26.09.2024

Fetishising revolutionary crisis

Clinging to the general strike, and to the idea of taking the tide at the flood, is at the core of present failures. Mike Macnair argues that Steve Bloom’s call for ‘synthesis’ is badly misconceived

This article begins a response to Steve Bloom’s recent series criticising my book, Revolutionary strategy.1 In summary, although comrade Bloom’s first article claims to be seeking a synthesis, he is not actually proposing a synthesis, but a capitulation on my part.

I would be capitulating to what appears, from his three articles taken together, to be an ‘offer’ of a form of Trotskyism that abandons the decisions on forms of party organisation made by the Russian communists and Comintern in the face of civil war in 1918-21, without abandoning any of the other, connected, judgments made by the Russian communists and Comintern in 1918-23; but which conversely refuses to accept responsibility for the repeated failures of real existent Trotskyismus since 1945.

In support of this proposal comrade Bloom relies on fundamental errors of method. First, he deploys ‘physics envy’ arguments (we cannot attain the degree of probability in our political or historical judgments that can be attained by 20th century experimental methods in physics and related disciplines) to deny the utility of hindsight in politics or the testability of political/historical claims.

Second, his response to my use of history entails arbitrary caesuras that cut off periods from one another, thereby prohibiting historical causality between them. Thus he refuses my arguments for the relevance of the weaknesses of the pre-1914 left (the Bakuninists, the syndicalists, the ‘mass-strikist’ wings within the Second International) to understanding the present problem. And he draws a sharp line in the mid-1920s, so that the decisions of the Bolsheviks and Comintern in 1918-21 have no causal relation to what followed.

He similarly draws a sharp line between the 1970s and 1989, so that the transparent political dynamics of the fall of the eastern bloc regimes in 1989-91 and after cannot be used to understand the very similar political dynamics of Hungary in 1956 before the second Soviet intervention, of Czechoslovakia in 1968, and of Poland in 1980-82. I flag here the fact that the Mandelite Fourth International radically failed to understand 1989 and after, which should by now be completely obvious. Its failure of understanding of the dynamics of 1989 and after was precisely because its misconceptions about 1956, 1968 and 1980-82 as examples of potential ‘political revolution’ led it to have radically unrealistic judgments about Gorbachev, Yeltsin and co.

At Communist University in August 2023 we offered comrade Gerry Downing, who holds ‘orthodox Trotskyist’ views, and his co-thinkers in Socialist Fight, membership of the CPGB with factional rights, including the right of publication. After a little hesitation comrade Downing refused: he wants to build an organisation based on Trotskyist theory (he said at the August meeting that the CPGB would not be welcome to join Socialist Fight with the rights of a public faction: we are not Trotskyists). We could make this offer because in our view party organisation is not based on agreement to any sort of theory, but on acceptance as the basis of common work of a short, stated political programme (which is available both in print and online).

The issue is not directly posed to comrade Bloom: he is in the USA, not the UK, and the Marxist Unity Group is not an alter ego of the CPGB. But, even if he was seeking ‘synthesis’, rather than merely asserting the continued validity of (his version of) Trotskyism, seeking that as the basis for unity poses the issue in the same way as comrade Downing: that is, as unity based on theoretical agreement.

Synthesis

I begin with comrade Bloom’s claim in his first article to be offering a ‘synthesis’ of his own views and mine. From a Marxist, one would normally expect this to be a ‘dialectical’ reference (JG Fichte’s tag thesis-antithesis-synthesis - commonly, though inaccurately, used to characterise GWF Hegel’s dialectic2).

One might then imagine that the idea of the general strike and the Grand National Trades Union that went along with it (thesis) was negated/aufgehoben in the antithesis, Chartism, which aimed for a mass political movement round the six points of the Charter; that the ideas of Chartism persist in Marx’s arguments for working class political action against the Proudhonists and Bakuninists in 1869-72; and that the synthesis, the negation of the negation and Aufhebung of the Marxists’ negation of the general strike in the political movement, is then the (failed) Belgian general strike of 1902 for extended suffrage, the Russian revolutionary crisis of 1905, Rosa Luxemburg’s arguments in The mass strike (1906) and her arguments for the mass strike for suffrage in the Prussian suffrage campaign in The next step (1910). Here the strike movement serves the political movement, because it seeks constitutional change.

