01.05.2025

Following the sign of the zigzag

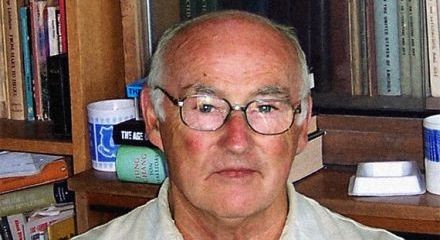

Peter Taaffe died on April 23 2025. While there can be no doubt about his dedication to what he understood by socialism, there was little or nothing consistent, when it came to his strategic ideas. In many ways, argues Jack Conrad, he embodied all that is wrong with today’s confessional sects

Born to working class parents in 1942 Birkenhead, Peter Taaffe instinctively gravitated towards leftwing politics as a teenager. Having joined the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, he soon found himself in the Labour Party. Here he discovered Trotskyism in all its myriad varieties.

Initially, Taaffe hit upon the Socialist Labour League led by Gerry Healy. Understandably he liked neither the man, nor the politics, nor the internal regime. There were not a few other organisations to choose from, but, with Ted Grant and his Revolutionary Socialist League, Taaffe found what he was looking for (the RSL originated in the Revolutionary Communist Party, which broke apart in 1949-50 and was one of the many splits from the so-called Fourth International, then dominated by the likes of Michael Pablo, Ernest Mandel, James Cannon and Pierre Frank).

Taaffe seems to have joined the RSL in 1960. He proved to be a dedicated and tireless worker. Grant provided what he grandly called the intellectual ‘unbroken thread’ with Leon Trotsky and, going back before him, to Vladimir Illich Ulyanov. Taaffe, however, turned Grant’s ideas into a real organisational force. He, was, with good reason, described, as a “brilliant young fellow” by John Baird, a prominent Labour MP and future cabinet minister.1

His comrades say that he had, and never lost, the common touch. A valuable asset. Taaffe could talk to so-called ordinary people in ordinary language about any subject from socialism … but especially to soccer (he was a keen Everton fan).

He could talk to the elite too. In 2012 Taaffe was amongst the speakers at the Oxford Union debating the motion, ‘This house believes that capitalism has failed the poor’. The other speakers supporting the motion were Sir Ronald Cohen, a self-confessed venture capitalist, Michael Brindle QC and a student, Scott Ralston. Each made telling points about various aspects of capitalism’s failures. They wanted, however, to make capitalism work more humanely.

But, of course, Taaffe argued that capitalism had not only failed the poor. It had to be replaced by a socialist system. Amazingly, the motion won the day.2

Clear field

The Grantites found themselves with a clear field in the Labour Party Young Socialists. Formed in 1965, replacing the Young Socialists, by 1967 the Militant Tendency, as it became known, was more or less the sole Trotskyite show in town.

Incidentally the Labour Party bureaucracy has repeatedly closed its youth organisation, following what it regarded as hostile takeovers: 1936, 1940, 1955 and 1964. However, craving respectability, the ‘official communists’, at some point in time (I do not know quite when), rejected the previous policy of keeping recruits within the Labour Party and its youth organisations.

The growing tide of radicalism in the 1960s found its main expression outside the Labour Party. We are talking about the anti-Vietnam war protests, anti-apartheid, student occupations, women’s liberation, youth counterculture, shop steward networks, mass strikes against government attempts to curb trade union power, etc. The Labour Party, with its endless points of order and labyrinthine rules, was off-putting for the majority of those impatient for sweeping change, that is for sure.

The Healyites, the Mandelites, the Cliffites et al found themselves either proscribed or doing far better outside the committee rooms, when it came to gaining recruits. But not the Grantites. They stayed put … and without serious competition they too grew.

In 1964, at the prompting of Sinna Mani, a former member of Healy’s SLL, Grant agreed to the launch of Militant as a monthly for “Labour and socialist youth”. The first issue came out in October, just days before the general election and featured the headline, “Drive out the Tories - but Labour must have socialist policies”. The editor … a young, ready and eager Peter Taaffe.

