16.01.2025

Baleful influence continues

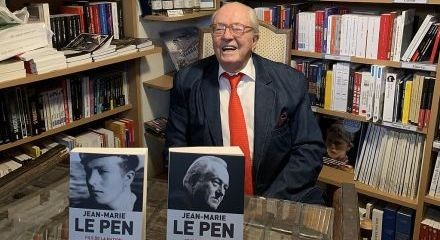

His death has been celebrated by the left. Paul Russell looks at the life, politics and family feuds of Jean-Marie Le Pen

Jean-Marie Le Pen’s death, aged 96, on January 7, had the French media buzzing with commentary, speculation and analysis, even though he had long retired from his lengthy political career. Born in Brittany in 1928, Le Pen studied at Paris law faculty and obtained his degree in 1948. He later completed an MA in political science, his thesis being ‘Anarchist tendencies in France since 1945’. Not yet a member of any political party, he gravitated to the rightwing Action Française, a nationalist and royalist organisation, founded in 1899.

During his military service Le Pen was posted to Indochina as a parachutist in 1953. He was there, in Vietnam, after the French defeat at Dien Bien Phu - a defeat which brought down the Paris government. On his return to France, he was elected to the national assembly - at 27 he was one of its youngest members, but soon rejoined his old military unit in Algeria, which was attempting to crush the National Liberation Front.

Legal battles

This military episode resulted in years of acrimony and legal battles between Le Pen and the French media over accusations that he had personally been responsible for torture during the interrogation of NLF suspects. At first he admitted his participation, justifying it on the grounds that it was the sole means of extracting information on the whereabouts of bombs set to explode in civilian areas. But later, with his political fortunes on the rise, he denied the accusations and sued various historians and newspapers. Invariably, Le Pen would lose in the high court or on appeal. In one of the more prominent trials, when he sued Le Monde, the daily newspaper dramatically presented as evidence a Hitler Youth dagger which carried his name. The dagger had been left, forgotten, in one of the torture chambers. Only in 2018, when his memoirs were published, did he finally admit to carrying out torture - “because it was necessary”.

Following Algerian independence, he re-entered politics and represented various small rightwing parties in the national assembly. Finally, in 1972 he co-founded the National Front with former Waffen-SS members Pierre Bousquet and Léon Gaultier, neo-Nazi sympathisers such as François Duprat and those nostalgic for French Algeria, such as Roger Holeindre, a member of the Organisation de l’Armée Secrète, which had plotted to topple president Charles de Gaulle in a military coup. From small beginnings, the party grew in popularity, focussing on immigration and ‘national renewal’. From 1983 until 2014, Le Pen was also elected to the European parliament, winning countless re-elections.

The National Front was first and foremost a nationalist party, claiming to be the true home of patriots. Its neoliberal policies of eliminating taxes and drastically reducing the size of the state, while severely curtailing the right to strike, were allied to an ultraconservative social programme to forbid homosexual marriage and abortion. From being an admirer of Ronald Reagan, after the fall of the Berlin Wall Le Pen turned against America and blamed an American Zionist plot to invade Iraq for the first Gulf War. In 1987, Le Pen called those affected by AIDS “lepers”, while at a public meeting in 2014 he told his audience that what he termed the “demographic problem” in Africa could be resolved in three months by Ebola.

In France, to deny the holocaust or other World War II crimes is against the law and on dozens of occasions Le Pen found himself condemned, fined and given suspended prison sentences. One such occasion occurred in 1969, when the text on the back cover of a record of Nazi songs entitled The Third Reich: voices and songs of the German revolution, published by Le Pen’s company, Serp, stated: “The rise to power of Adolf Hitler and the National Socialist Party was characterised by a powerful mass movement, ultimately popular and democratic, since it triumphed following regular electoral consultations, circumstances generally forgotten.”

