20.03.2025

Saluting those who went before

There were plenty of illusions, but there can be no disguising the courage. Yassamine Mather pays tribute to the women who took up the cause of the working class and fought for revolution

Last week I gave a talk about the women of the Iranian left - partly because in the ‘Woman, life, freedom’ protests of 2023 the struggles and role of these women were rarely mentioned, undermining their history.

The younger generation seems unaware of the courage and the sacrifices of those who paved the way for the women’s movement in Iran. Some have illusions about the superficial aspects of unveiling during the Pahlavi dynasty, not knowing that this only affected a minority of middle class and upper class women in urban areas, and that dozens of leftwing female activists were imprisoned or killed for their political activities by the same regime.

So this article is an attempt to put the record straight.

I am going to start with Maryam Firouz (or Maryam Farman Farmaian). I have previously written extensively against the Tudeh (‘official communist’) Party. However, its women’s association, the Democratic Organisation of Iranian Women, led by Firouz, did play a significant role when it came to the struggle for women’s emancipation. The origins of this movement go back to 1943, marked by the establishment of two key groups: the Women’s Organisation for party members and the Women’s Society for Party Supporters.

In 1949, these two entities were merged into a single organisation known as the Society of Democratic Women. It should be noted that the leadership of these groups was often comprised of women who were related to prominent party figures. Still, many were also distinguished by their own professional achievements or active involvement in the early women’s movement. Notable figures included Zahra and Taj Iskandari, Maryam Firouz, Khadijeh Keshavarz, Akhtar Kambakhsh, Badri al-Monir Alavi and Aliyeh Sharmini - some of whom had been associated with the Patriotic Women’s Society, an initiative launched by the Socialist Party.

The Women’s Organisation of Tudeh primarily focused on engaging students, teachers and other urban-educated women, as well as women working in factories and offices. It was focused on women’s rights, including suffrage, education, employment and social opportunities.

Maryam Firouz: She was born into an aristocratic family in Iran and, despite her privileged position, became involved in progressive politics, breaking away from the expectations of her social class. She is also known as the ‘Red Princess’, as she was a direct descendant of the Qajar dynasty.

It was when she was a student in Europe that she became a communist. Tudeh had a very problematic history, before and after the revolution of 1979, with inconsistent positions when it came to Mohammad Reza Shah’s rule, and it often mirrored the USSR’s changing attitudes to the late shah. However, what distinguishes Firouz is her activities in organising the democratic organisation of women in Iran.

Of course, as part of the political bureau and the central committee, she was responsible for Tudeh’s support for the Islamic Republic after 1979 - only to be arrested herself, once they were no longer of any use to the new regime. Following torture in prison, the leadership of Tudeh appeared on various TV programmes to denounce their politics and their history. However, Maryam Firouz was the only member of the leadership who refused to appear in these humiliating events, even though she most probably faced the same kind of pressure - and torture - as anyone else.

Vida Hajebi Tabrizi: She is the second one who is definitely worth highlighting. Born in Tehran, she pursued her studies in architecture in Paris during the 1950s, and she was a friend of Farah Diba (later the wife of the shah). Of course, they fell out and if you read what Hajebi Tabrizi wrote about her life, she adds that she protested against Diba’s visit to France, years later. Hajebi Tabrizi was married to a Venezuelan socialist, Osvaldo Barreto, and moved to Venezuela, where she worked with the Venezuelan Communist Party and participated in their guerrilla activities. She later returned to Iran, where she worked at the Institute of Social Science Studies.

Her activities led to her first imprisonment in July 1972, and she endured appalling treatment during that time. Her plight drew international attention, with Amnesty naming her Prisoner of the Year in 1978. She was released just before the Islamic-led revolution in early 1979.

After the revolution, in exile, she wrote valid articles criticising armed struggle and she became involved in a journal, Left Wing, in collaboration with author Nasser Mohajer. She also wrote a book about the experience of women political prisoners, called Dade Bidad.

Pouran Bazargan: Pouran was born into a devoutly religious family that barred her from attending high school after the ninth grade. In her own words:

After enduring years of confinement at home, I pursued education independently, completed high school, and even earned a university degree. My academic record was exceptional. My time at Mashad University in Iran (1960-63) coincided with a surge in social and political activism, prompting me to join the movement. As one of the few female political activists at the time, I faced persecution by Savak, the shah’s brutal security apparatus, which only deepened my commitment to the struggle for freedom and democracy. Though I initially framed my activism as resisting patriarchy and defending human dignity, I soon became part of a broader wave challenging state censorship and oppression. My comrades were many; we could not remain indifferent to the suffering around us. Politics, we believed, would inevitably shape our destinies - the question was not ‘why’, but ‘how’ to engage.

Influenced by the religious, reformist culture surrounding me, I co-founded the Islamic Association of Women in Mashad. My colleagues included young women from politically active families - some with relatives executed by the regime, others even identifying as communists. Five members of my own family were killed in these struggles.

