar, at the time a leftist (he went over to the right in 1891), offered a theory of The isolated socialist state in 1878.10 Karl Kautsky, who was in origin a Czech nationalist, already in 1881 argued that decision-making in socialism would be national (as opposed to local or international).11 And he maintained this belief in his exposition of the introductory part of the Erfurt programme in 1891, where he argued that socialism would imply a reduction of foreign trade, and that “A cooperative commonwealth co-extensive with the nation could produce all that it requires for its own preservation.”12 In his series of articles, ‘Nationality and internationality’, responding to the debate on the national question initiated by the Austrians, he argued that any modern state had to have a single common language: ie, be national.13

Against this SIOC perspective arguments came from the Social Democracy of the Kingdom of Poland and Lithuania led by Rosa Luxemburg and others, and from the Austro-Marxists, Otto Bauer and Karl Renner. In both these cases the fundamental objection is that existing economic integration (of Russian Poland with Russia and German Poland with Germany; of the Austro-Hungarian empire) would be broken up by the creation of new nation-states, leading to economic regression and dominance of the rural classes over the proletariat - a prediction that was borne out in the inter-war period.14

More fundamentally, Parvus (Israel Lazarevich, aka Alexander Gelfand/Helfand) argued in his 1895-96 Neue Zeit series, ‘World market and agrarian crisis’, that the ‘agrarian crisis’ in Germany reflected the unavoidable integration of industrialised Germany into the world market for food supplies - an assessment that has also been confirmed by subsequent research.15 This implied that socialism in a single advanced, industrialised country would also fail, contrary to Kautsky’s argument.

Trotsky’s argument in Results and prospects was narrower. He stated that, on the one hand, the peasantry as a class would inevitably resist the implementation of the proletariat’s policy, so that

… how far can the socialist policy of the working class be applied in the economic conditions of Russia? We can say one thing with certainty - that it will come up against political obstacles much sooner than it will stumble over the technical backwardness of the country. Without the direct state support of the European proletariat the working class of Russia cannot remain in power and convert its temporary domination into a lasting socialistic dictatorship. Of this there cannot for one moment be any doubt (original emphasis).

On the other hand, the revolution in Russia was likely to trigger the European revolution, and “there cannot be any doubt that a socialist revolution in the west will enable us directly to convert the temporary domination of the working class into a socialist dictatorship”.16

Given that the obstacle to SIOC in his view was political, Trotsky was initially (in 1919-20) an advocate of socialist construction under economic autarky - as Richard B Day showed in 1973. After Lenin’s death, however, Trotsky’s arguments in Results and prospects became central targets of his opponents in the succession struggle in the Soviet leadership. His arguments were said to be pessimistic, unrealistic (the Soviet regime had already survived six years) and failing to grasp the smychka worker-peasant alliance. Socialism could be constructed in one country - including the backward former tsarist empire.

In practice, Trotsky was unable to defend the line of Results and prospects - not because it was false,17 but because it appeared inconsistent with the survival of the Soviet state, and thus offered no political hope. (Analogously, to argue openly that the UK is a mere protectorate of the USA and an offshore financial centre with a moderately sized productive economy attached to it, though it is to speak truly, is presently politically impossible in mainstream British politics.) Instead, he produced a series of different criticisms of the economic policies of the successive majorities in the Russian leadership.18

But this still posed the question: why was the Soviet regime, which after the first five-year plan had statised most major production and introduced radical, if ineffective, planification, not an example of ‘socialism’? Trotsky’s answer in the 1936 The revolution betrayed was to argue that it was because socialism had to be a higher-productivity form than capitalism, and because “Socialism is a structure of planned production to the end of the best satisfaction of human needs; otherwise it does not deserve the name of socialism”.19 This amounts to redefining ‘socialism’ as what Marx in the Critique of the Gotha programme called the “higher phase” of communism; and in Trotsky’s appendix on SIOC the same sort of reasoning is used.20

In fact, of course, Trotsky in the bulk of The revolution betrayed goes on to analyse ‘Thermidor’ - that is, that the USSR displayed a dynamic towards capitalism. The bulk of the post-war Trotskyists,21 however, forgot the dynamic aspect of this analysis, treating it merely as more negative grounds to deny that the Soviet regime (and its imitators) were ‘socialist’. At this point we arrive at the point comrade Kennedy started with …

But the problem is that the identification of socialism with the “higher phase” of communism makes it extraordinarily difficult to think through the transition from capitalism to communism. Trotskyists have either, by forgetting the Soviet dynamic towards capitalism, collapsed into left versions of SIOC; or, by treating the regime either as state-capitalist or as a stable non-capitalist exploitative class order, collapsed in the direction of Bakunin’s project of the general strike producing the immediate abolition of the state.

