29.02.2024

The wealth of nature

Despite tailing the climate crisis movement, some on the left still think of labour as the source of all wealth. Jack Conrad spells out the ABCs for the SWP and the IST

For years, for decades, Socialist Worker carried this formulation in its ‘What we stand for’ column: “Workers create all the wealth under capitalism. A new society can only be constructed when they collectively seize control of that wealth and plan its production and distribution according to need” (Proposition one). And - no surprise - the Socialist Workers Party’s dozen or two imitators and clones, organised into the International Socialist Tendency, loyally, crassly, present their own version of this bullshit.

Five examples:

1. In the United States the now liquidated International Socialist Organization: “Workers create society’s wealth, but have no control over its production and distribution. A socialist society can only be built when workers collectively take control of that wealth and democratically plan its production and distribution, according to present and future human needs instead of profit.”1

2. Its diminutive IST rump, Marx 21, likewise declares: “We believe that workers create all the wealth under capitalism, which is a system run by a tiny, wealthy elite. A new society can only be constructed when we, the workers, collectively seize control of that wealth and plan production and distribution according to human need.”2

3. Up north, in Canada, the International Socialists have: “Capitalist monopolies control the Earth’s resources, but workers everywhere actually create the wealth.”3

4. Down under, in Australia, there is Solidarity: “Although workers create society’s wealth, they have no control over production or distribution.”4

5. Then, finally, in terms of our brief IST survey, we have Workers’ Democracy in Poland (formerly Socialist Solidarity). In line with the others we are told: “While workers create social wealth, they have no control over the production and distribution of goods. In pursuit of increasing profits, global capitalism, cultivated by corporations backed by the power of the strongest and richest countries in the world, leads to a progressive stratification of income.”5

Our polemics

When it comes to the SWP mothership, one can presume that our repeated polemics on this issue had an effect. A few years ago there was a forced tweak in Socialist Worker. Its ‘What we fight for’ column now reads: “Under capitalism workers’ labour creates all profit. A socialist society can only be constructed when the working class seizes control of the means of production and democratically plans how they are used.”

However, having just read the first in what is a series of unsigned ‘What we stand for’ articles in Socialist Worker, it is clear that, while there has been a change of words, there has been no change of heart.6 Nature is nowhere to be found, is missing, once again goes unseen.

Hence this question: “Where does wealth come from?” Answer: “Wealth under capitalism appears as a collection of stuff - commodities.” Workers, of course, produce that “stuff” using the means of production owned by the capitalist class and are therefore “key ‘wealth creators’”.7

For those unacquainted with the ABCs of Marxism, all these SWP and IST formulations might appear perfectly acceptable. Yes, they are superficially anti-capitalist and apparently militantly pro-worker. But, as we have repeatedly argued, there is a problem. It lies not with the call for the working class to “collectively seize” control of the wealth they create and then “plan its production and distribution”. No, the programmatic poverty, the economism, of the IST tradition announces itself in the very first sentence: “Workers create all the wealth under capitalism” … or words to that effect.

The fault is twofold. Firstly, the IST statements are simply wrong. Workers do not create all wealth under capitalism. Secondly, it treats workers merely as wage-slaves, the producers of commodities - not feeling, thinking, emotional human beings - a mirror image of capitalist political economy, in other words.

Let us discuss wealth. To do that we must flesh out some basic concepts. Every reader will know Marx’s formula: M-C-M’: M standing for money, C for commodity and the vital ‘ for the extra, the surplus - the profit made at the end of each circuit. In the embryonic form of mercantile capitalism, the secret of making something out of nothing is to be found in the existence of distinct ‘world economies’. A ‘world economy’ being an economically autonomous geographical zone, whose internal links give it “a certain organic unity” (Fernand Braudel).8

The merchant’s ships, wagons and pack animals join and exploit each separate ‘world economy’. Eg, Muslim Arab traders bought cheap in India and China, and sold dear to Christendom (Byzantium and the feudal kingdoms, principalities and city states of Europe). Merchants parasitically acted as intermediaries between such spaces. Mark-ups on spices, silks and ceramics were fabulous - way beyond the cost of transport. There were no socially determining capitalist relations of production. Unequal exchange was the key to the merchant’s wealth and capital accumulation.