Later, while pursuing a master’s degree in Tehran and working as a high school teacher, I connected with individuals who would establish the People’s Mojahedin Organisation of Iran. My brother, Mansour, affiliated with the group, and facilitated my introduction.

Though I learned much from them, I refused uncritical adherence, even questioning Islamic dogma. For instance, I challenged a comrade’s interpretation of Quran 23:6, which permits men to exploit enslaved women sexually. His justifications rang hollow.

The Mojahedin, like many political movements, selectively invoked scripture to suit their aims - a tactic mirrored today by the Islamic Republic. Yet on women’s issues I insisted on autonomy - a stance that clashed with the organisation’s hierarchy ...

In 1969, in Rafa, I married Mohammad Hanif Nejad, a Mojahedin founder. Revolutionary demands left no room for traditional private life; our existence was subordinated to the struggle against dictatorship.1

Her account counters the claim that Marxism infiltrated the Mojahedin-e-Khalq via ‘entryism’ - allegedly a strategy where Marxists covertly take over religious groups. Instead, her writings reveal authentic ideological evolution among members. They also highlight the Iranian left’s internationalist ethos.

Following her husband’s execution in 1973, Pouran recounts:

I went underground for over a year, striving to sustain the armed resistance against the regime and its imperialist backers. By August 1974, I relocated abroad, joining the Mojahedin’s international branch in Iraq. My work with the Palestinian movement began then - I served at a Red Crescent hospital in Damascus and later in Beirut’s Sabra refugee camp during Lebanon’s civil war. Those years with resilient, oppressed communities were among my most fulfilling.

Assigned to Turkey, I laboured in sweatshops and hotels, while covertly smuggling arms into Iran. As our organisation matured politically and militarily, we critically re-evaluated our religious ideology, ultimately embracing Marxism. While the leadership formally announced this shift, many members, myself included, had already gravitated toward Marxist principles. However, the clandestine nature of guerrilla struggle - where information and debate were restricted - enabled problematic methods during this transition. These errors, though irreparable, cannot negate the revolutionary imperative to break from religious dogma.

Killed before 1979

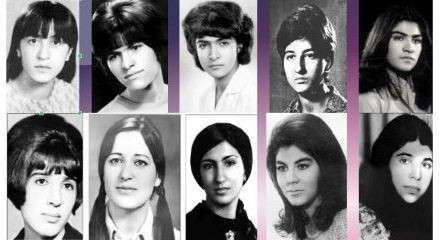

Fedayeen women killed before 1979 include Fatemeh Nahani, Afsar Sadat Hosseini, Pouran Yadollahi, Mehrnoush Ebrahimi, Asmar Azari, Sepideh Sharif, Saba Bijhanzadeh, Marzieh Ahmadi Oskoui, Zahra AghaNabi and Fatemeh Rokhbin.

The life story of every one of these women - and many more not listed here - is an example of bravery, political dedication, commitment to Marxist ideals and internationalism. For brevity, I will concentrate on just two of them.

Pouran Yadollahi (when I went to Kurdistan I chose her name as my cadre name): A member of the Iranian People’s Fedai Guerrillas, was born in 1950 in Isfahan. Due to her father’s occupation, she spent her childhood in Abadan. Her father, an oil company worker and a politically conscious worker, played an active role in the oil company strikes during that period. Following the UK-US organised coup of August 19 1953, her father was arrested and imprisoned due to his ties with Tudeh. After his release, he was dismissed from the oil company and resettled with his family in a village.

Rural life allowed Pouran to witness first-hand the poverty and suffering of villagers. Growing up in a working class, politically engaged family, she developed political awareness from a young age, gaining insight into the root causes of mass poverty and the anti-people nature of the shah’s regime. The class inequalities she observed daily in society deeply pained her.

After some time in the countryside, the family moved to Tehran. There, during her fourth year of high school, Pouran delivered a conference presentation on history, defying the conventional approach by analysing events through a scientific and materialist lens. She defended the oppressed as the true makers of history and condemned the exploitation practiced by the ruling classes. News of this reached Savak, which interrogated her and her father, forcing him to pledge to curb her “subversive” activities.

In June 1968, Pouran completed high school and passed the university entrance exam, enrolling at the University of Tehran’s prestigious faculty of technology. The politically charged environment on the campus resonated with her militant spirit, and she forefronted student protests. Born into a working class family and eager to study Marxism, she immersed herself in the world view of the working class.

The Siahkal uprising (1970) opened new horizons. She broke from the narrow confines of trade union politics and came to see armed struggle as the path to liberation. In 1971, Pouran joined the Fedayeen-e-Khalq guerrillas, determined to shatter what the organisation called the “cemetery silence” imposed by the shah’s regime.

She was sent to Mashad with Behrouz Abdi to establish a branch, where they planned an operation to expose the shah’s reactionary policies on the anniversary of the so-called ‘White Revolution’. However, on February 3 1972, a bomb they were preparing detonated prematurely at their base. Behrouz was killed and Pouran was critically injured. En route to the hospital, she took cyanide to avoid capture. Despite the regime’s efforts to revive her, she died three days later.

