03.10.2024

Desire utopia but neglect politics

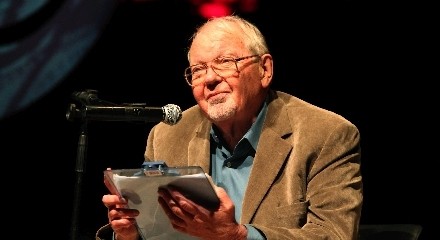

Mike Belbin remembers Fredric Jameson, April 14 1934-September 22 2024

We are quite used to Marxist literary critics telling us about the historical context of Jane Austen or TS Eliot. One critic, Fredric Jameson, who died last month, however, could show you a stylistic-historical account of such knotty creations as structuralism and postmodernism - as well as Star wars and a new hotel foyer.

Jameson’s most lauded works were Postmodernism: or the cultural logic of late capitalism (1991) and The political unconscious: narrative as a socially symbolic act (1981). He began though in 1961 by publishing his dissertation, Sartre: the origins of a style.

Born in Cleveland Ohio in 1934 and the son of a medical doctor, he travelled after graduation to Europe - to Aix-en-Provence, Munich and Berlin. It was there that he extended his knowledge of post-war thinkers like the German Frankfurt School and the French structuralists. Back in the US he taught at Harvard and in California alongside Herbert Marcuse. In 1969 he co-founded the Marxist Literary Group with a number of graduate students.

He continued writing about European thinkers from Adorno to Althusser - not only repeating their concepts, but locating them in conversations about social structure and cultural products. On this he wrote dense but suggestive critiques like Marxism and form (1971) and The prison-house of language:a critical account of structuralism and Russian formalism (1972). He was both learning from the recent turn to language and semiotics, and situating them in the period of late ‘cultural’ capitalism.

In 1991 Jameson produced Postmodernism - a bestselling work on the contemporary theories of the (current) era called postmodernism. In the 1990s the book was especially influential in China. In his more recent work, Jameson continued his interest in utopias and science fiction, as well as reviewing east Asian thrillers and discussing in detail Hegel and Marx’s Capital before completing his last acclaimed work, Inventions of a present: the novel in its crisis of globalisation.

In The political unconscious, Jameson covers cultural products like Sir Gawain and the green knight and modernists like the ‘adventure’ writer, Joseph Conrad - proposing the broadest level of interpretation in which to understand them. He situates these (even tribal pottery) in the succession of modes of production. Art works are each a symbolic action in a situation of a particular class tension. They can be read both by a negative hermeneutic (revealing class tensions), but also a positive one (utopian). They contain the history that hurts us, as well as settling us for our position in an unfair world.

My example is Jane Austen’s novel, Pride and prejudice, which shows a world where a middle class family like the Bennets can be down at heel and insulted by an aristocrat like Darcy. The book figures as a warning to the regency, when republicanism threatened the UK’s cohesion, by resolving this fraught situaton in an ending where one of the daughters, Elizabeth, marries mansion-owning Darcy - but only after much struggle as to who is worthwhile. Austen attacks ‘pride’ - through overcoming the ‘prejudice’ of the rising middle class. A social peace is achieved and a unity - or, if you like, a wedding - of classes celebrated.

In his discussion of the 1975 film, Dog day afternoon, Jameson revealed a story which ends not with social peace, but with a more anxious reflection on crime and justice. In this narrative two lower-middle class men rob a bank (one, Sonny, is played by Al Pacino), where their escape is prevented not just by a TV news show wanting an interview, but the New York police putting them under public siege. The FBI, which Jameson identifies as figures of corporate power, sideline the more empathetic local police and negotiate the robbers into an ambush.

At one point before this there are stirrings of solidarity between the bank employees taken hostage (mainly female) and the robbers, while Sonny gets to inspire the ghetto crowds behind the police lines by starting a chant of “Attica, Attica” - a reference to a prison massacre some years before. However, all this collective activity disappears and one of the robbers is shot in the ambush. Sonny is left alone uneasy at what has occurred: he is no longer a deferential member of the middle class, but is cut adrift.

Causality

Jameson situates art at a specific level of the social structure, where society’s injustices are both admitted (realism) and symbolically overcome. In doing this he draws on Althusser’s concept of ‘structural causality’. Art serves the system, but not in some direct propaganda way. This is contrasted with the more Hegelian-Marxist concept of ‘expressive causality’, where all levels are directly made in the image of the mode of production. That is, more like a choir, where the function of the whole is to promote one theme in unison. The choir sings one song, with small differences in voice - tenor, baritone, soprano - whereas Althusser’s differentiated structure is more like an orchestra playing a symphony, where different tones and instruments contribute to the whole.In their own way and at different times and sections.

