23.05.2024

Your next president will be

Winning in June depends on who the supreme leader favours. Yassamine Mather also says that being elected president can amount to a poisoned chalice

Following the helicopter crash on May 19 in which he was killed, ayatollah Ebrahim Raisi’s life has been much covered by the world’s media. But what strikes me is the hypocrisy over the Iranian president’s role as the ‘hanging judge’. Families of leftwing political prisoners executed in 1988 have seen his signature on the death sentences issued to their relatives.

In 1988, as these mass executions were taking place, comrade Torab Saleth (formerly of the Fourth International) and I did what we could to draw attention to the horrific events. Virtually no-one in the UK media was interested. With the Iraq-Iraq war just ended, and the UK government looking forward to lucrative economic deals with the Islamic Republic, no-one cared about leftwing political prisoners being butchered. Amongst politicians, the only MP who agreed to see us was Jeremy Corbyn, who listened to us for more than an hour - and the next week used a parliamentary session to raise the issue. However, now that the Islamic Republic is enemy number one, every obituary of Raisi mentions his role during that period. Hypocrisy indeed!

Fall from grace

But his death has been significant in another sense. BBC Persian reminded us this week that almost all of Iran’s heads of state since 1979 eventually fell from grace and faced isolation, exile and even death. It is worth reminding ourselves about that phenomenon.

Mehdi Bazargan: the first (temporary) prime minister after the revolution had complaints about his status and lack of power from his very first days in office. At the time the country had no president, so Bazargan was head of state, yet power was in the hand of the first supreme leader of the Islamic Republic, ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. Bazargan resigned when he faced political obstacles, especially as he was completely sidelined during the November 1979 occupation of the American embassy in Tehran.

Abolhassan Banisadr: after Bazargan’s departure, Khomeini sought the presidency of a layman and trusted ally, who won the election with more than 75% of the votes. His way of managing war affairs and his opposition to the prime minister imposed on him caused much confrontation and conflict. He emphasised the role of the army, while others wanted a greater role for the Revolutionary Guards (IRGC).

The majlis (Iran’s parliament) impeached Banisadr in his absence in June 1981, allegedly because of his moves against the clerics in power (Khomeini himself appears to have instigated the impeachment). Facing death threats, Banisadr fled the country and sought asylum in France.

Mohammad-Ali Rajai: following the dismissal of Banisadr, Rajai was elected president in August 1981. However, his presidency lasted only a few weeks, as he was killed on September 8 in an explosion that also took the life of his prime minister (the People’s Mojahedin Organisation was accused of responsibility for this attack).

Ali Khamenei: he was then elected as the third president of the Islamic Republic in October 1981. He put forward Ali Akbar Velayati as his prime minister, but the Iranian parliament refused Velayati a vote of confidence, and Khamenei agreed to a compromise by offering Mir Hossein Moussavi the premiership. despite strong disagreements with him.

Their tense relationship eventually led to the resignation of Moussavi however. In 1989, the revision of the constitution removed the position of prime minister and Moussavi withdrew from politics for 20 years. (In 2008, he joined the presidential race and he and his supporters claim he won that year’s election. However, the supreme leader sided with his opponent and as a result of this confrontation, which led to the mass Green Movement protests, Moussavi was arrested in February 2009. He has been under house arrest since 2011.)

Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani: became president after winning the 1989 election, and served another term by winning again in 1993. In the 2005 election, he ran for a third term in office, finishing in front in the first round of elections, but ultimately losing to rival Mahmoud Ahmadinejad in the run-off.

Rafsanjani was in favour of a capitalist free market domestically, supporting the privatisation of state-owned industries, and internationally he was regarded as a ‘moderate’, seeking to avoid conflict with the US and the west. He and his family accumulated huge wealth inside and outside Iran during his time in office. According to Iranian officials, he had a heart attack while swimming in his private gym in January 2017, while some of his relatives claim he was actually killed by the Islamic regime.

Mohammad Khatami: he served as president from August 1997 to August 2005. A social reformist with strong support from youth, women and intellectuals, he was elected by almost 70% of voters. However, from the very first months, signs of tension were evident in the upper layers of the government. Khatami later said that his government faced a crisis “once every nine days”.

After the protests that raged in 2007, the publication of his picture in the media inside Iran was forbidden, and the Fars news agency announced that he was banned from leaving the country.

Mahmoud Ahmadinejad: became president in 2005. From messages attributed to ayatollah Khamenei and the clerics close to him, it was understood that the supreme leader had found the most desirable person close to him for the presidency. But this political union did not last long.

Very soon after his election, he appointed Esfandiar Rahim Mashaei as the first deputy, and Khamenei said in a private letter that he did not consider such a choice expedient. Ahmadinejad was out of favour since then and was told by those close to the supreme leader not to enter the next presidential contest.