The defect of such an approach would, plainly enough, be that the dialectical movement of history ends in Luxemburg’s ‘synthesis’: Luxemburg no more identified the end of the history of the proletarian strategy in 1910 than Francis Fukuyama identified the end of history in general in 1989.

But what comrade Bloom offers is not such a dialectical movement. Rather, what he proposes is at most ‘synthesis’ in the sense of pasting together his own views with a part of mine. In the summary of my argument at the end of Revolutionary strategy (pp161-67), he proposes to set on one side my first and most fundamental point - the class perspective, as opposed to the various forms of people’s frontism - on the basis that we disagree on the issue.

He also sets on one side point 7, which asserts the legitimacy of illegal strikes and other forms of direct action to defend workers’ immediate interests, given the corrupt character of the ‘democratic’ (rule-of-law liberal) regime, while rejecting the idea that the use of force or minority action can be a strategy. This second point he claims is “useful clarifications … but not really a point of strategy in itself”. This would be true if you accept comrade Bloom’s arguments for the mass strike strategy, but false if you do not: as soon as you assert, as I do, that it would not be acceptable, or indeed possible, “to impose our minimum programme on the society as a whole through minority action”, the issue is posed as a point of strategy.

He accepts point 2 on the meaning of the working class: which is only really relevant if you accept point 1, which he does not. Similarly, he accepts point 3 on the working class collectively appropriating the means of production through democratic-republican decision-making: which, again, depends on the argument for the class perspective in point 1, since strategic (as opposed to tactical) alliances with sections of the property-possessing middle classes, however ‘oppressed’ they may be, are inconsistent with this perspective.

He says that “Points 4, 5 and 6 reflect the problem with Mike’s misunderstanding/rejection of the mass strike and can, therefore, be fairly easily adjusted if we are able to accept the synthesis proposal I make above.” That is, he finds potentially acceptable only if they were ‘synthesised’ with the mass strike strategy, para 4 (the working class needs to fight for political power), point 5 (self-government of the localities and sectors, not Bonapartist centralism or constitutional federalism), and point 6 (achieving the democratic republic requires clear majority support for the democratic republic, not the action of an enlightened minority).

He agrees also with point 8 (political party standing for the independent interests of the working class, which again depends on point 1, on the class perspective) and point 9, that the party needs to be democratic-republican in its forms. He agrees with point 10 (the party needs to be independent both of the capitalists and their state, and cannot take responsibility as a minority in government without immediate commitment to bring in the democratic republic); and with point 11: that, though a unified workers’ party including both the loyalist left and communists is desirable, it is impossible, because the loyalists insist on censoring the communists as a condition for unity; so that united front policies are necessary.

That said, in a footnote he argues that “on the party-building question we also need a synthesis, since elements of what traditionalists might tell us about the need for a ‘vanguard party’ continue to be correct, even if their overall approach demonstrably leads to the creation of sects rather than revolutionary parties”. Since I argue about this issue more elaborately on pp91-98 of the book,3 this observation is insufficient to make clear what “elements of what traditionalists might tell us” comrade Bloom wishes to defend that I do not already defend.

He disagrees with point 12, essentially on the basis of the supposed ‘law of uneven development’.4 This is a very fundamental strategic issue, and really central to the current implausibility of left alternatives to ‘capitalist realism’. However, he accepts point 13, that there cannot be working class class-political consciousness in a single country, so that an international is essential; and point 14, that, as at the national level, so at the international level, it is essential to reject “both bureaucratic/Bonapartist centralism and legal federalism”. Again, however, the question is posed: how far the caveat in his footnote, that a “synthesis” is needed on the party question with “elements of what traditionalists might tell us”, is consistent with his real acceptance of these points.