True, he appears to have had no direct oversight of the first few editions. Arguably that explains why his name was misspelt (with only one ‘f’). Militant was apparently “effectively edited” by Mani, who also served as business manager for a short while.3 He, along with Roger Protz, encouraged different viewpoints and even commissioned articles on mods and rockers, the Beatles and other such high-profile cultural matters of the day.

Either way, the idea of Harold Wilson’s Labour Party adopting “socialist policies” was hard to swallow. Yes, compared with today’s Labour Party, the 1964 election manifesto was wildly leftist, but that is not saying much.

When I came across Militant in the late 1960s and early 1970s as a young member of the Young Communist League (and, unique to my home town, a joint member of the Labour Party Young Socialists), the paper circulated pretty widely, but was, like most left papers then, and today, excruciatingly boring.

These were, remember, the heady days of the so-called underground press, with all sorts of design innovations, psychedelia, avant-garde poetry and established norms and moral boundaries being challenged and crossed (along with plenty of state and rightwing pushback).

Militant was - how should we put it? - well, it was journalistically, politically and theoretically unimaginative, stolid, conservative … in a word, it was economistic to the point of chemical purity. It shunned women’s liberation, the alternative music scene, critical sports commentary, the environment and wanted nothing to do with illegal drug use, let alone bourgeois perversions such as homosexuality. Nor did it take anything but a hostile view of the IRA struggle for Irish reunification. Everything would be put to rights under socialism.

Meanwhile, there was the demand to nationalise the top x, y or z monopolies, electing a Labour government and celebrating the achievements of the Soviet Union and the so-called deformed workers’ states … including Ba’athist Syria. Sputniks, rockets to the moon, economic dynamism, free education and cheap transport, “provides glaring proof of the decadence and impotence of capitalism in our era”.4

Deep entry

During the 1950s more or less the whole gamut of Trotskyism was committed to what they call ‘entry’. Basically that meant going into the Labour Party as a small group and then, after a relatively short time, coming out as a slightly bigger group. That could be excused as a tactic - it was recommended by Leon Trotsky in the mid-1930s. Grant, however, not only considered it a “correct tactic” in the 1930s: he went further with the idea of “total” or “deep entry”.5 This meant a small group going into the Labour Party and staying in with the intention of transforming the host body. Taaffe thoroughly internalised “deep entryism” … well, till the 1990s.

Lenin, of course, famously sided with those who called for the newly formed CPGB to seek affiliation to the Labour Party: a party of the Second International, from which he was doing his utmost to lever away the communist and revolutionary forces in order to win them to the banner of the Third International.

There is, though, a world of difference between Lenin’s affiliation tactic and deep entryism. Wanting the CPGB to affiliate to the Labour Party did not mean fostering illusions. ‘Deep entry’ does … if the entryist adapts politically to the host.

Lenin called Labour a “bourgeois workers’ party”, which “exists to systematically dupe the workers”.6 However, given the small size of the CPGB and the strength of Labourism, it was vital to open up an active dialogue within the working class between the advanced, communist minority and the Labourite majority. If the CPGB was unable to do this and establish close links with the mass of workers, “then it is not a party, and is worthless in general” (Lenin).7

What made the ‘British exceptionalist’ affiliation tactic viable was Labour’s federal structure. Before 1918 it was not a party in any full sense of the term; membership came through its affiliated trade unions or cooperative or socialist societies. After 1918, the Labour Party rules made provision for individual membership.

As far as Lenin was concerned, CPGB affiliation to the Labour Party would give the communists a far wider audience; indeed affiliation could only have been the result of successful communist mass work in the trade unions and Labour Party wards and constituencies. On the other hand, if the CPGB was turned down, Lenin said that “we shall gain more, for we shall at once have shown the masses that [the Labour Party leaders - JC] prefer their close relations with the capitalists to the unity of all the workers”.

