13.03.2025

A century of illusions

Royalist fortunes hinge on Donald Trump, but also on promoting the personality cult of Reza Khan. Yassamine Mather looks at the rise and fall of a mountebank

Donald Trump signed an executive order on January 20 2025 suspending US foreign development aid for 90 days to reassess its alignment with his ‘America First’ agenda. The state department promptly froze most foreign aid programmes.

However, leaked documents from September 2024 suggest that US aid was deeply tied to efforts to engineer regime change in Iran. The documents, obtained by The Grayzone reveal a covert initiative led by Carl Gershman, former director of the National Endowment for Democracy, to form an Iran Freedom Coalition, comprising key opposition figures such as Reza Pahlavi, son of the former shah.1 The NED, historically linked to US intelligence operations, has been involved in funding opposition movements globally under the guise of the promotion of democracy.

Trump’s aid freeze disrupted this longstanding strategy, and the panicked response from some of those parading as human rights activists and defenders of press freedom suggests complete dependence on US financial support, raising questions about the true nature of these groups. As Trump’s review continues, the various contenders of ‘regime change from above’ are witnessing nasty battles between royalists and the supporters of Mojahedin-e-Khalq over who will remain the ‘favourite’ group for regime change.

I have already written about MEK,2 but this article deals with Iran’s royalists, who unfortunately have made some progress in the last few years by presenting a completely distorted history of the Pahlavi era. Two TV stations, both paid by Zionists, have used 24/7 broadcasts of old film reels to create a level of nostalgia for the ancien régime. These mainly show the upper middle classes and the aristocracy enjoying a relaxed western lifestyle - one alien to the majority of the population in urban and rural areas who lived in poverty and destitution.

Of course, the abysmal failure of the Islamic Republic to live up to any of the slogans of the 1979 revolution has created a ready audience. The regime is widely hated, not only because of political repression, but runaway inflation, falling living standards and the harsh laws designed to ensure strict observance of Shia religious norms - an interference in the private lives of Iranians widely detested. Meanwhile, the gap between the rich and the poor is wider than before the revolution. It is therefore not surprising that some have illusions about the Pahlavi era and in particular Reza Shah (the ex-shah’s father) as a ‘moderniser’.

In many ways, given the number of memoirs and diaries of ministers and aides close to Mohammad Reza Shah, destroying any illusions about his character, it would not have been easy to present him as a hero of the nation. Notable among these books is the one written by former prime minister Asadollah Alam, The shah and I: the confidential diary of Iran’s Royal Court, 1969-1977. It vividly depicts a daily routine of misogynist debauchery and plotting against close relatives. According to The New York Times review, Alam shows the ex-shah as a megalomaniac, with a foul temper and contempt for almost everyone apart from himself.3

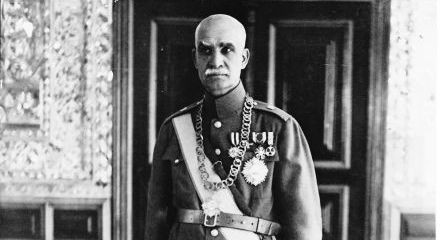

That is why it is easier to create a myth about Reza Khan (later Reza Shah), the mountebank founder of the Pahlavi dynasty, and give him credit for modernisation and progress. So who was Reza Khan? How did he come to power? What did he do during his rule? And why did the Allies dismiss him unceremoniously during World War II?

Coup of 1921

The fall of the Qajar dynasty (1789‑1925) was a result of political instability, foreign interference and internal corruption. By the early 20th century, the Qajars had lost much of their authority, with Iran suffering from economic decline and constant interventions by Russia and Britain. The dynasty officially ended in 1925, but its effective end came with the 1921 coup that brought Reza Khan to power.

Before talking about the coup of 1921, it is important to briefly summarise the plight of the Communist Party of Iran and its relations with Russia’s new Soviet Republic.