Under fully developed capitalism, however, surplus value derives from the surplus labour performed by workers during the process of production. Hence this (extended) formula for the circuit of money: M-C … P … C’-M’.

Through repeated enclosure acts, state terrorism and relentless market competition, the direct producers are separated from the means of production. Peasants and petty artisans fall into the ranks of the proletariat and have to present themselves daily, weekly, monthly for hire. It is that or destitution, hunger and eventual starvation.

Yet on average, we can assume, especially for the sake of the argument, that capital purchases labour-power at a ‘fair’ market price. As sellers of that commodity - labour-power - workers receive back its full worth. Again on average; again for the sake of the argument. Wages then buy the means of subsistence necessary for the production and reproduction of themselves as a wage-slave. Only as human beings are they robbed.

However, capital, because it is only interested in self-expansion, would compel workers to work for 24 hours a day and seven days a week if such a feat were physically possible. Nor has capital, again as capital, any concern for the commodity created by the combination of labour-power, the instruments of labour and raw materials - albeit brought together under its auspices. The resulting commodity could be of the highest possible quality or complete rubbish. But, as long as it sells, and sells at a profit, that is what counts. Hence, for capital, wealth comes in the form of value, surplus-value and above all money. In other words, exchange-value.

Of course, for capitalists, as individuals, wealth also comes in the form of use-values. Despite the myths of Max Weber and the so-called Protestant work ethic, no-one should imagine them living an ascetic, self-denying existence. Especially given this - the second ‘gilded age’ - they have never had it so good.

The super-rich indulge themselves … and often to extraordinary excess. Private islands, football clubs, famous art works, superyachts, rocketing off into near space and flitting by from one palatial residence to another. Even philanthropy and charity-mongering is a form of extravagant consumption by which the elite feed their already grossly overinflated egos (and divert attention away from the grubby side of their businesses). Think of Bill Gates, George Soros and Warren Buffet.9

When it comes to more commonplace CEOs, they consider corporate jets, chauffeur-driven cars, English butlers, Filipino maids, Saville Row suits, vintage wines, trophy wives and the right to grope female employees as perks of the job (yes, most are male, sociopathic and aggressively self-entitled10). Meantime, nearly half the world’s population live on less than $5.50 a day11 and a third have no access to safe drinking water.12

Either way, while for capital, wealth is self-expanding money or value, for the human being, wealth is use-value - what fulfils some desire, what gives pleasure, what is useful. Because use-value so obviously relies on subjective judgement, Marx quite correctly gave the widest possible definition. Whether needs arise from the “stomach or from fancy” makes no difference.13

Use-value is therefore not just about physical needs: it encompasses the imagination too. Indeed, a use-value may be purely imaginary. Its essence is to be found in the human being rather than the “stuff” itself. The consumer determines use-value (ie, utility). Obviously use-values are bought on the market for money and come in the form of commodities produced through the capitalist production process.

However, capital not only has an interest, a drive, to exploit labour and maximise surplus labour. In pursuit of profit, capital also seeks to maximise sales and therefore to expand consumption. Capitalists, in department I, sell raw materials and the instruments of labour to other capitalists: steel, electricity, machine tools, computer chips, etc. Capitalists in department II sell the means of consumption to other capitalists … and to workers too (food, clothing, housing, drink, etc). While the individual capitalist, the particular capital, attempts to minimise the wages of the workers they employ, capital as many capitals, capital as a system, pushes and promotes all manner of novel wants and artificial needs.