The affiliation tactic demanded, as a matter of elementary principle, that the CPGB would have “full freedom of criticism” and be “able to conduct its own policy”. The CPGB would openly declare it would support the Labour Party leadership like a “rope supports a hanged man”.8

Militant Tendency, at least in private, liked to draw a direct correspondence between Lenin’s 1920 tactic and its strategy of deep entryism. It circulated Grant’s 1959 Problems of entryism9 to new recruits, but in public its members behaved like chameleons, taking on the colours of left reformism. In point of fact, deep entryism was extended internationally to the parties of social democracy - and even to out-and-out bourgeois parties: eg, the Pakistan People’s Party.

What passed for programme was written by Taaffe himself. Militant: what we stand for is a slightly more left, but also more Labourite, version of the ‘official’ CPGB’s British road to socialism programme (for my 1991 critique see Which road?10).

Its socialism would result from an enabling act passed through the House of Commons by a Labour majority. The monarchy, the Lords, MI5, the army, the courts, etc are all easily overcome and Britain thereby becomes a shining beacon of progress and prosperity that people abroad will admire, envy and rush to emulate. Blockade, sanctions, counterrevolutionary civil war - all of that is brushed aside with hardly a thought.

To justify this touching perspective, Taaffe had to concoct and dissemble. For example, the treachery, strikebreaking and imperialist warmongering of the Labour Party, the reason why it has historically operated as a “second eleven of capitalism”, was, according to Taaffe, because the right wing had “infiltrated the labour movement”. And Militant Tendency alone represented the continuation of an original Marxist strand in the Labour Party. “Marxism”, maintained Taaffe, “has always been part, and an important part at that, of the Labour Party right from its inception”.11

Obviously, Taaffe was attempting to turn the rhetorical tables on the right. Fair enough. But it made bad history, which, when all is said and done, amounts to a gross distortion of the facts. Neither the implication that Militant Tendency somehow dates back to the origins of the Labour Party nor the idea that the Labour Party has some sort of Marxist ancestry (if not from both parents, then at least from one) stands up to serious examination.

When the Labour Party was established in 1900, it is true that the Social Democratic Federation counted as an affiliate. Two executive committee seats were allocated to it. But the SDF almost instantly walked. Later, in 1916, the British Socialist Party, the organised continuation of the SDF, affiliated and went on to provide the bulk of the newly formed CPGB in 1920. However, its affiliation bid was rejected by one Labour conference after another. More than that, the CPGB was proscribed and individual communists were hounded out and barred from membership by rule.

No, the actual Labour Party was conceived in the bowels of the TUC and became a serious parliamentary force through the recruitment of a bevy of trade union-financed Lib-Lab MPs (ie, in the official lingo, “men sympathetic with the aims and demands of the labour movement”12). It was the TUC and Lib-Lab MPs who were the mother and father of Labourism. There was no rightwing “infiltration”: the right dominated the Labour Party from the very start.

Success and failure

Of course, for the Grantites the main focus was the routine of LPYS meetings, LP conferences and directing trade union struggles into the Labour Party. And by 1970 they found their reward by gaining more or less full control over the LPYS.

This gave them a seat on the Labour national executive committee and, with the LPYS acting as a conveyer belt into the Labour Party, greater and greater influence in wards and constituencies followed. Membership grew to the thousands and not only did Militant go weekly, feature a red masthead and increase from four, to eight, then 12 and finally, in January 1979, to 16 pages … there was a sophisticated apparatus with many (perhaps 130) full timers, a print shop and an extensive headquarters - first in Bethnal Green, then Hackney Wick, then Leytonstone. There were too regional offices in Birmingham, Liverpool and Newcastle. The man in charge of the whole operation … general secretary Peter Taaffe.

Because of its objectively modest, but real, success, Militant Tendency became a favourite target of a frothing, but altogether cynical, rightwing press campaign, designed to weaken Labour’s electoral chances. Therefore Militant became a target of the Labour right ... and therefore the soft left (ie, Michael Foot).