Based on research by Cosroe Chakeri4 and others, we know that during the early 20th century Iranian social democracy was divided into two factions. The left wing moved towards forming the CPI, while the right wing played a key role in establishing the Democratic Party of Iran. The DPI, which had some ties with Tehran’s only known trade union at the time (printing workers), quickly declined due to the constitutionalist revolution’s crisis and was dissolved by the 1921 pro-British coup, which also involved a certain Reza Khan.

Despite years of revolution and political upheaval, leftist groups failed to build strong grassroots organisations. Chakeri attributes this to their reliance on western organisational models, but another key issue was their belief that Iran needed a bourgeois revolution before socialist leadership could emerge. This theoretical position resurfaced soon after the CPI’s formation, following the declaration of the Soviet Socialist Republic of Iran in the Gilan province.

Internal debates within the CPI led to a split between the ‘national-revolutionary’ faction and what was referred to as the ‘pure communists’. The former supported alliances with landowners, if they were deemed useful against British imperialism, but this approach distanced them from real class struggles and left them vulnerable to co-option. They also opposed anti-landlord demonstrations, further alienating the poor. Meanwhile, the ‘pure communists’ advocated Iran’s ‘sovietisation’ by expelling the British and overthrowing the Qajar monarchy through a struggle against large landowners.

Soon after the October 1917 revolution, the Bolsheviks renounced tsarist-era arrangements with Britain, cancelled Iran’s debts, and made a commitment of non-intervention in Iranian affairs. However, in May 1920, the Red Navy landed in Gilan - officially to target White Russian forces, but also to support the establishment of the SSR of Iran in collaboration with Mirza Kuchik Khan’s Jangali movement. Despite ideological frictions, the SSRI played a crucial role in shaping Iran’s leftist landscape, contributing to the formation of both the CPI and the Socialist Party of Iran.

Chakeri highlights land redistribution as the central issue for the Soviet Republic in Gilan. Delays in addressing this led to a coup by the communists and leftwing Jangalis. While this may have been the only viable strategy to mobilise poor peasants and expand the revolution across Iran, internal divisions among the communists kept the situation unstable, ultimately causing the revolutionary coalition to collapse. Chakeri attributes much of the failure to harmful Russian interference, allegedly directed by Stalin. Regardless of who was most responsible, the Jangali movement was crushed in 1921, paving the way for Iran’s shift toward military dictatorship.

In many ways, early Soviet policy toward Iran reflected the broader contradictions within the Soviet state - caught between revolutionary ideals and the pragmatic need to secure the survival of the world’s first socialist regime. By 1921, leftist groups in Iran had been defeated and demoralised, leaving them with little political influence.5

The coup of 1921 was not aimed at the Qajar monarchy itself, but at the cabinet of Sepahbod Azam Fatḥ‑Allah-e Akbar and the oligarchy of landowners and bureaucratic officials dominating the regime. It was orchestrated by Sayyed Zia‑al‑Din Ṭabaṭabai and Colonel Reza Khan Mir Panj - later known as Reza Shah Pahlavi.

Sayyed Zia-al-Din - a young reformist journalist sympathetic to Alexander Kerensky’s ideals - enjoyed the trust of British military and diplomatic personnel in Tehran and maintained semi-official government ties. Meanwhile, Reza Khan, a Cossack officer of modest origins,6 had risen through military prowess and was chosen by Major General Edmund Ironside, head of Norper (North Persia) Force, to lead the reorganised Cossack unit near Qazvin under Lieutenant Colonel Henry Smyth. Also involved was Brigadier General Aḥmad Aqa (Amir-Aḥmadi), a senior Cossack officer who fought alongside Reza Khan in Gilan.

Britain’s role

During the Constitutional Revolution and World War I, provincial leaders and foreign powers had gained influence in Persia, while the Qajar state lacked the resources to assert sovereignty. The 1919 Anglo-Persian agreement aimed to strengthen the central government under British tutelage, but its implementation faced strong opposition, and Russian intervention in the north created instability. Many, including British officials, feared a Bolshevik-backed attack on Tehran after British troop withdrawal and sought preventive measures. Others hoped the pending Perso-Soviet treaty would mitigate the threat.

