11.05.2023

Part of the stream

MS Kia Sliding into revolution: a doctor’s memories of life, love and revolution Lulu 2022, pp330, £14.96

As the title of his book suggests, comrade MS Kia slid, along with many of his fellow citizens, into the 1979 revolution in Iran. He writes in an observer-philosopher style, with pungent comments and witty remarks. It is like listening to an old friend.

Also, however, this is an excellent primer in how naive youth and a divided left - not to mention those who wanted to climb the greasy pole and eventually became pawns of the regime - all combined in the process leading to the end of the dream of a free, democratic state. Historically, the book looks in some detail at the long fight to overthrow the autocratic regime of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the shah, which for the left had the aim of opening the road to socialism - only for them to be out-manoeuvred by the mullahs.

Kia interwinds his family and friends throughout. The first few chapters speak in some detail about his family. I was taken by his father, who fell in love at the age of seven with the girl he eventually married and was in love with to the end of both their lives. Kia says the males of his family were mullahs (something, he says, he has in common with Karl Marx, who was also raised in a family imbued with religion) and he describes his childhood as idyllic, with a loving mother who soothed his burns (literally).

Kia says that his father “was and remained too honest for the Iran the shah was building”, and the family moved to Britain for a short time during the drive by the widely popular government headed by Mohammad Mosaddeq to nationalise the western-owned oil companies (legislation to that effect was passed in 1951). Kia recounts being beaten up during the morning break by boys at the primary school he attended in Manchester, because he was “stealing our oil”. He learned to run away.

The family moved several times. Back to Teheran, then to Istanbul, Vienna, Munich and finally back to England, where he was fondled in the boarding school he attended after being caned by both the headmaster and the English teacher. Once he started university, religion soon disappeared from his life, as he found it was “no longer necessary to explain anything”. He says that the boarding school prepared him well for the imprisonment he would suffer back in Iran.

Medical school

In medical school he became politically active, joining the National Front founded by Mosaddeq, and the Iranian Students Association, the main student anti-shah organisation.

Comrade Kia has a sly sense of humour and likes telling amusing stories. For instance, a friend of his pretended to be a doctor for years in order to marry a wealthy young woman. He ‘went to work’ every day with a stethoscope and claimed he was ‘on call’ in the hospital he worked at. Exactly what happened to him is never spelled out.

Which leads me to two confusing aspects of this book. One is the plethora of people’s names. Sometimes they come in and out of chapters which makes following the narrative difficult. The other is the transliteration of Farsi words into English - not translating them, but giving their pronunciation. Precisely how this is supposed to help our understanding I am not sure, but for people without Farsi (like me) it sometimes makes reading a little difficult.

Politics is, however, at the centre of the book. The changes in the shifting groups on the left, for instance, of which there appeared to be many. He gives, as an example, a student he knew well who went from the ‘official communist’ Tudeh Party (set up in 1941 after the Communist Party of Iran was banned), through a pro-Mao breakaway after the Sino-Soviet split, and finally, after being arrested and spending five years in jail, gave up on the working class struggle, thanks to the shah’s series of reforms in the 1960s, known as the ‘White Revolution’. This did not stop him being shot as soon as the Islamists took power. How and why he completely changed his politics we never discover, though Kia has ideas about it from his own prison experiences in the early 80s.

Kia returned - now as a qualified doctor - to Iran. He discovered that the shah had decided that all civil servants and state employees like himself had to join the Rastakhiz - the only legal political party from 1975-78. When asked how those who did not wish to join would be treated, apparently the shah replied that they were ‘free to leave the country’. In the meantime armed struggle had been taken up by the revolutionary Fadai, Mojahedin and others. The human toll was high - through death in combat, execution, imprisonment, exile, etc.

Comrade Kia decided not to join the shah’s party, and happily this infraction was ignored by the authorities. But he felt, in his inner soul, that a revolution was coming. As he says, “For a century people in my country had been denied their two basic demands: the quest for freedom and for independence from foreign interference.” He describes in detail the US-UK organised army coup against the democratically elected Mosaddeq in 1953, the connivance of the clergy, the passivity of Tudeh and the return of Pahlavi as an absolute monarch determined to modernise the country from above. Launched in January 1963, his ‘White Revolution’ broke the back of the feudal landlords and propelled Iran into capitalist development and dependence on a USA eager to control the “sea of black gold”.

Religion

Kia describes the different left groups both within and outside Iran (all detailed in an appendix). He also describes the plight of those who were forced to move from the countryside, with the White Revolution, to live in the cities. They crowded into sprawling shanty towns and just about made out by doing casual and temporary work. They were later used by the mullahs as their social “battering ram”. Something facilitated by the fact that, though the shah established a one-man dicatorship and crushed the organised left, he allowed the mosques to largely continue unaffected. True, there were violent clashes and some chose exile, most notably ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, but the mullahs maintained and grew their organisational nexus through their guiding hierarchies, student seminaries, congregations and financial deals with the bazaarees.