I have listed all this at length in order to demonstrate just how little comrade Bloom concedes to my arguments. In essence, he agrees only to those elements in my arguments that are consistent with views he already holds; or, put another way, with the general views of the Mandelite Fourth International before its most recent evolution. At the core, I am asked to abandon the critique of general-strikism on the ground that I ‘misunderstand’ it or that I ‘misunderstand’ what counts as strategy. In comrade Bloom’s second and third articles, we will find (as I indicated above) that he claims that I am also wrong on pretty much all the rest of my historical judgments, in so far as these depart from Trotskyism.

It is for this reason that I say that what comrade Bloom seeks is not synthesis, but political capitulation. Further, by way of the ‘synthesis’ argument, his proposal (if I accepted it) would suppress the existence of serious political differences about present political tasks, by blurring these differences in the direction of agnosticism.

As far as comrade Bloom’s relation to the Marxist Unity Group is concerned (and it is, of course, up to them to take their own decisions), if they accepted comrade Bloom’s ‘synthesis’ as a basis for unity, this would not amount to an open factional participation of Trotskyists on the basis of an acceptance of a common programme as the basis for common action (as we in CPGB proposed to comrade Downing in 2023), while continuing fighting on the differences. It would amount, rather, to a typical Mandelite entry-tactic operation, in which differences are blurred in the hope of ‘capturing’ the target group as a ‘transitional organisation’ on the imagined, but usually illusory, road to a larger Mandelite group.

Strategy

The series that became Revolutionary strategy was written in 2006 and the book was published in 2008. As is transparent from the first chapter, it does not start from the history of the workers’ movement, negative balance-sheets, and so on. It starts from the situation of the left in the present (meaning, our inferences that the, usually recent, past will continue into the, usually near, future, which is what ‘the present’ generally means). This question comrade Bloom does not address at all.

I judged in 2006-08 that the global situation was characterised by (1) the deepening weakness of capitalism, and the end of the liberal triumphalism of the 1990s; but (2) that that the principal gainers from this development are forms of the nationalist-patriarchalist and religious right. It seems to me obvious that these judgments are confirmed by the subsequent evolution of politics. As far as the left is concerned, I judged in 2006-08 that it remains in the shadow of the Soviet-style bureaucratic regimes, and that this shadow is reflected in division between, on the one hand, a broad left committed to nationalism, people’s front politics and bureaucratism, following old ‘official communist’ politics even when they are by origin social democrats, and a far left that “is widely - and often accurately - perceived as undemocratic in its internal functioning, as tending to export this undemocratic practice into the broader movement, and as unable to unite its own forces for effective action” (pp9-10).

Again, it seems to me clear that this problem has if anything worsened since 2008. The 2019 collapse of the US International Socialist Organisation, which had deliberately attempted to distance itself from the bureaucratic centralism of its ‘mothership’, the British Socialist Workers’ Party, but without breaking with the SWP’s fundamental conceptions of what a party is for, is exemplary; there are many other examples.

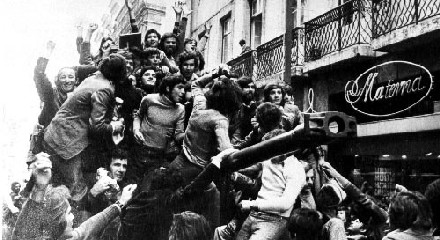

Nor is this a short-term problem. It is now 35 years since the fall of the Soviet bloc, which many leftists imagined would clear the way for their own progress. It did not. It is more than 60 years since the ‘new left’ ‘rediscovered’ Rosa Luxemburg as a ‘western Marxist’, and since Hal Draper’s 1960 article, ‘The two souls of socialism’, that coined the idea of ‘socialism from below’. This 60-plus years is a history of consistent failures of far-left groups to be able to give effective political leadership during real revolutionary crises (as in Chile under Popular Unity; Argentina in the same period; Portugal in 1974-76; Iran in 1979-80; and others) and large mass movements (as in France in 1968; the Italian ‘creeping May’; the British strike movement of 1970-74; and many others).

They have equally been unable to turn the mass movement into a means of reaching mass scale: unlike, for example, the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party factions in 1905, or the Chinese Communist Party in 1925-27. Equally, far-left groups have been unable to grow beyond a few thousand outside such conditions - unlike, in their earlier histories, socialist and communist parties.5

After this 60-year history of failure, continuing to repeat the nostrums created by 1960s ‘new left’ re-readings of Lenin, Luxemburg and Trotsky is like keeping banging your head against a brick wall in the hope that finally you will knock the wall down.6 The problem is not the mere fact of repeated defeats, but repeated and increasing ineffectiveness, splintering and marginality.