It was during this period of uncertainty that on February 18 1921 2,200 Cossacks and 100 gendarmes, led by Reza Khan, marched from Qazvin to Tehran, ignoring royal orders to return to barracks. Near Tehran, Reza Khan informed the cabinet, the shah and the British legation that the Cossacks aimed to install a strong government to pre-empt a Bolshevik assault. He pledged allegiance to the shah, but accused the ruling elite of ruining the country. The nearly bloodless capture of Tehran on February 21 sparked debate over whether the Tehran government, advised by the British legation, chose not to resist or if its soldiers refused to fight.

Post-coup, many political activists and oligarchs were arrested to prevent opposition and extract funds. Martial law was imposed: gatherings banned, the press suspended, government departments reorganised, and bars, gambling clubs, and theatres closed. Military governors replaced uncooperative provincial leaders. The shah appointed Zia-al-Din as prime minister with full powers and confirmed Reza Khan as Sardar-e Sepah (army commander). Zia-al-Din’s cabinet, although considered ‘honest’, was largely inexperienced.

Zia-al-Din’s reform programme prioritised a military build-up and included abrogating the Anglo-Russian Treaty and signing the Perso-Soviet treaty. While popular among reformers and common people, many observers, including foreigners, suspected British involvement in the coup and policy formulation. The coup was seen as an attempt to enforce the Anglo-Russian agreement’s spirit, with British financial and logistical support in Qazvin cited as crucial (Cossacks even boasted of British backing). Zia-al-Din sought British aid for reforms, but the foreign office was unresponsive. His failure to build a strong base led to his cabinet’s collapse within three months, leaving Reza Khan in full control.

Details of the coup’s planning remain unclear. Zia-al-Din and Reza Khan each later claimed sole credit, though both played key roles. Both were concerned about Persia’s fate and what they considered the “Bolshevik threat”. Zia-al-Din was busy drafting proposals to counter this “threat”.

Despite Zia-al-Din’s claims that the British were unaware of the coup, British military involvement is evident. Accounts denying their role lack any substantiation. British concerns over Bolshevik influence in Tehran and the military led Smyth to push for using troops based in Qazvin against opposition forces. The British minister in Tehran, Herman Norman, approved a plan to replace Tehran’s Cossacks with Reza Khan’s men from Qazvin. The shah and prime minister likely agreed, hoping to strengthen the government. Lieutenant-Colonels Smyth and WG Grey later admitted their involvement in the coup. Ironside, though not directly involved, had supported the coup led by Reza Khan.

The British Indian government encouraged the coup, aligning with its opposition to the 1919 Anglo-Persian agreement, which it saw as ‘harmful to regional interests’. Ardeshir-Ji Reporter, India’s chief adviser in Tehran, supported a strong government and had had ties to Reza Khan since 1917, claiming to have introduced him to Ironside.

In July 1921, nearly all remaining Red Army soldiers stationed in the northern Iranian province of Gilan crossed the Caspian Sea to return to Soviet territory. This retreat marked the definitive end of the Soviet Socialist Republic of Iran - a revolutionary enclave that collapsed due to ideological rifts between its Bolshevik and nationalist factions. The withdrawal also signalled the normalisation of Soviet-Iranian relations and, more abstractly, the decline of the fervour for global revolution and Soviet expansion southward.

In the following years, the Soviet People’s Commissariat of Foreign Affairs (NKID) not only fostered cooperation with Reza Khan’s government, but also turned against the nascent Iranian left, except when it aligned with Soviet interests against British influence, tribal forces or the clergy. This shift marked a new era of state-to-state relations, with the Soviets leveraging their partnership to secure economic agreements and counter British ambitions in Iranian oil.