Hence celebrity endorsements, influencers and the huge advertising sector, which works day and night to transform the “luxury goods of the aristocracy into the necessities of everyday life”.14 That, and the class struggle conducted by workers themselves, combine to constantly overcome the barrier represented by the limited purchasing power of the working class. Part of what the working class produces is therefore sold back to the working class … and historically on an ever-increasing scale.

That way, workers manage to partially develop themselves as human beings. Not that their needs are ever fully met. There is a steady stream of the latest must-haves. Capital, capital accumulation and the lifestyles of the rich always run far ahead. The lot of the working class therefore remains one of relative impoverishment and “chronic dissatisfaction” (Thorstein Veblen).15

Workers and capitalists alike consume use-values that come in the form of commodities and from the sphere of capitalist relations of production and the exploitation of wage labour (there are, though we shall not explore it here, non-commodity use-values, such as domestic labour - cleaning, cooking, looking after the kids, maintaining the car, putting up shelves, decorating, etc).

Doubtless, once again workers and capitalists alike also consume some commodities that, directly or indirectly, come from peasant agriculture, the individual trader or the self-employed artisan. Such little businesses produce use-values and therefore, by definition, wealth too. With that in mind - and there are millions of them in Britain alone16 - it is surely badly mistaken then to baldly state that “workers create all the wealth under capitalism”.

First paragraph

In theoretical terms, forgetting, passing over, petty bourgeois commodity production is a mote, a mere speck of dust in the eye. There exists a beam, however.

In his Critique of the Gotha programme Marx is quite explicit: “Labour is not the source of all wealth.”17 There is nature too. Marx writes here against the first paragraph of the draft programme of the newly established German Social Democratic Party. It has a strangely familiar ring. A ghostly anticipation of the IST: “Labour is the source of all wealth and culture and, since useful labour is possible only in society and through society, the proceeds of labour belong undiminished with equal right to all members of society.”

Some necessary background. The Gotha unity congress in 1875 represented an unprincipled unification, joining together Lassallean state socialists and the Eisenachers - the followers of Marx, led by August Bebel and Wilhelm Liebknecht. Marx supported unity, yes, but not unity which involved weakening the programme. Note, the Lassalleans, not least because of their dictatorial internal regime, were in steep decline - their trade unions broke away and various splits joined the Eisenachers.

However, the Eisenachers did make unwarranted programmatic concessions: eg, “producer associations assisted by the state ...”. Not in itself a disaster, but the central role accorded to the state and state aid nostrums left the door ajar for a “Bonapartist state-socialist workers’ party” (Engels 1887-88).18

It should be added that Marx was probably eager, primed, itching to write his Critique due to Mikhail Bakunin. In his Statism and anarchy (1873), the founder of modern anarchism portrayed Marx as a German nationalist and an “authoritarian” worshipper of state power. Not only that: Marx was said to have been responsible for the programme and every step taken by the Eisenachers since day one. Eg, “The supreme objective of all his efforts, as is proclaimed to us by the fundamental statutes of his party in Germany, is the establishment of the great People’s State (Volksstaat)”.19

As a canny political infighter Marx chose to point the finger of blame at Ferdinand Lassalle (1825‑64). Lassalle was the real German nationalist and worshipper of state power. He had secretly offered to do a deal with Otto von Bismarck. That way, the Bismarck state would have gotten its “own bodyguard proletariat to keep the political activity of the bourgeoisie in check”.20

Marx, therefore, credited Lassalle with being the spiritual father of the Gotha programme, including the above-quoted first paragraph. Unfair, perhaps - Lassalle was dead, killed in a silly duel. More to the point, Marx’s own pupils - ie, August Bebel and Wilhelm Liebknecht - were quite capable of making elementary blunders, such as forgetting nature, all by themselves. No help, no prompting from Lassalle and his state socialists was needed. But, by blaming Lassalle, Marx was able to give his comrades an escape route - a route which, if taken, would simultaneously save their blushes and draw a clear line of demarcation against Lassallean state socialism.