Unclear

Comrade Kennedy’s second paragraph says, as the CPGB does, that “socialism is not another name for communism, and nor is it a mode of production. Socialism is an inherently unstable transitional relation premised on intensive class struggle.” Good.

Instantly, however, we pass to arguments that are at best seriously unclear. “The basis of the latter [class struggle under socialism] is the socialisation of capital and of labour.” What is meant here? Capitalism socialises capital and labour, in the sense that it tends to replace the small household production of peasants and artisans by concentrated/centralised forms of production: that is elementary Marx. Indeed, comrade Kennedy quotes Marx, to precisely this effect: capital socialises production (from Engels’ edition of some of Marx’s 1860s manuscripts as Capital Vol III), making the state ever more clearly “an engine of class despotism” (The civil war in France22).

It is, then, not helpful to say, as comrade Kennedy does, that “The capitalist class is engaged in a struggle to contain this socialisation (emphasis added) by amongst other things utilising, colonising and so corrupting socialism as an economic and political force, with the objective to prevent communism.” The capitalist class struggles for control of the socialised forces of production, in order to hold the working class in subordination and thereby maintain a flow of surplus value.

“Utilising … socialism … to prevent communism” is, as I said earlier in this article, a description of the policy of the US state and its subordinate allies in the cold war - one which has been abandoned since at the latest the fall of the USSR. Comrade Kennedy’s use of this idea, throughout his article, is characterised by a static perception of capitalism (which merely ‘abuses’ socialism in self-defence); and, like the post-war Trotskyists on the USSR and eastern Europe, a static image of China, in which both the persistence of Stalinism and the dynamic towards capitalism - and in the Chinese case towards imperialism - are missing.

Similarly, ‘municipal socialism’ is seen as an ingenious capitalist device for preventing communism, rather than becoming able to play that role only after workers’ organisations themselves promoted it as a means of what were then called ‘palliatives’.

Again, comrade Kennedy sees an original sin of the SPD in the 1875 Gotha Programme, arguing that “The socialism being proposed by SPD leaders was anchored to a top-down bureaucratic, evolutionary transformation of economy, state and society” and that “the SPD programme worked under the assumption that a party of professional socialists would transform the capitalist state into a socialist state”. Given the SPD’s notorious line of “not one man, not one penny for this system”; its illegality between 1878 and 1890; its leaders’ argument that capitalism would collapse in a Zusammenbruch or Kladderadatsch (the target of Bernstein’s polemics); and its active promotion of forms of self-organisation in the localities and in coops, clubs and so on, as well as trade unions, this narrative is flatly false.

Comrade Kennedy says of Marx’s Critique: “The strident, venomous, trenchant and blunt tone of Marx’s critique - usually reserved for the inhuman degradation of capitalism and the ruling class - arises here among fellow socialists because he sees in the programme the hallmarks of class treachery.”

This is la-la land. The normal sharpness of Marx’s polemics “among fellow socialists” is notorious, going back to The poverty of philosophy in 1847-48; Marx equally associated himself with and contributed to the savage polemic of Engels’ Anti-Dühring in 1877.23 The sharpness of the polemic in the Critique of the Gotha programme is not about “hallmarks of class treachery”.

Plus, as Lars T Lih has shown, the programme actually adopted at Gotha (as opposed to the draft Marx and Engels critiqued) did take account of Marx’s and Engels’ comments. And by 1879 Marx was talking about Lassallean verbiage in the Gotha programme as “a compromise having no particular significance”.24

In this context, it is remarkable that comrade Kennedy does not address here Marx’s sharp critique of the Gotha draft for nationalism (quoted above).

Stages

Comrade Kennedy says that socialism is

… not a revolution in stages, with no end in sight, but ongoing phases in the, relatively rapid, revolutionary transformation of society, which will depend more on the international scope of the revolution and the external threats to such a revolution (what we do know is that a one-country or even several-country transformation is unviable and will have similar endings to previous ventures). There is no other reasons as to why the transition should stretch over many decades.