Reza Shah’s rule

As for Reza Khan (later Reza Shah), he was very much a product of British imperialism, as were many of the policies he pursued during his reign:

-

Suppression of political freedom: Reza Shah’s regime was marked by authoritarianism, which stifled political dissent. Leftist movements, including socialist, communist and trade unionist organisations, faced systematic repression. His government dismantled worker-led movements and socialist groups, imprisoning or executing their leaders.

The suppression of independent trade unions denied workers the ability to negotiate better wages and conditions, enabling industrial elites and foreign investors, including the Anglo-Persian Oil Company (later British Petroleum) to superexploit Iranian labour.

-

Modernisation at the expense of the working class and peasantry: In essence, while modernisation was pursued, it came with severe political repression, particularly targeting socialist and communist ideologies, which were gaining popularity among industrial workers and students.

Reza Shah’s modernisation initiatives - such as legal and educational reforms, infrastructure development and industrial expansion - were primarily designed to strengthen the central state and military rather than improve the lives of ordinary Iranians.

- Agricultural reforms and the peasantry: Reza Shah sought to weaken large feudal landlords by nationalising some estates, but much of the land was redistributed to his political and military allies rather than poor peasants. Peasants, hoping for genuine land reform, remained dependent on landlords or were forced into urban slums as cheap factory labour.

-

Industrialisation without worker protection: While industrialisation was promoted, factory workers were denied the right to organise or demand better wages and conditions. Rapid urbanisation led to expanding slums, increased poverty and exploitation without any government support for workers.

His modernisation, hailed now as ‘progressive’, was elitist and exploitative, benefiting the ruling class, bureaucrats and military, while ignoring the needs of workers and peasants. Reza Shah’s approach subjugated the working masses under a new capitalist elite.

- Plundering Iran’s historical and cultural treasures: In 1931, Reza Shah permitted foreign archaeologists to excavate Persepolis, the ancient capital of the Achaemenid empire established by Darius the Great in the 6th century BCE. His government turned a blind eye, as these archaeologists removed countless priceless artefacts from the country.

-

Foreign economic dependence and oil concessions: A major critique of Reza Shah’s rule was his handling of Iran’s oil resources. Despite attempts to renegotiate oil concessions with the British, he failed to secure full control.

The Anglo-Persian Oil Company retained its grip over Iran’s oilfields, with revenues disproportionately benefiting the British government rather than the Iranian people. The British significantly boosted oil production, rising from approximately 5 million tons (equivalent to 37 million barrels) in 1932 to 10 million tons (over 74 million barrels) in 1938. However, only a small fraction of the revenue reached the treasury in Tehran, with oil revenues accounting for just 10% of the national budget.

- Lack of national economic independence: Reza Shah merely adjusted the terms of exploitation, leaving Iran’s economy dependent on foreign capital and resource extraction.

- Growing discontent: Many nationalist and leftwing activists viewed Reza Shah’s failure to nationalise oil as a betrayal of national sovereignty, perpetuating western exploitation. He confronted opposition from the tribes in Lorestan with brute force, with the army killing large numbers,

- Forced cultural and social reforms: While Reza Shah introduced western-style legal and educational reforms, his approach was coercive and dismissive of grassroots cultural change.

- Kashf-e Hijab (Mandatory unveiling of women): Though banning the veil was framed as progressive, leftist and feminist, critics view it as an authoritarian imposition rather than a women-led movement. Many working class and rural women, for whom veiling was a personal and traditional practice, saw this as forced westernisation rather than liberation. It also became a class issue, as middle class and upper class women used the term ‘chadori’ as an insult against women who continued wearing the chador (the traditional long hijab). As we know, the backlash came decades later, when the Islamic Republic took power.

- Education reforms favouring the elite: While secular education expanded, it primarily benefited urban elites, leaving rural populations and the children of workers and peasants with limited access, perpetuating social inequality.