In January 2005, Le Pen declared in the revisionist weekly Rivarol that “the German occupation was not particularly inhumane, even if there were blunders - inevitable in a country of 550,000 km2” - and that “if the Germans had multiplied mass executions in all corners, as the Vulgate affirms, there would have been no need for concentration camps for political deportees.” A final example shows the range of Le Pen’s racist vitriol: in an address given in Nice he stated: “You have a problem, it seems, with a few hundred Roma who have an itch-inducing and, let’s say, malodorous presence in the city.”

Over to Marine

The high watermark was reached in 2002, when Le Pen faced off Jacques Chirac in the second round of the presidential elections. The losing socialist candidate, Lionel Jospin, called on his followers to vote for Chirac in that second round - the first of many such instances of ‘tactical voting’ to defeat the National Front - and Le Pen was soundly beaten.

By 2012, he had renounced further attempts at the presidency and was succeeded by his daughter, Marine Le Pen, who changed the name of the party to Rassemblement bleu Marine, a title which lasted until 2017. She struggled to get candidates into the national assembly, though her niece, Marion Maréchal-Le Pen - granddaughter of Jean-Marie - was elected as the youngest ever member. Though Jean-Marie originally saw Marine as his successor, he began to sabotage her publicly declared aim of ‘detoxifying’ the party. Jean-Marie reaffirmed an earlier statement, made in a broadcast interview, that the gas chambers were merely a “historical detail”. Pressed by Marine and the party to accept that Marshal Pétain was a traitor to France, he refused.

Marine announced a disciplinary process against her father and called on him to retire from politics. Jean-Marie had been made honorary president of the National Front, but this post was rescinded. He cried foul and told the media that he hoped his daughter failed in her bid to become president. The party’s executive rescinded his membership - a measure passed by a majority, though Marion voted in his favour. He took legal action and, several court sessions later, was partially vindicated by having his honorary presidency restored, though Marine denied him access to executive meetings.

The first volume of Jean-Marie Le Pen’s memoirs was published by a small company in 2018, as the more established publishing houses withdrew from the bidding, under threats from some of their authors to leave them if they published more of his works. In his memoirs, he assesses his daughter Marine in this way: “She has certain qualities for politics: guts, drive, repartee. But she has no self-confidence. That explains her mistakes. Her dictatorial side … She cannot stand contradiction … I was the only opposition in her new FN: that is why she fired me.” He also criticised his daughter for the party’s “opening to the left” and its “desperate search for de-demonisation at a time when the devil is becoming popular”. In contrast, he described his granddaughter, Marion Maréchal, as an “exceptionally brilliant woman”.

Zemmour

In last summer’s general election, called suddenly by president Emmanuel Macron, Marion Maréchal formed an electoral pact with Eric Zemmour, a radio and television polemicist on the extreme right, who would stand against what was the National Front, now renamed National Rally. Eric Zemmour chose ‘Reconquest’ as the name of his new party, explaining that it was a reference to the Christian reconquest of the Iberian peninsula from the Muslims living there until the 15th century. Marion Maréchal, disdaining her aunt Marine, became a vocal Zemmour supporter. Le Monde published an article claiming that Zemmour and Jean-Marie Le Pen had lunch in January 2020 with Ursula Painvin, daughter of Joachim von Ribbentrop, the Third Reich’s minister of foreign affairs, hanged in 1946 after the Nuremberg trials. The newspaper noted that Ursula Painvin “encourages Éric Zemmour” with her “most admiring and friendly thoughts”. But, as is the case with such neo-fascist alliances, after Zemmour and his party were comprehensively trounced at the elections, with not a single successful candidate, Marion Maréchal publicly broke with Zemmour and has since made reconciliatory gestures to her aunt.

Jean-Marie Le Pen’s death was celebrated across French cities by leftwing activists and militants, to the point that the rightwing current affairs weekly, Le Point, wrote: “These disgraceful celebrations are an echo of the [French Revolutionary] Terror.” Even in death, there is no doubt that his baleful influence continues across the political right.