Defiant, Militant Tendency staged the 2,600-strong ‘Fight the Tories, not the Socialists’ rally at Wembley conference centre. And, despite the media baying, the comrades managed to get Pat Wall, Dave Nellist and Terry Fields elected as Labour MPs in 1983 and take the lead, when it came to Liverpool council (Derek Hatton was elected deputy leader). The high point of Militant Tendency’s fortunes.

Liverpool council set a deficit budget, which included declaring 31,000 council workers redundant. The idea was to buy the time needed to negotiate a deal with Margret Thatcher’s government. There was never the intention of sacking anyone. But the tactic backfired spectacularly. Rank-and-file trade unionists rebelled, national officials expressed outrage and Labour Party HQ seized upon it as a stick with which to beat Militant. The stage was set for Labour leader Neil Kinnock to lambast Militant Tendency at the 1985 conference for “the grotesque chaos of a Labour council - a Labour council - hiring taxis to scuttle round a city handing out redundancy notices to its own workers”.13

Labour’s NEC suspended Liverpool Labour Party in 1986. Derek Hatton believes that “Peter Taaffe and the rest of Militant” were tactically wrong to “knuckle under” to Kinnock.14 The witch-hunt was never going to stop with Liverpool. And so it proved.

After a couple of years of internal constitutional wranglings and legal challenges, Militant’s five-strong editorial board, including Ted Grant and Peter Taaffe, were expelled. More expulsions inevitably followed. But not that many. Perhaps 200, perhaps a few less. The biggest blow for Militant Tendency was, though, the effective closure of the LPYS as a campaigning organisation in 1987.

Poll tax

However, a new lease of life came with mass opposition to the poll tax. Imposed in Scotland a year before the rest of the country, with other sections of the left dithering, Militant took the initiative.

A Glasgow conference in April 1988 agreed to non-payment and forming a network of local anti-poll tax unions. Militant’s Tommy Sheridan was the public face. When the poll tax went national, Militant retained its tight organisational grip. Many thousands refused to pay and many were jailed. In May 1990, a riot erupted in Trafalgar Square … denounced by Militant. Disgracefully there was even talk of naming names. Either way, there can be no doubt that the poll tax was one of the factors contributing to the fall of Margaret Thatcher in November 1990 (the other was, of course, Europe).

Here, though, were the seeds of the coming split between Grant and Taaffe. Grant thought it would be tactically astute to have MPs who supported Militant Tendency pay their poll tax - not so as to avoid prison, but to keep their Labour Party cards (Kinnock had insisted that no Labour MP should defy the law). Taaffe won the argument. How could MPs call upon millions not to pay, when they themselves paid in order to remain in the Parliamentary Labour Party? Terry Fields MP went to prison and was expelled.

Grant was determined to weather the storm. He was convinced that the working class antagonism to capitalism was inevitable (true) and that that antagonism would inevitably find itself channelled into, and expressed by, a Labour Party that would inevitably move more and more left to the point of revolution (untrue).

He stuck like a limpet to that much quoted line in the Communist manifesto: “The communists do not form a separate party opposed to the other working class parties”15 - weirdly interpreted as a timeless instruction issued by Marx and Engels for communists not to organise outside the Labour Party. A formulation dumbly repeated by Grant’s present-day successors, Alan Wood and Rob Sewell … till, that is 2024 and their born-again Revolutionary Communist Party.

Taaffe came round to the view that the time was overdue for organising outside the Labour Party. Apparently, he would ask his comrades, “What would Trotsky do in this situation?” He felt Trotsky would have been severely critical of Militant Tendency for not launching an ‘open turn’ at the height of the poll tax movement or even earlier, when it was driven out from the Labour Party in Liverpool (basically Hatton’s position).

