14.12.2023

Their Tolkien and ours

Neo-fascist interpretations of JRR Tolkien’s works are resurgent - and understandable. But can the left make room in its culture for hobbits? Paul Demarty revisits The lord of the rings

“Hey, you ever read Tolkien? You know, the hobbit books? His descriptions of things are really good … makes you want to be there.”

So goes a throwaway line in Rian Johnson’s first film, Brick, released a few years after Peter Jackson’s grand trilogy of film adaptations of the Lord of the rings. They are spoken by Lukas Haas as ‘The Pin’, the leader of a drug gang in Orange County, as he gazes into a winter sunset over the Pacific Ocean; The Pin is one of Johnson’s great inventions - a monster selling heroin to teenagers who retains a perfectly childlike, slightly nerdy naivety. For all the ink spilled, in academic and popular commentary, on JRR Tolkien’s work, he gets closest, it seems, to the enduring value of the thing, and its enduring appeal to a mass readership.

Other readings, of course, are available. One has achieved a certain notoriety since the election of Giorgia Meloni as prime minister of Italy. After World War II, Italian fascism regrouped, with the discreet and now notorious assistance of the western powers. Many of its adherents abandoned the heroic modernism of Benito Mussolini and its futurist antecedents; they turned, instead, to a more atavistic and anti-modern mode of thought. Julius Evola, ejected from the Fascist Party for extremism, became a hero. And so, after the publication of the Lord of the rings in the 1950s, did Tolkien. His combination of the heroic epic and the near-pantheistic pastoral inspired a generation of rightwing youth, to the point that several fascist-oriented cultural festivals took place in the early 1980s under the title Campo Hobbit (‘Camp Hobbit’). One of those young militants was a certain Giorgia Meloni, and her affection for these books seems undimmed.1

It was not only the Italians. Tolkien became a big influence on the Norwegian black metal music scene of the early 1990s; and several of those bands swapped their initial adolescent satanism for a Norse-pagan orientation to neo-Nazism. Foremost among these was Kristian ‘Varg’ Vikernes, whose first band was called Uruk-Hai (a species of Orc), while his second was called Burzum (‘darkness’ in the Orcish ‘black speech’), and who went by the stage name, Count Grishnakh (an Orc captain). In an interview in the book Lords of chaos, which despite the far-right leanings of its author remains a crucial document of this bizarre phenomenon, he takes the exact opposite view to the Italian hobbit-campers:

We were drawn to Sauron and his lot, and not the hobbits, those stupid little dwarves. I hate dwarves and elves. The elves are fair, but typically Jewish - arrogant, saying, “We are the chosen ones.” … But you have Barad-dur, the tower of Sauron, and Hlidskjalf, the tower of Odin; you have Sauron’s all-seeing eye, and then Odin’s one eye … So I sympathise with Sauron.2

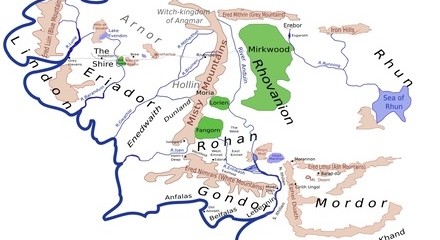

There has not been any equivalent attempt on the left to coopt Tolkien. It is undeniably a harder task, for reasons we will discuss. Instead, controversy rages over whether Vikernes or Meloni have it right: the books present an irremediably racialised portrait of their world. On the face of it, there is plenty of evidence; there are the hobbits, of course - short, stocky Englishmen of a distinctly petty-bourgeois stamp; and the dwarves - prickly, niggardly and great geniuses of engineering (Scottish accents in the films); and the Men (Tolkien’s world is extremely male) - the greatest of heroes and the weakest to the temptations of power. Their allies are the quasi-angelic elves, and their enemies the monstrous and brutal Orcs. The nazgül, technically human antagonists throughout LotR, are described often as the ‘Black Men’. The good races are in the west; the evil in the east. So it goes on.

This may be the wrong angle to look at it, however: an analysis that owes more to the prior framing of Tolkien’s critics than the text as it stands. What is reactionary in the books has relatively little to do with race, but rather the genesis and architecture of the project as a whole. As to whether it can be saved for us: that will be a matter for our conclusion.