Revolutionary strategy is about what to do now about this situation. It is for this reason that I insist that ‘strategy’ is about the long-term coordinates of political action. It is for this reason that I reject out of hand comrade Bloom’s argument that “when the word ‘strategy’ is used by proponents of the mass strike, they are not using it in the same way that Mike is in the title of his book”. The point is precisely that, as I argue on pp168-69 of the book,

The trouble is that social revolution and political revolution alike involve both the gradual molecular processes of change and the short burst of crisis. By fetishising the short burst of crisis, the Trotskyists devalue the slow, patient work of building up a political party on the basis of a minimum political programme in times of molecular processes of change. The result is, when crisis does break out, they have created only sects, not a party, and are effectively powerless.7

Party

The issue is, precisely, what the point of a workers’ party is, and hence what sort of party we should be seeking to create now. In this context, comrade Bloom wants to overcome the problems of the bureaucratic-centralist sects (though how far remains unclear, given the caveat in his footnote, mentioned above). But he clings to the conception of the purpose and tasks of the party that actually necessarily entail the bureaucratic-centralist sect. As I have argued elsewhere, advocates of ‘socialism from below’ seem to be particularly prone to fall into bureaucratic-centralism; for this reason.8

The core of the issue is precisely the “tide in the affairs of men” issue - of the need for action at a particular moment in time - which comrade Bloom starts with, and which he makes the centrepiece of his argument. Begin with comrade Bloom’s comment on the question of the timing of the October revolution:

This was the danger Lenin noted in 1917, when he objected to Trotsky’s plan to wait until the Congress of Soviets to give the Bolsheviks a clear democratic mandate for the insurrection. Lenin feared that even a delay of weeks might result in an ebb in the mass sentiment for revolution, making insurrection more difficult or even impossible. Lenin’s fears turned out to be unfounded. But they were based on a proper understanding of how revolutionary situations unfold - in particular how they come upon us and then disappear in a matter of weeks or months, if we fail to take advantage, in a timely way, of the majority sentiment in favour of revolution that has developed, while some tangible form of mass mobilisation is ascendant.

This is personalised as ‘Lenin versus Trotsky’.9 It is actually Lenin versus the Bolshevik leadership majority (which sided with Trotsky on the issue). Here, the leadership majority were clearly correct: October could not have succeeded without the alliance between the Bolsheviks, probably representing a majority of the urban proletariat (which was, however, a small minority of the country), and the Left Socialist Revolutionaries, probably representing a majority of the peasantry (which was the large majority class). That alliance was possible because the Petrograd Military-Revolutionary Committee, which overthrew the provisional government, acted in the name of the Congress of Soviets that was about to meet. A ‘Bolshevik-only’ insurrectionary general strike without that political alliance and its constitutional legitimacy would have met the fate of the Berlin radicals’ attempted forcible resistance of January 1919, or the 1921 ‘March Action’: that is, decisive and demoralising defeat. It is the democratic political commitments of the Bolsheviks, and their commitment to the worker-peasant alliance, which allowed the Bolshevik leadership to reach the right decision here.

We can, in fact, go further. Luxemburg argued in The mass strike that

To give the cue for, and the direction to, the fight; to so regulate the tactics of the political struggle in its every phase and at its every moment that the entire sum of the available power of the proletariat, which is already released and active, will find expression in the battle array of the party; to see that the tactics of the social democrats are decided according to their resoluteness and acuteness and that they never fall below the level demanded by the actual relations of forces, but rather rise above it - that is the most important task of the directing body in a period of mass strikes. And this direction changes of itself, to a certain extent, into technical direction. A consistent, resolute, progressive tactic on the part of the social democrats produces in the masses a feeling of security, self-confidence and desire for struggle; a vacillating weak tactic, based on an underestimation of the proletariat, has a crippling and confusing effect upon the masses.10