Militant fielded Lesley Mahmood against the official Labour candidate, Peter Kilfoyle, in the July 1991 Liverpool Walton by-election. Our position at the time was quite clear. This was more than an internal Labour Party squabble. We opposed those sectarians who called for a ‘plague on both houses’ boycott and the soft left, Trotskyite and Communist Party of Britain and New Communist Party ‘official communists’ who lined up behind the bosses’ second eleven.

Instead we urged all partisans of the working class to support comrade Mahmood: a victory for her would be a “victory for struggle over passivity, a victory for those who call themselves socialists against the explicitly pro-capitalist policies of the Labour Party, a victory of the future over the past.”16

Of course, we could not give Mahmood and Liverpool Real Labour anything other than critical support. We wanted to see Mahmood win in order to show those who supported her that we need go further. Unfortunately Mahmood lost … and lost badly.

Nevertheless, because Militant had broken from its programme, it found itself strategically adrift. Taaffe’s What we stand for was useless as any sort of a guide to action now. Some of its leaders wanted to backtrack. They wanted members to keep their heads down in the Labour wards and hope for better times. For them the 2,613 votes in Walton was no “pointer to the future”. Rather it was a dire warning that the whole 40-year deep-entryist project was about to be wrecked. The majority disagreed. They want to generalise from Walton.

Militant’s central committee split 46:3 over the question. In numerical terms a minority of three is nothing. But they were not any old three. They consisted of the grand old man, Ted Grant himself, Rob Sewell, national organiser and Alan Woods, editor of Militant International Review. They were prepared to remain silent as long as Walton was a one-off. When it became clear that the majority had no such intention, they went public.

In a document leaked to The Guardian, the three made clear their opposition to Militant Tendency’s open turn, describing it as “ultra-left adventurism”.17 They argued that, with the “active base of the Tendency in Britain and internationally” shrinking, Kinnock’s purge and a general downturn on the left means that there are “objective difficulties” for Militant, that now is the time to retreat not attack.

The argument got bitter and personal too. The minority complained of a “clique” (ie, the majority headed by Taaffe), operating “outside formal structure of the Tendency”, which has attempted to shield “individuals from criticism” and “gag” dissidents. The majority implied that Grant was getting crusty, if not senile; that, with Labour’s shift to the right, a vacuum existed on the left: “It would be criminal to pass over an immediate opportunity for expansion in order that we may cling to our few remaining points of support within the Labour Party.”18 Optimism on steroids.

Remember, Taaffe dismissed any notion, any idea of a return of capitalism in eastern Europe and the Soviet Union as a “chimera”19. Even as it was happening, he naively welcomed the prospect of the “red 90s”.20 Our assessment was rather more realistic and sober-minded. We warned of crashing living standards in the east and the reaction sui generis in the west. Capitalism would be triumphant, the working class badly weakened and the idea of socialism consigned to the lunatic fringe … but the surviving, considerably shrunken, thoroughly disorientated left would likely not suffer harsh repression.21

After Labour

Taaffe took the lead in forming first Militant Labour, then, in 1997, the unfortunately named Socialist Party in England and Wales. He served as general secretary till 2020, before handing over to his chosen heir and successor, Hannah Sell … so he lives on with her modest talents, a much reduced membership and a weekly paper, The Socialist, that makes Militant look positively interesting.

Taaffe declared Labour dead for the working class and the struggle for socialism. Under Tony Blair, especially with the dumping of the old Fabian clause four, he insisted that it had morphed into something essentially no different from the US Democrats. In his words, Labour “has been bourgeoisified and is now a capitalist party”.22

We actually worked closely with SPEW in the Socialist Alliance. They established it as some sort of loose alternative to Arthur Scargill’s Socialist Labour Party. We took the initiative and set up the London Socialist Alliance and it was from this salient that we succeeded in bringing the Socialist Workers Party, then under John Rees, onboard. The Socialist Alliance took off with 98 candidates in the 2001 general election and showed some considerable promise.