Biography and myth

In the high period of literary theory, there emerged a certain suspicion of biographical evidence in the analysis of texts; indeed, this was the crux of Marcel Proust’s objections to the otherwise forgotten critic, Charles Augustin Sainte-Beuve, which eventually metastasised into his vast novel. Yet books require authors; there is no Proust without Sainte-Beuve, and no ‘Middle Earth’ without the peculiar course of Tolkien’s life.

Born in South Africa, Tolkien was raised after his father’s death in the west Midlands countryside by his mother; after her death in turn, he was taken on her wishes into the care of a Birmingham priest, and remained a devout and conservative Catholic for the rest of his life. His family background was solidly middle class, and he attended a minor public school and then a Catholic grammar school. He nonetheless made it to Oxford, studying the classics and English. As for many of his generation, World War I proved a traumatic interruption; he fought at the Somme and, though he escaped unscathed in the end, almost all his close schoolfriends were extinguished in the slaughter on the western front.

He returned, at length, to academia, becoming a formidable scholar of language and literature in historical depth - the way it was done in what used to be called philology. He translated the great Anglo-Saxon epic Beowulf, and in time the seeds were planted for a very particular project: the invention, out of whole-cloth, of an alternative mythical tradition for England - a process he called mythopoeisis.

Parts of it were circulated in the Oxford academic scene. Most famously, an informal grouping called ‘the Inklings’ began to gather in the upper room of the Eagle and Child, an Oxford pub, to read to each other. Besides Tolkien, their most famous member was CS Lewis; but it could be a demanding audience (at yet another long reading of Middle Earth material, Hugo Dyson, famously lamented: “Not another fucking elf!”).

The first published portion of the Middle Earth mythos, The hobbit, began as stories he told his children; the Lord of the rings was written over nearly two decades. During that time, of course, a second world war was fought out, which would prove even more bloody than the first. His only part in the affair was as a code-breaker; and he remained cloistered at Oxford until his retirement, living the rest of his life in Bournemouth. In that time, his fiction had become enormously successful, but he did not take readily to fame and lived quietly until his death in 1973.

Tolkien’s biography, then, is one of a particular kind of upwardly mobile, middle class scion; a glancing blow at the colonies, a crooked course between rural and urban England, and a long career as a ferociously talented academic in a field that barely outlived him. When he was born, the British empire remained at roughly the greatest extent it would ever reach; when he died, it was just about gone altogether. He was less than a decade younger than the first practical machine gun, and matured just in time to see that weapon’s gruesome coming-out party up close. His day job of literary archaeology, and indeed his religious traditionalism, offered some escape from the industrial slaughter he had witnessed. Yet his books are documents of both, sometimes in sudden and jarring contrast, along with a profound, rather idealised love of nature and rural life. Faced with a choice between nostalgia and facing the horrors of 20th century warfare squarely, Tolkien picked both.

That perhaps accounts for the structural oddity of the books. They would, ironically, never make the cut as works of commercial fantasy today. They do not play by the rules which they are supposed to have invented. The hobbit and The fellowship of the ring are, in particular, extremely episodic. Guillermo del Toro, who was initially slated to direct the Hobbit films, defended his decision to make two pictures out of that one slender volume: there was, you see, a point in the middle where, if you open the book and lay it flat, you have two movies right there - one on the left and one on the right. That is true enough, but there are very many such points (indeed, Peter Jackson eventually stretched it out to three).

The heroes get into trouble, and rapidly out of it; peril alternates with rhapsodic description and long stretches of dwarven singing. It is, ironically, only after the killing of the dragon, Smaug - ostensibly the whole point of the affair - that any real, sustained narrative tension develops, when a fight rapidly brews over who gets to keep all that gold. (God is strangely absent from this devout writer’s works, but original sin is everywhere.)

One such ‘episode’ - the hobbit Bilbo Baggins’ discovery of a magic ring, which does not have any particular importance beyond giving its wearer the power of invisibility - is then given immense importance in its central role in the Lord of the rings. (Among the many dark arts of genre fiction, Tolkien can justly be credited with the invention of retconning.) This whimsical little MacGuffin suddenly became a demonic force with a mind of its own, which deliberately ‘found’ Bilbo as a way of returning to its master, the plainly Satanic Sauron, corrupting the souls of all who possess it.