- State-controlled secularism: The weakening of religious courts improved some legal aspects (eg, women’s rights). However, Reza Shah’s secularisation was authoritarian, aimed at centralising power rather than fostering a democratic society. Social progress requires grassroots mobilisation and worker empowerment, not top-down decrees by an autocratic ruler.

- Capitulation: Confronted with widespread anti-British protests and striving to project greater independence, he demanded that foreign advisors be directly employed by the government to ensure they were accountable to the local authorities rather than foreign powers. As part of his broader campaign to reduce foreign influence, he abolished the 19th-century capitulations granted to Europeans in 1928. These capitulations allowed Europeans to be tried under their consular courts instead of the Iranian legal system. He also transferred the authority to print money from the British Imperial Bank to the National Bank of Iran (Bank Melli Iran), shifted the administration of the telegraph system from the Indo-European Telegraph Company to the Iranian government, and ended the collection of customs by Belgian officials. He imposed restrictions on foreigners, barring them from running schools, owning land or travelling in the provinces without police authorisation (even though such authorisation was rarely denied).

Nazi Germany

Another key critique is Reza Shah’s growing ties with Nazi Germany in the 1930s. Leftist historians argue that his trade with Germany was driven by authoritarian and militaristic ambitions rather than a genuine pursuit of economic independence. However, there is no reason to believe he held actual fascist views.

But Reza Shah’s alignment with Nazi Germany made Iran vulnerable to Allied invasion during World War II, as they sought control of Iranian oil and supply routes. In August 1941, two Allied powers - Britain and the Soviet Union - launched a massive air, land and naval invasion of neutral Iran without a declaration of war. By late August, the Iranian military was in disarray, with the Allies controlling the skies and large portions of the country. Major cities like Tehran faced repeated air raids and, despite light casualties, Soviet leaflets warned of impending destruction, causing panic.

Food and water shortages worsened, and soldiers fled, fearing execution by Soviet forces. The royal family, except the shah and crown prince, fled to Isfahan, as the army Reza Shah had built collapsed. Many commanders acted incompetently or sympathised with the British, sabotaging resistance efforts. When Reza Shah discovered generals discussing surrender, he publicly humiliated and stripped the armed forces chief of his rank, threatening to execute him.

Reza Shah replaced pro-British prime minister Ali Mansur with Mohammad Ali Foroughi and ordered the military to cease resistance. Foroughi, resentful of the shah, negotiated with the Allies, implying Iran desired liberation from Reza Shah’s rule. The Allies demanded the expulsion of German nationals and the closure of their legations, but Reza Shah secretly helped Germans to escape. In response, the Red Army advanced on Tehran, prompting mass evacuations. Reza Shah abdicated on September 17 1941, and the Allies, unwilling to restore the Qajar dynasty, installed Crown Prince Mohammad Reza Pahlavi as the new shah.

The invasion had been driven by Reza Shah’s refusal to expel Germans and grant the Allies use of Iran’s railway, which was strategically vital for the war effort - Winston Churchill later called Iran the ‘Bridge of Victory’. Reza Shah had been forced to abdicate (marking the beginning of his son’s reign). His crackdown on socialist and communist groups, combined with his trade relations with fascist regimes, reflected reactionary, anti-left policies - very much appreciated by Nazi Germany.

Reza Shah’s reign was not about genuine ‘modernisation’, but a militarised capitalist project that prioritised state power, industrial elites and foreign interests, while systematically oppressing workers, peasants and political opponents. His reforms, though some were seemingly ‘progressive’, were exclusionary, failing to benefit the majority of Iran’s population.

-

See ‘Mek’s strange journey’ Weekly Worker July 6 2023: weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/1450/meks-strange-journey.↩︎

-

The New York Times April 26 1992: www.nytimes.com/1992/04/26/books/the-shah-was-in-a-foul-mood.html.↩︎

-

See, for example, C Chakeri The Soviet Socialist Republic of Iran, 1920-21 Pittsburgh PA 1995.↩︎

-

Ibid pp38-40.↩︎