None of the SWP’s leaders, past or present - eg, Tony Cliff, Duncan Hallas, Chris Harman, John Rees, Lindsey German, Martin Smith, Alex Callinicos, Charlie Kimber and Amy Leather - were cribbing from Lassalle ... or Bebel and Liebknecht for that matter. That much is obvious. No, we have a clear case of historical reflux, opportunism recurring, economism spontaneously regenerating - as it inevitably does, given the material conditions of capitalism and the oppressed position of the working class.

Incidentally, economism needs defining here - that is, if we are going to have an informed discussion. Economism is, in essence, a bourgeois-imposed outlook, which restricts, narrows down the horizons of the working class to mere trade unionism … that or, more commonly, it simply denies or belittles the role of high politics and democracy in the struggle for socialism. And, regrettably, the IST and its SWP mothership are hardly alone.

Economism is the dominant outlook of today’s left. Not, of course, that economism denies politics. The problem is that, when the economistic left takes up politics, it is not the politics of the working class - ie, orthodox Marxism - no, instead it is the politics of other classes and other ideological trends which they promote: left social democracy, pacifism, greenism, feminism, black separatism, petty nationalism, etc.

Back to Marx

Anyway, back to Marx. In 1875, he savaged the “hollow phrases” in the Gotha programme about “useful labour” and all members of society having an “equal right” to society’s wealth. There is useless labour - labour that fails to produce the intended result. People are not equal, etc, etc.

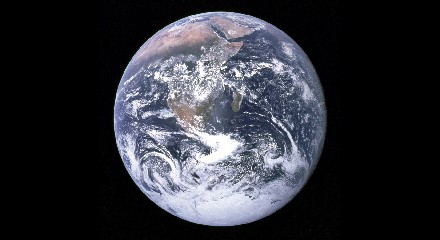

More to the point, at least when it comes to our main concern here, there is nature. Marx wrote this: “Nature is just as much the source of wealth of use-values (and it is surely of such that material wealth consists!) as labour, which itself is only the manifestation of a force of nature, human labour-power.” Marx goes on to explain that, “insofar as man from the outset behaves towards nature” - what he calls the “primary source of all instruments and objects of labour” - as an “owner, treats her as belonging to him, his labour becomes the source of use-values, therefore also of wealth”.

The same metaphor occurs elsewhere again and again in order to depict the two-sided source of wealth. Eg, in Capital, Marx approvingly quotes William Petty: “Labour is its father and the earth its mother.”21 Leave aside the gendered language - which I find totally unproblematic, especially given the primacy rightly given to the female sex and in turn nature - the thing that must be grasped here, is the two-sided source of wealth. Sunshine and water, air and soil, plants and animals are all ‘gifts from nature’.

Human beings too are part of nature and, just like every other living thing, rely on nature in order to survive. However, humanity applies itself to nature, although in the process of production we often bank on the direct actions of nature. Eg, though a natural product, wheat is selected, sown and harvested by labour; yet it germinates in the soil and needs both rain and sunshine if it is to grow and duly ripen.

So the two forms of wealth conjoin. Yet, despite that, for the laws of capital, what gives the wheat value is not what is supplied by nature. That has use-value, but not value. Value derives from the application of labour-power alone.

There is another - a spiritual, or artistic - dimension to the use-value of nature that should never be underestimated:

There is a pleasure in the pathless woods,

There is a rapture on the lonely shore,

There is society, where none intrudes,

By the deep sea, and music in its roar:

I love not man the less, but Nature more.

(George Gordon, Lord Byron, Childe Harold’s pilgrimage - 1812)

Leave aside enduring memories of long countryside walks in the Scottish highlands, the Lake District and places further still. Just looking out over London from my frontroom window each morning and seeing the sunrise, the bright blue sky, the gathering storm clouds, even the drab grey and mists inspires me. Walking on Hampstead Heath, picking blackberries, seeing the first signs of spring, glimpsing the occasional urban fox, following the nesting swans and the progress of their cygnets, the swirling, ever changing patterns of migrating starlings, the flashing lime green of the darting parakeets brings me joy. Turning from my computer, to admire the sunset, as I work in my office in the evening, humbles me too. In the big scheme of things I’m insignificant, I’m transient, I’m just a little part of nature.