And in ‘The next step’ (1910) we find:

For the expressions of the masses’ will in the political struggle cannot be held at one and the same level artificially or for any length of time, nor can they be encapsulated in one and the same form. They must be intensified, concentrated and must take on new and more effective forms. Once unleashed, the mass action must go forward. And if at the acknowledged moment the leading party lacks the resolve to provide the masses with the necessary watchwords, then they are inevitably overcome by a certain disillusionment, their courage vanishes and the action collapses of itself.11

A German left that had been trained up with arguments like these (and those of Anton Pannekoek - for example, in his 1912 ‘Marxist theory and revolutionary tactics’, part of the same debate12), would inevitably be unable to hold radicalised local mass movements back from minority adventurism in order to allow the ‘rearguard’ to catch up, as the Bolsheviks did in the ‘July Days’ in 1917. And so it proved in 1919 and 1921 …

Initiative

The significance of timing is not unique to conditions of revolutionary crisis. On the one hand, if George Galloway had walked out of the Labour Party and called for a new party on the day British troops went into Iraq on March 20 2003, as opposed to hanging on until the Labour Party expelled him on October 23, it is likely that the resulting movement would have been more powerful than Respect (founded January 2004). On the other hand, the role of the SWP in Respect was possible because of its role in Stop the War Coalition. And its role in StWC was possible because the SWP seized the initiative in creating the coalition in 2001 to campaign against the war on Afghanistan.

This ‘seizing the initiative’ is precisely the problem. In the first place, each grouplet is determined to have the initiative, and hence creates its own front, which it hopes will be the one that ‘takes off’ (as StWC ‘took off’). Equally, groups walk out if they lose the majority (and thus initiative control) - thus the Socialist Party in England and Wales in the Socialist Alliance in 2001, and thus the SWP in Respect in 2007. Or they create competing initiatives to prevent their rivals’ operations ‘taking off’ (as the three main French far-left groups have done against each other, repeatedly since the 1970s).

In terms of internal organisation, the centrality of creating a party that can seize the moment implies that internal dissent is as such antagonistic to the role of the party. The International Left Opposition pre-conference in February 1933 correctly resolved that

The frequent practical objections, based on the ‘loss of time’ in abiding by democratic methods, mount to short-sighted opportunism. The education and consolidation of the organisation is a most important task. Neither time nor effort should be spared for its fulfilment. Moreover, party democracy, as the only conceivable guarantee against unprincipled conflicts and unmotivated splits, in the last analysis does not increase the overhead costs of development, but reduces them.13

The problem is that, if the task of the party is to catch the moment, to take the tide at the flood, to be “a political party that is capable of taking power, precisely at that moment when the mass strike poses this as a social necessity”, this point resolved by the ILO cannot be true: the loss of time “wasted talking to ourselves”, as advocates of bureaucratic centralism of various sorts put it, is fatal to the party. Hence, in reality, the driver for the endless splittism of the far left: comrades are reluctant to “waste time talking to ourselves” and hence either minorities walk out of organisations in search of fresh fields and pastures new, or majorities find factitious excuses of one sort or another to drive minorities out. The advocates of the mass strike policy before 1914 were already driven towards bureaucratic-centralist sect-making in Luxemburg’s and Leo Jogiches’ Social Democracy of the Kingdom of Poland and Lithuania, and in the US and British De Leonist Socialist Labour Parties. The reason being that the mass strike policy logically implied party control over the trade unions, and logically implied that internal dissent is time-wasting.

Back to Bolshevism and October. Their strategic orientation to political democracy, and the worker-peasant alliance, enabled the Bolsheviks to grow into a large-minority party with a mass-circulation paper in 1912; enabled the Bolsheviks to pursue a policy of patient explanation with a view to winning the majority during 1917; and enabled them to make the practical alliance with the Left SRs that actually took power.

In reality, all this was the inheritance of August Bebel’s and Wilhelm Liebknecht’s strategic conception, which was the foundation of the revolutionary social democracy of pre-1914. And this in turn was the legacy of Marx’s and Engels’ arguments against the Bakuninists, for a workers’ party that attempted not to lead the strike movement, but to create a political voice for the class in high politics.