“Stages” is wholly irrelevant: there are few, if any, pre-capitalist societies in the world today, so there is no question of a ‘bourgeois stage’. So far as ‘anti-stagism’ becomes generalised into some sort of philosophical claim, beyond the specific case of the Mensheviks’ argument for a ‘bourgeois stage’ in Russia, it is senseless. It is necessary to turn the electricity off before working on the circuit; to jack up the vehicle before taking a wheel off to replace a tyre; to take down the building before reconstructing its foundations; and so on.

These are necessary stages in the activities in question, and other activities - including social revolution - also involve necessary stages. If Europe (or Britain) tomorrow falls into revolutionary crisis, the result will be the victory of the far right; because, as in fact Trotsky pointed out, the precondition for proletarian revolution is “a party; once more a party; again a party”.25

For comrade Kennedy, the issue is that “the terminology of ‘stages’ opened political possibilities for misapplication, principally, holding out intimations of separate systems in linear time and therefore the possibility of making politics by perpetually kicking the ‘higher’ stage into the long grass and making do with the ‘lower stage’ of ‘socialism’”. This is certainly not Trotsky’s critique of Stalinism in The revolution betrayed, and it remains at a purely ideological level. In fact, distinguishing between ‘stages’ and ‘phases’ fails to yield concrete political tasks alternative to those posited by ‘official communists’.

For the CPGB, in contrast, our critique of the Soviet and similar regimes poses concrete questions of political democracy in institutional forms and procedures for the working class to hold bureaucrats, managers and policemen in subordination, rather than the other way round; and for a continental and global revolutionary perspective, as opposed to SIOC.

SIOC

Comrade Kennedy’s comment that “a one-country or even several-country transformation is unviable and will have similar endings to previous ventures” is correct, though we have to think more carefully about it, and its significance is understated in his article.

The Soviet regime was - contrary to the argument of the Soviet majority in the 1920s - not a single country, but one of the great European empires. It was the military reconquest in 1918-21 of the seceded non-Russian countries (except Poland and the Baltics) that allowed the regime to survive until 1941, and it was gains made in the inter-imperialist war of 1941-45 with US aid that allowed it to create subordinate or imitator regimes elsewhere and to survive from 1945‑89. The effect was dual power on a world scale,26 broken by the fall of the USSR. After that, the dynamic towards capitalism has become increasingly rapid in the remaining former ‘socialist’ countries.

Proletarian revolution in France or Germany could lead to the conquest of the rest of Europe in an international revolutionary war. This, in turn, could produce dual power on a world scale. Proletarian revolution in Greece alone (as various Trotskyists urged on Syriza), or in Britain alone, would be an ephemeral event, meaning no more than proletarian revolution on the Isle of Wight alone - starved out in the very short term.

But, once we recognise that to achieve as much as 1917-21 requires continental-scale action, two points follow. The first is that continental Europe includes substantially larger ‘classic’ petty-proprietor classes (peasants and small businesses) than the UK (which has larger employed middle classes and petty rentiers (private pensioners)). Once we get to revolution in the global south, which is certainly indispensable to achieving more than dual power on a world scale, the importance of small family production is all the greater. The second point is that we have a lot of work to do before we get to the point of the question of power being immediately posed. For both these purposes we need a minimum programme that is consistent with the continued existence of money and the petty-proprietor classes.

Now it may be that the USA will collapse without destroying the world and, with the massive destruction of capital values and debt claims involved, there will emerge a new imperialist order (probably led by continental Europe rather than by China) and a new long boom like the 1950s-60s, leading to a new phase of proletarianisation in the global south, which will change these issues. In reality this looks like a low-probability outcome. The fact that the tendency to proletarianisation in east and south Asia has been accompanied by deindustrialisation and deproletarianisation in the imperialist countries, the Middle East and Latin America, suggests that rather capital will not escape from its dynamic towards world degradation, and the options on the table are international proletarian revolution, generalised nuclear war or general reduction to ‘Somalification’.

In his summary, comrade Kennedy says that “Short of the working class taking power, then socialism, as an unstable transitional relation with a missing pole of communism, will inevitably lead the working class back towards a declining capitalism.”