Perhaps all this is the genius of the mythopoetic method. After all, epics revise each other; the sack of Troy in Homer’s Iliad propels Aeneas, at length, to western Italy, where his descendants can found Rome, per Virgil’s Aeneid. It may be difficult to remember whether Bilbo and his companions are accosted by trolls before or after Bilbo finds the ring; but then, casual readers of the Odyssey are unlikely to remember whether the Greeks encounter the Sirens or Circe first of all. Those epic poems, after all, are necessarily episodic, having likely been largely disseminated orally in chunks before being compiled into a longer text.

Accidentally or otherwise, Tolkien captures that mythic character well; and that contributes to the reader’s experience of being taken out of everyday experience - the great high that launched a million high-fantasy imitators over the ensuing decades. These are novels inasmuch as they are fictional narratives roughly the same size and shape as other contemporary examples. (As Randall Jarrell put it, “A novel is a prose narrative of some length with something wrong with it.”) Yet reading them is, in terms of narrative rhythm, far more familiar to readers of the ancient epics that were the staples of the classically-educated Oxford dons of Tolkien’s day.

Epic Pooh

This obstreperously backward-looking character naturally incurs the suspicions of leftist commentators. Paradigmatically, there is Michael Moorcock’s legendary essay ‘Epic Pooh’, which castigates several authors of high fantasy, of whom Tolkien is unquestionably the greatest (and takes up the largest part of Moorcock’s attention). His title indicates his starting point - that the authors he discusses write in an infantilising fashion, imposing childishness on the reader:

The sort of prose most often identified with ‘high’ fantasy is the prose of the nursery room. It is a lullaby; it is meant to soothe and console. It is mouth-music. It is frequently enjoyed not for its tensions, but for its lack of tensions. It coddles; it makes friends with you; it tells you comforting lies.3

Moorcock directs many barbs Tolkien’s way - he delights in the unintentional humour of words being taken “seriously, but without pleasure”, mischievously citing the wonder of the Shire hobbits at Frodo’s decision to “sell his beautiful hole”. But, above all, his Tolkien is an English petty bourgeois; his anti-urban outlook is inseparable from the fear of the mob by

a fearful, backward-yearning class for whom ‘good taste’ is synonymous with ‘restraint’ (pastel colours, murmured protest), and ‘civilised’ behaviour means ‘conventional behaviour in all circumstances’. This is not to deny that courageous characters are found in The lord of the rings, or a willingness to fight Evil (never really defined), but somehow those courageous characters take on the aspect of retired colonels at last driven to write a letter to The Times and we are not sure - because Tolkien cannot really bring himself to get close to his proles and their satanic leaders - if Sauron and co are quite as evil as we’re told. After all, anyone who hates hobbits can’t be all bad.

Moorcock’s essay is brilliant, above all for being wickedly funny, and for coming from a partisan position in favour of a widely derided genre of fiction. He is, of course, a fantasy writer himself, and perhaps justly concerned that the torrent of Tolkien imitations which began in the 1970s were giving everyone a bad name. I think he misses the genius of Tolkien, however, because he cannot really understand why anyone would idealise a lost rural idyll - for him, it is always a matter of an atavistic childishness, the return to the hundred-acre wood - “the woods that are the pattern of the paper on the nursery room wall”. He rejects the idea that modernity, with its attendant urbanisation, denies access to the countryside - after all, can the Londoner not get a train in any direction and end up somewhere wild and beautiful?

This seems both to get the point and somehow by doing so to miss it completely. The Shire - which takes up perhaps a hundred pages between The hobbit and The lord of the rings - is a portrait of a society, not a landscape. It is one thing to spend a couple of hours on a sunny Saturday admiring the South Downs - I did it many times when I lived in the capital - but another thing to farm it. The woods on the nursery wallpaper are the negative image of the alienation of mass capitalist society. Those who find Tolkien’s picture too twee can consult the sombre history in folk songs and other popular art of the trauma of the enclosures and the herding of people into cities to be near-enslaved by mill-owners, or of the Irish masses scattered to all the corners of the earth by the great famine. The historical-theoretical record is known to Marxists from the long chapter in Capital on ‘primitive accumulation’.