In a 1973 biography, the organisation wrote: “Comrade Pouran proved, in her final moments, that her faith in the working class’s cause was so profound that she chose death over betraying the people’s secrets.”

Marzieh Ahmadi Oskouei: She was born in March 1945 in a suburb of Tabriz. Her friends affectionately called her “Marzieh Jan” (‘Dear Marzieh’) and later “Marjan”. Comrade Marzieh was a poet, writer, teacher, leftwing political activist, organiser of the student movement and a member of the Iranian People’s Fedai Guerrillas during the Pahlavi regime. She lost her life at the age of 29 in April 1974 during a clash with Savak agents in Tehran.

She completed her primary and secondary education in Osku and Tabriz, then enrolled at Tehran Teacher Training College to continue her studies. She was one of the organisers of the college teachers’ strike in 1970. During her student activism, she was arrested and sentenced to one year in prison. In 1973, she joined the Democratic People’s Front, a group preparing for armed struggle. Among prominent members of the Front were Mostafa Shoaiyan and Nader Shaygan Shami Asbi. She became a member of the People’s Fedai Guerrillas the same year.

According to all who knew or encountered Marzieh Ahmadi Oskouei, she was an elegant woman, dressed in stylish coats and skirts - with long, braided hair that lent her a distinctive grace and beauty. Generous and warm-hearted, she shared everything she had with her comrades. She had a deep knowledge of theatre, film and literature, and tirelessly sought out the finest works, frequenting intellectual circles. Simultaneously, she organised lectures for her politically conscious friends. During her years at teacher training college, she served as a student representative. Initially representing female students, her exceptional capabilities led all students to recognise her as the best candidate to hold the responsibility of representing them.

She was one of the leaders and organisers of the student hunger strike in March 1971 at the Sepah-e Danesh Higher Teacher Training College. The hunger strike was held to demand the release of two arrested students and ultimately succeeded in securing their freedom. While she was negotiating in the university president’s office, news spread outside that Marjan had been arrested by Savak. Some of her comrades swiftly surrounded the building where she was being held and managed to gain her release.

Killed since 1979

Activist women executed or killed since 1979 include Zahra Behkish, Nastaran, Ashraf Ahmadi and Roghiyeh Akbari Monfared.

Zahra Behkish (Ashraf): She was born in 1946 and after completing her secondary education she studied physics at university and then began teaching at high-school level.

Comrade Ashraf was banned from teaching because of her opposition to the Pahlavi regime. After contacting the Iranian People’s Fedai, she joined this organisation and went into hiding.

After the February revolution in 1979, she worked in the organisation’s publications department and, following the split between a minority and the majority of the organisation, Ashraf joined the minority faction and was in charge of the district committee (incidentally, the minority were a minority on the central committee, but a majority when it came to the membership). I met her briefly in Kurdistan, where she had come from Tehran to discuss and prepare her plans for future activities.

In the early hours of September 2 1983, the residence of comrade Zahra Behkish in Tehran was surrounded by the Islamic Revolutionary Guards and she was arrested. At the moment of her arrest, she tried to swallow her cyanide tablet, so that she would not fall into the hands of the regime’s security forces. However, sources have confirmed that the Revolutionary Guards were able to get her to the hospital in time. She was subsequently imprisoned and tortured. The authorities wanted to obtain information from her. However, she died after a few days, keeping the organisation’s secrets safe.

Executed in 1988

In the summer of 1988, shortly after the end of the Iran-Iraq war, supreme leader ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini issued orders for the mass execution of thousands of political prisoners. Lasting around five months from July onward, these killings occurred nationwide and spanned at least 32 cities, conducted without judicial oversight. Trials, where they occurred, ignored due process and made no effort to assess guilt or innocence.

Reports indicate widespread torture of prisoners during this period, while authorities systematically concealed the scale and details of the executions. Although the exact death toll remains uncertain, human rights organisations estimate that up to 5,000 individuals were executed, amongst them many leftwing and Muslim women, including members and supporters of Mojahedin-e-Khalq. These executions were just mindless revenge - the excuse was the Mojahedin’s military incursion into western Iran in the final stages of the war with Iraq, which was eventually defeated by the Iranian military.

A large proportion of those executed were members and supporters of leftwing organisations and had nothing to do with the Mojahedin, but, even in the case of those associated with the Mojahedin, they had nothing to do with this military operation, as they were serving long prison sentences.

While celebrating the life of Fedai women, who will remain symbols of resistance and heroism, especially in the era of individualistic, neoliberal feminism, the Iranian guerrilla left was ultimately an extreme form of activism - hopelessly outmanoeuvred, when it came to the reality of revolution in Iran.

-

transcribed from video and translated by Yassamine Mather (March 2025).↩︎