But what does the working class taking power mean in this context? The nearest approach to a statement in this article is:

Socialism becomes the transition from capitalism to communism under the democratic rule of the working class, through communes and through the state. Which is to say, working class power, exercised through its network of communes and the state, will provide the means through which most of the population will be engaged in some form of administration and management and with the building of democratic control over every sphere of life: ‘the state and politics, work and economy’.

This passage is supported by an endnote citation to the CPGB’s Draft programme, section 5, ‘Transition to communism’.27 Good. But this passage in the Draft programme is written on the basis of the previous overthrow of the state power of the capitalist class. The result of ‘phases, not stages’, then, is that comrade Kennedy appears unable to conceptualise the overthrow of the capitalist state order.

In the third article in this series I will attempt to address the question of transition positively in the light of the negative arguments in last week’s and this article.

-

‘Centuries of Stalinism’ Weekly Worker May 22: weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/1539/centuries-of-stalinism.↩︎

-

See, for example, ‘Dumbness of dumbing down’ Weekly Worker June 29 2003: weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/1449/dumbness-of-dumbing-down.↩︎

-

talkingaboutsocialism.org/differentiating-socialism-and-communism.↩︎

-

Both chapters at www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/1931/tpr/rp-index.htm.↩︎

-

www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1848/communist-manifesto/ch02.htm.↩︎

-

www.marxists.org/history/international/iwma/documents/1864/rules.htm.↩︎

-

Der isolierte sozialistische Staat - abridged in G von Vollmar Reden und Schriften zur Reformpolitik Bonn 1977, pp51-82 (a translation at least of part of it is at deepmarxology.cc/uploads/levellingspirit/Vollmar-Der-isolirte-sozialistische-Staat-English-v1.pdf). See more generally E van Ree, ‘“Socialism in one country” before Stalin: German origins’ Journal of Political Ideologies Vol 15 (2010), pp143-59; and ‘Lenin’s conception of socialism in one country, 1915-17’ Revolutionary Russia Vol 23 (2010), pp159-81; Y Sorochkin, ‘From JG Fichte’s “the closed commercial state” to “socialism in one country”: intellectual origins of Stalinism and Stalinist utopia’ (DPhil thesis, Oxford University 2019): ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:cbc04844-d31f-4d93-8618-814f64668ac1.↩︎

-

www.marxists.org/archive/kautsky/1881/state/3-freesoc.htm.↩︎

-

Translated by B Lewis Critique Vol 37 (2009), pp371-89, and Vol 38 (2010), pp143‑63.↩︎

-

There is a mass of literature on the Second International debate on the national question, but it largely disregards the question of economic integration beyond national borders and the relationship to SIOC. Luxemburg in HB Davis (ed) The national question: selected writings by Rosa Luxemburg (New York NY 1976) is clearer, because more explicitly polemical than Renner or Bauer.↩︎

-

www.marxists.org/deutsch/archiv/parvus/1895/weltmarkt/index.html; A Offer The First World War: an agrarian interpretation Oxford 1991.↩︎

-

My own view - not a CPGB common view - is that Trotsky was right that the peasantry would overthrow the proletarian dictatorship; but because, as Marx argued in The 18th Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, the peasantry cannot rule, but only find a representative-master who will coerce them to produce a surplus for the society, the peasants’ defeat of the proletariat in 1921-29 produces … Stalinism as a form of Bonapartism.↩︎

-

RB Day Leon Trotsky and the politics of economic isolation Cambridge 1973, pp97‑125.↩︎

-

www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/1936/revbet/ch03.htm. “production” is missing in the MIA text.↩︎

-

I leave on one side the issue whether Marx’s two phases of communism represent a correct conception of the transition.↩︎

-

Exceptions are the Spartacists and the Marcyites and neo-Marcyites. The Critique school foresaw collapse of the Soviet regime, but was not strictly Trotskyist.↩︎

-

For some strange reason comrade Kennedy thinks that this from 1871 is “even in [Marx’s] early writings”.↩︎

-

www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1847/poverty-philosophy; www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1877/anti-duhring.↩︎

-

platypus1917.org/2023/06/02/a-review-of-karl-marxs-critique-of-the-gotha-program.↩︎

-

An argument made by the Vern-Ryan tendency in the US SWP in the early 1950s, which has, I think, on the whole been confirmed by subsequent developments.↩︎

-

communistparty.co.uk/draft-programme/5-transition-to-communism.↩︎