Grim darkness

There is more to Tolkien’s critique than that, however. His ‘mobs’ - most obviously the uruk-hai - are themselves manufactured, and manufactured specifically to kill. The morbid feats of ingenuity of Saruman - Gandalf’s wizard superior whose treachery occupies much of the first half of the Rings - are bought at the price of vast ecological devastation, the clear-cutting of forests and poisoning of rivers. (The quite horrifying portrait of Saruman’s war factories is one of the few things Peter Jackson’s movie trilogy gets very right about the novels.) Modernity, for Tolkien, is no mere aesthetic matter - of snapdragons being displaced by smoke-belching furnaces. There is an intimate and indissociable relation between the gleeful destruction of nature and mechanised warfare - of the sort that Tolkien saw first-hand on the western front in 1916, and which unfolded as he wrote in 1939-45.

And so, parallel to the urban-rural distinction, Tolkien mobilises another opposition - between the modern methods of total military mobilisation and a pre-modern vision of military virtue, itself not quite ancient and not quite medieval. It is as if Odysseus, Beowulf and Sir Gawain were to find themselves at the front in the Somme.

It will not be too much of a spoiler to note that in the end the heroes of old triumph against the products of the war machine. Yet the tone is not triumphalist, but elegaic. Gandalf, and other immortals, never doubt that their struggle represents the end of an age, after which they must finally depart and make way for the ‘age of men’, and so it proves. The strange episode of ‘the scouring of the Shire’, right at the novel’s end, in which Saruman repeats his economic violence in the hobbit heartlands, indicates what that future may hold. Tolkien, then, is too much of a romantic to suppose that there is any reason that we will get back to the nursery room and, whatever his lies are, they are not comforting.

It is this that makes him great, and the likes of Terry Brooks and David Eddings intermittently enjoyable trash. The fashion in high fantasy shifted in the 1990s, after the success of George RR Martin’s A game of thrones, in a darker direction - the word ‘grimdark’ has ended up being thrown around a lot. (It comes from the science-fiction-Tolkienesque tabletop wargame Warhammer 40,000, whose tagline once read: “In the grim darkness of the far future, there is only war.”) The differences between Martin’s work and Tolkien’s need hardly be mentioned. Yet the ‘grimdark’ turn in high fantasy is less anti-Tolkienesque (as was the case with China Miéville’s breakthrough novels) but revisionist-Tolkienesque.

One striking commonality among many of the darker fantasy series of recent years is that they are allegories of the collapse of feudal societies into early-modern ones, and draw much of their horror from faithful fictionalisations of the attendant mass violence. That is true of Martin’s A song of ice and fire, with which A game of thrones began, of Joe Abercrombie’s First law, and Daniel Abraham’s The dagger and the coin. It is right there in the Rings, in the end of the Third Age; just as the closing of the frontier haunts the westerns of the classical Hollywood era, but is brought out in violent moral ambiguity in the great revisionist westerns of the 1960s and after.

That is the respectable part of the legacy of Tolkien’s two published novels. The less respectable part is - well, Brooks, Eddings, Dungeons and dragons (until the pen-and-paper role-playing game scene matured, and particularly the great D&D computer games put out by Black Isle at the turn of this century) - and so on ad infinitum. I am, again, a happy enough consumer of this sort of thing, as I am of burgers and cheap lager. Yet they are characterised by, on the one hand, perfectly machine-tooled narratives - however complex they may become over the course of long series of novels - that are little more than fictionalisations of Joseph Campbell’s Hero with a thousand faces - and, on the other, vast overinvestment in endless world-building and lore. (Starting with 1977’s Sword of Shannara, Brooks produced not less than eight novels and seven series with names ending in “of Shannara”.)

This tedious pattern has, at length, spread into the wider culture. We need only think of the ‘Marvel cinematic universe’ - or is it now the Marvel cinematic multiverse? - which is just possibly now reaching the point of total soil exhaustion. Even the gloriously absurd gun-fu vehicle, John Wick, went down this useless path over the course of its sequels, with this year’s bloated and tiring fourth instalment hopefully to prove the last.