As one of the six principal supporting organisations, we envisaged unity in a Socialist Alliance Party based on the solid foundations of a communist programme.23 Not the SWP, not SPEW. The general election manifesto which they pushed through was entirely within the economistic frame - democratic demands hardly featured and the necessity of a revolutionary break with capitalism was glaringly absent.

The SWP hankered after a popular front and soon dumped the SA for Respect. As for SPEW, Taaffe could not live with the SWP’s majority in the SA. Instead of courting allies, upgrading its ideas, fighting to become a majority, SPEW desperately sought excuses to split. Strategically it opted for a Labour Party mark two in the form of the Trade Unionist and Socialist Alliance - a hopeless Labour Party mark two project. Hopeless because the Labour Party mark one still exists, still has a majority of trade unionists affiliated to it and still commands the votes of most class-conscious workers.

Nonetheless, Taaffe found vindication in the Blair, Brown and Miliband leaderships - supposedly fundamentally different to Wilson, Callaghan and Kinnock. But then the heavens fell in. Jeremy Corbyn surprisingly got onto the leadership ballot and unsurprisingly won by a landslide victory a few months later in September 2015. He got 59.5% of the first-preference votes. Labour membership surged to 550,000 and the bourgeois establishment trembled.

Humbled, humiliated and discombobulated Taaffe eventually felt compelled to write to Labour’s new general secretary, Jennie Formby. His letter, dated April 6 2018, begged for a meeting that would “discuss the possibility of our becoming an affiliate”.24 As must have been expected, she flatly rebuffed his overtures … citing Tusc election contests. But had Labour suddenly remorphed into a bourgeois workers’ party? Had Taaffe been wrong in his previous assessment? He never said. What we do know is that he sighed with relief when Formby’s ‘thanks, but no thanks’ reply came through.

Taking SPEW’s membership back into ‘deep entryism’ would have risked losing everything organisationally. There would have been resignations and rebellions. Complaints of being taken for a ride. Taaffe bottled it and battened down. SPEW proved itself to be politically “worthless in general”.25 More than a pity.

However, SPEW not only declined to involve itself in the class war being fought over the Corbyn leadership. Effectively it sabotaged our side. Attempts to affiliate, or reaffiliate, trade unions such as RMT, the FBU and PCS found SPEW members arguing for unions to save their money and remain politically independent, so as to pick and choose alternative candidates … the traditional line of the ‘non-political’ pro-capitalist right. Taaffe must have been responsible. It amounted to scabbing! Not that the SWP was any different. Narrowly conceived sect interests always came first.

The Grantites took much pleasure in SPEW’s failure, the failure of Tusc and the failure of the affiliation talks letter. Of course, with the election of Sir Keir Starmer and the witch-hunt reaching new heights, comrades Woods and Sewell took their own ‘open turn’ and soon adopted a Trotskyist form of third-period politics. Out went the old ‘elect Labour on a socialist programme’ Socialist Appeal, in came the new ‘are you a communist’ RCP. Members are now promised the collapse of capitalism and a full-blown revolution within five or six years … led by the RCP (Labour has completely disappeared from the radar as a site of struggle26).

As for Taaffe, freed from the confines of the Labour Party, and without Grant to hold him back, he allowed his members to discard the old workerist certainties and chase after this, that and the other fad. Everything was predicated on organisational growth … a surefire road to disaster. In Scotland his comrades not only formed the Scottish Socialist Party … they split and went full left-nationalist. It was essentially the same with #MeToo feminism and the whole rainbow array of identity politics ... Taaffe must have concluded that things were in danger of spiralling out of control.

Eventually this triggered the ruinous schism in the Committee for a Workers’ International (founded in 1974 by Militant and with some 45 national affiliates at peak success). Beginning, in November 2018, with a rather strange dispute on its executive over a phone hacking scandal in the top-heavy Irish section, things quickly went from a crack to a chasm. Within a few days there were proclamations of “fundamental differences” and the creation of a minority faction headed by Taaffe, the wonderfully named ‘In Defence of a Working Class Trotskyist CWI’ faction. Split produced splits and the splits themselves proceeded to split to the point of atomised sects of threes, twos and ones. Note the fate of Socialist Alternative in the UK.