Taking up the mantel of the downtrodden and dispossessed, the mullahs posed as radicals. But in reality political Islam was a reactionary protest against the shah’s version of modernity and, in the absence of anything like an effective left, could place itself at the head what became first widespread popular discontent, then a mass protest movement and finally a fully fledged revolution.

The shah knew he stood atop of a social volcano that could erupt at any moment. From 1975, all young people were officially considered suspect. Savak (the shah’s secret police) would detain at random, torture those suspected of political opposition and force them to provide names of acquaintances, who were then treated in the same way. Occasionally, they might even pick up someone who was a leftist guerrilla, and in this way the shah could claim the country had become the “island of security” he had promised.

But revolt was always near the surface. Kia recalls the signs of dissent at the medical school where he was teaching. Over the following chapters we are told about the steeply rising tide of struggles and how the mullahs were prepared to compromise with the radicals on occasion in the attempt to gain control. Either way, guerrilla actions, workers’ strikes and protest demonstrations were met with severe repression: around 10,000 were killed in the 1970s and another 40,000 seriously injured.

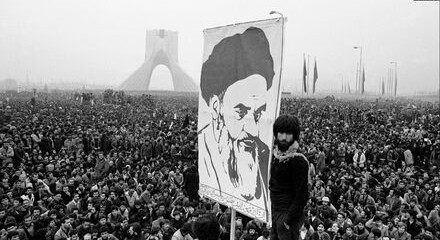

Of course, the shah was eventually forced to seek ‘medical treatment’ abroad - taking with him and his entourage whatever ill-gotten gains he could. Massive protests, involving hundreds of thousands, then millions taking to the streets, culminated in a nation-wide strike by oil workers and an armed uprising. Officers faced widespread insubordination and rank and file unwillingness to fire upon their own mothers and fathers, brothers and sisters. Leftist guerrillas broke into arsenals and handed-out weapons to the awaiting masses. However, the dominant ideas remained the ideas of the mosque. And with the blessing of the Americans, Khomeini was allowed to return from his Paris exile. Landing at Tehran airport on February 1 1979 he instantly became the leader of a revolution that quickly became a counterrevolution.

Kia describes the slide - including how things looked from the medical school and hospital where he worked in Shiraz. He recalls how the new Khomeini regime dispensed with liberal, then leftist allies and began to clamp down on the freedoms established with the fall of the shah in the name of sharia law. Feeling as though all his ideals were being trampled on, Kia sought an explanation.

Imam’s line

A group founded out of the coming together of various left factions had been established: Rahe Kargar, which he joined. But, he describes how the left in general made a fundamental mistake - they did not go back to the original Marxist texts, did not learn to think concretely, but instead went along with the Khomeinites, and various left Islamists, when they used the language of anti-imperialism. There was talk of the ‘Imam’s line’ and Iran being an ally of the Soviet Union and the ‘socialist bloc’. Most leftwingers, and not only Tudeh and the Fedayeen (majority), but the Fourth International’s co-thinkers, seemed to rely on a few simple formulae - not unlike religious dogma. In addition, he says, left groups mostly restricted their political reading to their own material, thereby drawing walls around themselves, so as not to have to come to grips with what were complex realities.

The result was clear. The new regime was not at all impressed by the left’s ‘conditional support’ and soon viciously turned on its supporters. Comrade Kia himself was arrested in 1981 and imprisoned for just over a year, when, fortunately, he was one of the 300 prisoners released when the now constitutionally-enshrined supreme leader, Ruhollah Khomeini, declared an amnesty.

He describes his own prison experiences, the bravery and the organisation of the prisoners, including their self-education, and the arbitrariness of the court system. Upon his release, he felt he had no choice but to leave Iran. The book closes with him flying into London: “I had grown up, rather late. But I had grown up …”

Throughout, Kia fluidly uses quotes from Farsi poetry, writers as different as Franz Fanon, Don DeLillo, Arthur Koestler, Peter Hoeg, Yevgenia Ginzburg, Roy Medvedev and Seamus Heaney to illustrate his thoughts. He wears his education lightly - but always to enlighten.

This is a book that is at the same time historical, educational, sad and engrossing. Even with 53 chapters, the combination of shortish sections and simple, friendly writing makes it easy to read - for me more than once (!) - thanks to all it teaches.

Anyone involved in such a struggle must learn and relearn over and over again: we must draw up a full analysis of that struggle - both its achievements and drawbacks, as well as the essential political lessons. As comrade Kia says, “You become part of the stream of history, part of the inevitable. There is no ‘I’ in revolution. Only necessity.”