But Tolkien was patient zero for this sort of thing. His private papers included vast quantities of such lore, of course - the whole thing had begun as an experiment in invented languages and cultures - which he was not minded to publish. His son and literary executor, Christopher Tolkien, was not so circumspect, and we have had no end of inessential material sluiced into bookshops, including commentaries by Christopher himself.

To that we may add Jackson’s Lord of the rings movies, which are fine enough pieces of work on their own terms, but basically straightforward action flicks that miss nearly all of the ambiguities of the source material, and from that point of view amount to megabudget fan fiction; and his Hobbit movies, which drag that cute little book out to three interminably prolix epics, largely by ladling on extra lore from The Silmarillion and elsewhere. This is very much industrial culture - there is no Shire quite so scoured as Tolkien’s imagination. That is what the overproduction of lore gets you: endless excuses to create more, more, more, and the consequent diminishment of the original articles to mere trifles in a Borgesian library of infinite dimensions, but infinitesimal worth.

A worthwhile leftwing reckoning with Tolkien’s work must confront both these aspects: the strange, meandering, barely-even-novels on which his reputation as a writer stands, and the hypertrophic production they ultimately unleashed. (Not for nothing did some wiseacre on a long-forgotten Usenet group come up with the phrase, “extruded fantasy product”, to describe the endless pulpy Tolkienesques.)

Romantic

If we must make an ideological diagnosis of the Rings, we should call it reactionary-romantic - a preference for the rural over the urban, the artisanal over the industrial, the supposed organic unity of pre-modern societies over the double-freedom of anonymous capitalist society. Because it is a serious example of that outlook, whose mass success in spite of its narrative clumsiness and donnish archaisms is something like a black swan event, its critique is bracing and provocative, if we want to hear it - just as Marx admired Balzac’s reactionary novelistic critique of the French bourgeoisie. The wide but shallow ‘lorescapes’ that followed in the Rings’ wake - from Shannara to the MCU - are of interest largely as symptoms of a capitalist culture wholly extractive in nature.

A certain parallel is offered by the case of Richard Wagner - politically speaking now known largely as a vicious anti-Semite, but also (when liberalism, nationalism and socialism were not so easily teased apart as they were to become) a revolutionary of 1848. Tolkien disclaimed any inspiration from Wagner’s Der Ring des Nibelungen, but the parallels are striking with the Middle Earth novels as a whole: we find cursed magic rings, grim mechanised labour, dragons jealously guarding treasure, and all the rest. George Bernard Shaw, in his pamphlet The perfect Wagnerite, described Wagner’s opera cycle as a progressive version of that story of Age passing into Age: the overthrow of the gods of the old world by Man.4 It was not merely a fancy of Shaw’s: in 1912, the German Social Democratic Party celebrated an electoral advance by producing a postcard depicting “the Red Siegfried” slaying a dragon and securing victory in “the electoral battle”.5

Wagner is rather less persuasively coded as a progressive these days, after his cooptation by Hitler’s regime, and also his absorption at length into the conservative classical music canon (learned music critics at the time were largely baffled by his bombast and alleged crudity - a point taken mischievously as a recommendation by Shaw). That is no reason to let him go easily - nor Tolkien. After all, Meloni and her fellow hobbit-campers cannot even agree with Varg Vikernes as to why Tolkien should be so inspirational. Are the immigrants the Orcs, or the ‘patriots’? Who cares, provided we get our revenge? So long as capricious gods rule over us, we will have need of Wagner; and, so long as humanity devours the rest of nature to produce the means of mass death, there will be something for us in Tolkien.

His descriptions of things, after all, are really good: they make you want to be anywhere other than here.

-

M Moynihan and D Søderlind Lord of chaos Washington 1998, p162.↩︎

-

warwick.ac.uk/fac/arts/english/currentstudents/undergraduate/modules/en361fantastika/bibliography/2.7moorcock_m.1978epic_pooh.pdf.↩︎

-

www.dhm.de/lemo/bestand/objekt/wahlpostkarte-der-spd-1912.html.↩︎