Hassan Rouhani: his election in 2013 was interpreted by many as a “nuclear referendum”. However, the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) agreement, which stipulated that Iran’s nuclear programme would be entirely peaceful, became a source of tension between him and Iran’s supreme leader after then US president Donald Trump reneged on the agreement. Rouhani and his foreign minister tried to reopen negotiations with the US and EU, but they were openly criticised by the supreme leader.

During his presidency, many accusations of corruption were raised against him and his close relatives. In 2024 he was barred from participating in elections for membership of the Assembly of Experts.

Reaction

What about the other victims of the helicopter crash? Less has been written about foreign minister Hossein Amir-Abdollahian.

During his career, he was close to Iran’s Revolutionary Guards. This allowed him to have direct links with Iran’s regional allies - what are wrongly labelled as Iranian proxy groups (I have written and spoken previously about the complicated relations between Iran and these organisations and states1).

Both Raisi and Abdolahian are now hailed as ‘martyrs’, although I am not quite sure how the result of the accident of a helicopter returning from the opening of a dam can be considered as dying in the cause of religion. But, like everything else in the Islamic Republic nowadays, we have pragmatic interpretations of what constitutes martyrdom.

In the British media, there were contradictory reports about the reaction to these deaths. While the exiled opposition openly celebrated, inside Iran things were more mixed. On social media there were images and short videos of fireworks and celebrations, but Raisi was popular in some smaller towns and the countryside partly because of the subsidies he approved in 2021.

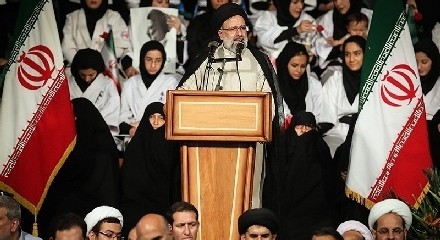

A large crowd of regime supporters did gather for the mourning procession in Tabriz on May 21, but it was nowhere near the five million predicted by the academic who serves as the unofficial spokesperson for the Islamic Republic, professor Mohammad Marandi.

It should be added that the Tabriz Friday Prayer leader, Mohammad Ali Ale-Hashem, who was also killed in the incident, was popular. He was a leader of the Assembly of Experts for Leadership, after winning 834,108 votes - amongst the highest ever in East Azerbaijan province, for which he was the representative.

Most Iranians are aware that Raisi’s death will have little effect in terms of politics or the economy. Repression will remain, and the supreme leader will continue his dictatorial rule with no tolerance of any dissent, at a time when the dire economic situation has impoverished the majority of the population, while at the same time corruption has created astronomical wealth for a small minority associated with the ruling circles.

According to the constitution of the Islamic Republic, in the event of the death of the president, his first deputy,

with the approval of the leadership, assumes his powers and responsibilities, and a council consisting of the speaker of the Majlis, the head of the judiciary and the first vice-president are obliged to arrange for a new president to be elected within a maximum period of 50 days.

That means Mohammad Mokhber Dezfuli. Before becoming the first deputy of Ebrahim Raisi, he was for nearly 15 years head of the ‘Farman e Imam’, one of the richest economic groups in the Islamic Republic. Farman e Imam operates directly under the supervision of the leader of the Islamic Republic and is not accountable to any institution.

Dezfuli as first vice-president of Iran took over the role of organising Iran’s economy, although the evidence shows that he did not have a successful record. He is likely to be a candidate and front runner in the forthcoming presidential elections (June 28). After the Iran-Iraq war he became the CEO of the Dezful Telecommunication Company in Khuzestan province, where he was deputy governor for a period.

Later he moved to Tehran and assumed important positions, such as the deputy of transportation and commerce of the foundation for the dispossessed (Bonyad Mostazafan). He has also been the chair of the board of directors of Sina Bank, which operates under the supervision of the Mostazafan Foundation.

But the most decisive leap of Dezfuli occurred when Ali Khamenei appointed him head of the executive of Farman e Imam in July 2006. This conglomerate was established on the orders of Ruhollah Khomeini one month before his death. It was responsible for the management of the property at the disposal of the leader of the Islamic Republic, including what was confiscated after the 1979 revolution.

Of course, Dezfuli’s chances of winning in June depends on who the supreme leader favours for the post. The remaining key candidate is Mojtaba Khamenei, the supreme leader’s son, who is also a conservative cleric with a background in the Revolutionary Guards. Despite his extensive experience behind the scenes, his limited public and international profile is viewed by some as a disadvantage.

Nevertheless, conspiracy theorists claim the helicopter crash was no accident. They blame Mojtaba Khamenei and his supporters in the Revolutionary Guards.