Sorry are those who experience no such feelings. They are impoverished. So, surely, wealth cannot be limited to the products of human activity alone. As well as “stuff”, wealth must include every form of consumption which produces human beings in one respect or another.

Michael Lebowitz rightly considered this of particular significance: “Marx’s identification of nature as a source of wealth is critical in identifying a concept of wealth that goes beyond capital’s perspective”.22 Capital, as we have argued, has but one interest - self-expansion. Capital has no intrinsic concern either for the worker … or nature. And, especially over the last 150 years, and increasingly so, capitalist exploitation of nature has resulted in destruction on a huge scale. Deforestation, erosion of topsoils, spreading deserts, CO2, methane and other greenhouse gas emissions - all grow apace. Countless species of flora and fauna have already been driven to extinction. Instead of the cherishing of nature, there is greed, plunder and wanton disregard.

The working class presents the only viable alternative to the destructive reproduction of capital. First, as a countervailing force within capitalism - one which has its own logic, pulling against that of capital. The political economy of the working class brings with it not only higher wages and shorter hours. It is also responsible for health services, social security systems, pensions, universal primary and secondary education … and measures that democratise the environment: eg, the right to roam that came out of the 1932 mass trespass movement and Kinder Scout. Wealth, for the working class, is not merely about the accumulation and consumption of an ever greater range of commodities. Besides being of capitalism, the working class is uniquely opposed to capitalism.

The political economy of the working class more than challenges capital. It points beyond capital - to the total reorganisation of society and, with that, the ending of humanity’s strained, brutalised, crisis-ridden relationship with nature.

Socialism and communism do not raise the workers to the position where they own the planet. Mimicking the delusions associated with capitalism - as witnessed under bureaucratic socialism - brings constant disappointment, ecological degradation and nature’s certain revenge. Humanity can only be the custodian of nature.

Marx was amongst the first to theorise human dependence on nature and the fact that humanity and nature co-evolve. He warned, however, that the capitalist process of production is also a “process of destruction”, because it “tears asunder … disturbs the circulation of matter between man and the soil … therefore violates the conditions necessary for lasting fertility”.23

John Bellamy Foster - basing himself solidly on Marx’s considerable writings on this question - coined the term, “metabolic rift”, to capture the break between nature and the human part of nature.24 Capitalism crowds vast numbers into polluted, soulless, crime-ridden concrete jungles. Simultaneously, the ever bigger farms of capitalist agribusiness denude nature with mono-crops, the ripping up of hedgerows and, as highlighted by Rachel Carson back in the early 1960s, the chemical death meted out to “birds, mammals, fishes, and indeed practically every form of wildlife”.25

The Marx-Engels team wanted to re-establish an intimate connection between town and country, agriculture and industry, and rationally redistribute the population. Mega-cities are profoundly alienating and inhuman. The growth of ever-sprawling conurbations has to be ended and new spaces made inside them for woods, parks, public gardens, allotments and small farms.

Short-termism

Doubtless, while this programme has great relevance today, not least given the almost countless reports - eg, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and its code-red warning about the world approaching a tipping point - it is hard to imagine the capitalist class, with its short-termism and manic fixation on profits, willingly going along with the far-reaching measures that are needed to avert ecobarbarism. Under the conditions of socialism and communism that would surely be another matter entirely.

Our aim in the CPGB is not only to put a stop to destruction and preserve what remains. Of course, the great rain forests of Congo, Indonesia, Peru, Columbia and Brazil must be safeguarded. So too the much depleted life in the oceans and seas.