Parliamentary politics, after all, is not the same as the law. Jameson points out that not all levels or voices say the same thing: they exhibit differences, but are still ‘united’, as it were, by an operation in favour of the mode of production. Let us take a text like Sir Gawain and the green knight. This magic knight that faces King Arthur’s court is not a portrait of an actual feudal landowner, but a symbol of a felt contradiction - a figure of antagonism within the class. Gawain steps forward for combat, although it is not a dragon he faces, but another knight. However, he is shown doing it without abandoning the class’s code of chivalry, as in his courteous refusal of sexual offers from the green knight’s lady. We can feel for his plight, but admire him doing the right thing, even at the risk of his life. Life is tough, but the hero overcomes it in the right way.

In the 1980s, Jameson turned his attention to the present in his bestselling Postmodernism. Rather than treat the trendy concept of postmodernity as a distraction from the processes of globalisation (ideology as mask) he examines the cultural style of the period and what this tells us about the political conjuncture.

In fact Jameson begins from the very definition of the postmodern given by theorist Jean-François Lyotard. Famously, Lyotard names the key to postmodernism as the suspicion of grand narratives; the lack of people’s trust now in the future as something different from the past; no more hope in progress, whether liberal or socialist.

Jameson begins from this idea to describe our period’s cultural aspects, which he characterises as marked by styles of ‘pastiche’ - parody without satire - giving examples from film, TV and architecture. While modernism from the 1920s quoted from different cultures (Aztec, African, ancient Egypt, the dramatic monologues of Shakespeare), postmodern works cannibalise such elements, but erase any sense of critical or historical distance. As he puts it, “there no longer seems to be any organic relationship between the history we learn from schoolbooks and the lived experience of the current, multinational, high-rise, stagflated city of the newspapers and of our own everyday life”.

While finance capital operates without most of us understanding it, the promises of actually existing communism and the radical 1960s have become dust (or caricatures), while the majority enjoy ‘stylish’ 1930s and 40s TV, from Agatha Christie to Batman spin-offs. Since Warhol, high art has become branding, reaching ever higher prices. The 1980s did indeed seem a dead end - full of nostalgia and the death of historical change. As Jameson remarked, the mega-movie franchise, Star wars, was not about the future, but nostalgic, made to satisfy longings of baby boomers and younger consumers for earlier sci‑fi serials of adventure and youthful astro warriors. Sequels and fantasy (Lord of the rings, Harry Potter) deny the present (even as analogy) in ‘simple, pure entertainment’.

It is debatable whether any counterforces have arisen lately which challenge this with a sense that we can have a change and shape a different future. It is debatable too whether Jameson’s series of evocative descriptions have aided this process. Fellow Marxist Terry Eagleton took up this question in several essays on Jameson’s method and politics.1

Eagleton admires Jameson’s account of so many different methods and ideas, both using them and marking their limitation as one-sided approaches to the totality. But he notes that this may only amount to a too liberal adoption - ie, without their contradictions - can we mix Althusser with Derrida? He also mentions Jameson’s neglect of politics, with no discussion at all of the likes of Lenin, Luxemburg or the problems of revolutionary strategy. Eagleton remarks that therefore Jameson’s work too is constrained by its historical context. “It is no accident,” he says, “that the declared political correlative of his theoretical pluralism is the amorphousness of ‘alliance’ politics” (p63). He remarks:

Jameson’s style displays an intriguing ambivalence of commentary and critique; that this springs from a similarly ambivalent relation to bourgeois culture, at once over-appropriative and over-generous; and that all this in turn may be illuminated by the essentially Hegelian cast of Jameson’s Marxism, which tends to subordinate political conflict to theoretical Aufhebung [ie, synthesis] (p76).

Jameson does have an answer to this: his model of the differentiated levels of the social formation contains survivals from previous modes of production, integrated into the current dominant mode and lately ready to be opposed as ‘out of date’ with contemporary capitalism by reforming liberals and radicals: “We are not going back,” declares Kamala Harris, but she does not mean there will be deep change.

Jameson has otherwise argued:

The affirmation of radical feminism, therefore, that to annul the patriarchal is the most radical act - insofar as it includes and subsumes more partial demands, such as liberation from the commodity form - is thus perfectly consistent with an expanded Marxian framework, for which the transformation of our own dominant mode of production must be accompanied and completed by an equally radical reconstruction of all the more archaic modes of production with which it structurally coexists.2

Future

Let us all unite then - all the sections, methods, hopes - but with democratic centralism, of course: that is, with no lack of mutual criticism, though in a common project against the totality.

One recent film shows something like this: the latest Alien sequel, Alien: Romulus, where a mixed group have to struggle, without arrogance, with their personal difficulties, as well as against the latest progeny of the Alien franchise - a monster that turns out to be still threatening, but this time part-human.

But if culture (from speeches and editorials to TV drama and best-selling novels) is an operation to stir, then satisfy, the project of exposure is still useful as part of a project for change - not only in opposition to closure (endings happy or hopeless) but acknowledging that these products, in their appeal to us humans, reveal that the utopian is still desired and a politics of a different future is still possible.