So ‘synthesising’ does not work. This is not an issue just about what would be done under conditions of revolutionary crisis. It is an issue about what should be done under present conditions. Fetishising revolutionary crisis and clinging to the general strike and to the idea of taking the tide at the flood is at the core of the present failures of the far left.

-

‘In search of a synthesis’ Weekly Worker August 1 2024 (weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/1502/in-search-of-a-synthesis); ‘Historical and methodological differences’, August 29 (weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/1504/historical-and-methodological-differences); ‘Matters past and present’. September 12 (weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/1506/matters-past-and-present).↩︎

-

GE Mueller, ‘The Hegel legend of “thesis-antithesis-synthesis”’ Journal of the History of Ideas Vol 19 (1958), pp411-14. JE Maybee, ‘Hegel’s dialectics’ (plato.stanford.edu/entries/hegel-dialectics) (2020) discusses in more depth the limited basis for the use of Fichte’s tag to characterise Hegel’s logic.↩︎

-

And I have argued about it at considerably more length elsewhere. See, for example, ‘Origins of democratic centralism’ Weekly Worker November 5 2015 (weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/1081/origins-of-democratic-centralism) introducing Ben Lewis’s translation of Karl Kautsky’s ‘Constituency and Party’; ‘Full-timers and “cadre”’ April 25 2019 (weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/1248/full-timers-and-cadre), ‘Reclaiming democratic centralism’ May 23 2019 (weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/1252/reclaiming-democratic-centralism); ‘Negations of democratic centralism’ May 30 2019 (weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/1253/negations-of-democratic-centralism), on the collapse of the US ISO; and my 2020 five-part series critiquing Neil Faulkner and Martin Thomas on the issue, linked at communistuniversity.uk/mike-macnair-programme-and-party-articles. Cf also Ben Lewis, ‘Sources, streams and confluence’ Weekly Worker August 25 2016 (weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/1119/sources-streams-and-confluence); Lars T Lih, ‘Fortunes of a formula’ (johnriddell.com/2013/04/14/fortunes-of-a-formula-from-democratic-centralism-to-democratic-centralism), and ‘Democratic centralism: further fortunes of a formula’ Weekly Worker July 25 2013 (weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/972/democratic-centralism-further-fortunes-of-a-formul).↩︎

-

It does not assist to modify this supposed ‘law’ by speaking of a law of uneven and combined development. I polemicised against this in 2008: ‘Stalinist illusions exposed’ Weekly Worker September 17 2008 (weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/737/stalinist-illusions-exposed).↩︎

-

I put on one side the ephemeral large sizes of Lotta Continua in 1969-76 or of the Iranian Fedayeen in the revolution of 1979, since in both cases the groups continued to think like, and organise like, groups of a few thousand - and hence could not survive political differences.↩︎

-

See also my ‘Defeat was fault of enemy machine guns’ Weekly Worker May 24 2007 (weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/674/defeat-was-fault-of-enemy-machine-guns).↩︎

-

I make the same point in my 2019 series on the US Kautsky debate: ‘Widening frame of debate’, August 8 (weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/1263/widening-frame-of-debate), ‘Fabian or anarchist?’. August 16 (weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/1264/fabian-or-anarchist), ‘Organisation or “direct actionism”?’, September 5 (weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/1265/organisation-or-direct-actionism), ‘Containing our movement in “safe” forms’, September 12 (weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/1266/containing-our-movement-in-safe-forms), ‘Revolution and reforms’ September 20 (weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/1267/revolution-and-reforms), especially in the last three articles.↩︎

-

I argue this most elaborately in ‘Socialism from below: a delusion’ Weekly Worker August 13 2015 (weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/1071/socialism-from-below-a-delusion).↩︎

-

Part of the cult-of-personality stuff developed from 1924; see LT Lih, ‘100 years is enough’ Weekly Worker supplement, September 19 2024 (weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/1507/a-hundred-years-is-enough).↩︎

-

www.marxists.org/archive/luxemburg/1906/mass-strike/ch04.htm.↩︎

-

W Reisner (ed) Documents of the Fourth International New York 1973, p29.↩︎