However, more can be done. The riches of nature should be restored and where possible enhanced. Grouse moors and upland sheep farming are obvious prime targets for rewilding in a Britain with its “very striking - and worrying” low levels of biodiversity (Natural History Museum report).26 Wolves should sing again.

But we can think really big. Mesopotamia - now dry and dusty - can be remade into the lush habitat it was in pre-Sumerian times. The Sahara in Africa and Rajputana in India were once home to a wonderful variety of fauna and flora. The parched interior of Australia too. With sufficient resources and careful management they can bloom once more.

The aim of such projects would be restoration, not maximising production and churning out an endless flood of commodities - hardly the Marxist version of abundance. On the contrary, the communist social order has every reason to rationally economise and minimise all necessary inputs.

The “enormous waste” under capitalism outraged Marx. The by-products of industry, agriculture and human consumption are squandered and lead to pollution of the air and contamination of streams, rivers and lakes. Capital volume three contains a section entitled ‘Utilisation of the extractions of production’. Here Marx outlines his commitment to the scientific “reduction” and “reemployment” of waste.27

In place of capitalism’s squandermania there comes with communism the human being, who is rich in human needs. However, these needs are satisfied not merely by the supply of stuff: they are first and foremost satisfied through the medley of human interconnections and a readjusted and sustainable relationship with nature.

-

It was, therefore, genuinely disappointing to read former SWP loyalist Colin Barker. Tasked with defending the ‘Where we stand’ column a couple of decades ago, he wrote a 19-part series in Socialist Worker over the period, December 6 2003-June 26 2004. Naturally he began with proposition one, but - guiltily - he steered clear of nature. He broke with the SWP in 2014 - not over the Respect popular front or even nature: no, it was the rape allegations against former national organiser Martin Smith. Not that Martin Empson’s pamphlet Marxism and ecology: capitalism, socialism and the future of the planet was any better (2009). As an SWP loyalist, Empson tried to do the impossible: square the old ‘Where we stand’ statement on wealth with the Marxism of the Marx-Engels team.↩︎

-

Socialist Worker February 21 2024. Nature, note, is totally absent, gets not a mention.↩︎

-

F Braudel Civilization and capitalism Vol 3, Berkeley CA 1992, p22.↩︎

-

See I Hay and JV Beaverstock Handbook on wealth and the super-rich Cheltenham 2016.↩︎

-

See P Babiak and RD Hare Snakes in suits: when psychopaths go to work New York 2007.↩︎

-

www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2018/10/17/nearly-half-the-world-lives-on-less-than-550-a-day.↩︎

-

www.who.int/news/item/18-06-2019-1-in-3-people-globally-do-not-have-access-to-safe-drinking-water-unicef-who.↩︎

-

K Marx Capital Vol 1, Moscow 1970, p35.↩︎

-

See G Reith Addictive consumption: capitalism, modernity and excess London 2018.↩︎

-

See T Veblen The theory of the leisure class Mineola NY 1994, p20.↩︎

-

In 2021, 5.5 million in fact - see www.fsb.org.uk/uk-small-business-statistics.html.↩︎

-

K Marx and F Engels CW Vol 24, London 1989, p81.↩︎

-

K Marx and F Engels CW Vol 26, London 1990, p500.↩︎

-

See www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1872/housing-question/ch02.htm; the official K Marx and F Engels CW Vol 24, London 1988, p364 leaves “bodyguard” out of its text.↩︎

-

K Marx Capital Vol 1, Moscow 1970, p43.↩︎

-

M Lebowitz Beyond Capital Basingstoke 2003, pp130-31.↩︎

-

K Marx Capital Vol 1, Moscow 1970, pp505-06.↩︎

-

JB Foster Marx’s ecology: materialism and nature New York 2000, piv.↩︎

-

R Carson Silent spring Harmondsworth 1991, p87.↩︎

-

The Observer October 10 2021.↩︎

-

K Marx Capital Vol 3, Moscow 1971, p101.↩︎