If truth were told, finding himself in a 23:21 minority on the International Executive Committee was completely unacceptable, as far as Taaffe was concerned. Rather than waiting for the CWI’s world congress, due in January 2020, he simply refused to accept the result.

Arguing, rightly, that compared with SPEW, the other sections in this oil slick international amounted to a diddly squat, he proceeded to expel, anathematise and marginalise. True, Russia with its 25 members had two representatives on the IEC. Greece with 302 members had four. Yet SPEW, at the time, claimed a couple of thousand members. It too, however, had four IEC members. But this arrangement was arrived at, in the beginning, with Taaffe’s full blessing, agreement and calculated reckoning.

Clearly he regarded both SPEW and the CWI as his private property. A sad coda for his 65 years in organised left politics l

-

M Crick Militant London 1984, p45.↩︎

-

The Socialist February 18 2012.↩︎

-

M Crick Militant London 1984, p47. Mani went on to be Labour mayor of Lewisham between 1993 and 1994 - after which, in 2001, he joined the Green Party.↩︎

-

R Silverman and T Grant Bureaucratic or workers’ power London 1982, p27.↩︎

-

VI Lenin CW Vol 31, Moscow 1977, p258.↩︎

-

Ibid p238.↩︎

-

Ibid p88.↩︎

-

J Conrad Which road London 1991 - communistparty.co.uk/resources/library/jack-conrad.↩︎

-

P Taaffe Militant: what we stand for London 1990, p29.↩︎

-

‘Report of the Conference of Labour Representation’ London 1900, p11. These men, writes Ralph Miliband, were “in the main” … racial Liberals, either explicitly hostile to, or with very little sympathy for socialism in any of its variants” (R Miliband Parliamentary socialism Pontypool 2009, p17).↩︎

-

D Hatton Inside left: the story so far … London 1988, p102.↩︎

-

Ibid p173.↩︎

-

K Marx and F Engels CW Vol 6 New York NY, p497.↩︎

-

Provisional Central Committee statement The Leninist June 28 1991.↩︎

-

The Guardian September 3 1991.↩︎

-

The Guardian September 6 1991.↩︎

-

Militant July 21 1989.↩︎

-

Militant January 19 1990.↩︎

-

See J Conrad From October to August London 1992 - communistparty.co.uk/resources/library/jack-conrad.↩︎

-

P Taaffe Socialism and left unity: a critique of the Socialist Workers Party London 2008, p42.↩︎

-

Our CPGB Draft programme - suitably edited naturally.↩︎

-

The Socialist September 19 2018.↩︎

-

VI Lenin CW Vol 31, Moscow 1977, p238.↩︎

-

Searching the RCP’s website, the latest article turning up with a ‘Labour Party’ is written by Rob Sewell … in July 2021! Here he made this hostage-to-fortune promise: “We will not change our orientation towards the mass organisations, the Labour Party, or the trade unions, in which the class struggle will sooner or later find its expression. Whatever the right wing does, there is no way that Marxism can be separated from the Labour movement. Of course, we will not adopt a sectarian attitude. History is littered with the wreckage of small sectarian groups, who have attempted to mould the workers’ movement around their preconceived plans, and have failed” (‘Marxism, the Labour Party, and the witch-hunt’ Socialist Appeal July 23 2021). And yet, scrolling down the main webpage, we find plenty of attacks on Labour, including those equating Labour with Reform and the Tories, and denying that “Labour is a ‘lesser evil’ in upcoming elections” (M Hogan ‘Is Labour any better than Reform and the Tories on migration?’ The Communist April 24 2025). So when did the qualitative change happen? When Socialist Appeal, along with Labour Party Marxists and Labour Against the Witchhunt, was proscribed? Hardly credible.↩︎