27.11.2025

What a cop-out

You could not make it up, says Eddie Ford. Cop30 did not even mention coming off fossil fuels in its final text. Nor, despite being held in Belém, the gateway to the Amazon, was there a commitment to halting deforestation

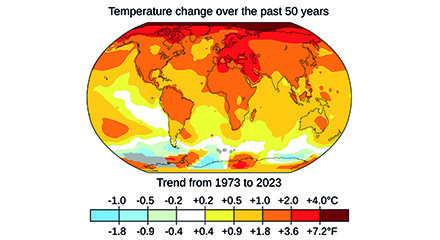

In the end, you could not make it up. The planet is getting warmer and warmer, with the last three years the hottest years on record and, as the latest research extensively documents, various tipping points are being reached - glaciers melting; forests disappearing; wildfires, floods and droughts increasing. With the Paris agreement pledge to keep global surface temperatures “well below” 2°C above pre-industrial levels completely dead, let alone keeping the increase to only 1.5°C, the world is steadily heading towards around 2.8°C.1

Yet the final text of Cop30 did not even mention coming off fossil fuels, as if relentless warming is not happening, because the petrostates grouped around Saudi Arabia fought off a coalition of 90 countries wanting a commitment to “phase out” fossil fuels. Rather, the text merely added a reference to the “UAE consensus” - ie, the overall package from Cop28 in Dubai in 2023 that contained the first pledge to transition away from fossil fuels. But it is important to remember that this so-called pledge was itself a wretched compromise, as countries like Russia, Saudi Arabia and China rejected the “phase out” formulation in favour of “phase down” - Cop28 adopting a last-minute resolution stating that the “transition away” was going to be done “in a just, orderly and equitable manner” to “mitigate” the worst effects of climate change, and net zero will be magically reached by 2050.

Coalition of willing

Now we are told that this “transition away” from fossil fuels will proceed “outside” the UN process and will be “merged” with a plan backed by Colombia and about 90 other countries, with a summit set for April 2026 where this “coalition of the willing” will supposedly push progress forward. André Corrêa do Lago, the Brazilian diplomat who was Cop30’s president, tried to reassure us that the plan to “develop” the roadmap had the support of president Lula da Silva and would involve “high-level dialogues” over the next year involving governments, industry and civil society. Once complete, according to do Lago, they would “report back” to Cop - which is obviously a recipe for endless dither and delay, but will be a great junket for the great and the good.

Similarly, though perhaps even more grotesque, was the blocking of any plans to include a roadmap about ending deforestation - even though Cop30 was deliberately sited in Belém precisely because it is known as the gateway to the Amazon: the Tropical Forest Forever Facility (TFFF) that was proposed by the Brazilian government was meant to be a “signature achievement” at the conference with the largest indigenous delegation of any previous Cop.2 Indeed, Cop30 was styled by the Lula government as the “Indigenous Cop” that for the first time was going to recognise native people’s land rights and knowledge as a fundamental climate solution.

But, of course, for all of the propaganda and PR of the Brazilian state, indigenous peoples were excluded from the negotiations, actually staging protests and demonstrations - especially against the building of a four-lane highway for the conference that cut over eight miles through the protected rainforest, and the Lulu government’s plans to open up oil wells in the mouth of the Amazon to finance the “transition away” from oil. In other words, just like the Tories wanting to drill in the North Sea for new oil fields because it ‘makes no real difference’ - which is essentially correct, of course, but, if everyone is going to “drill, baby, drill”, that can only accelerate the climate crisis.

But deforestation was killed off after being tied to the fossil fuels roadmap and the tying of the two could be interpretated as either a terrible diplomatic blunder or deliberate sabotage by the Brazilian foreign ministry, which has long had a focus on selling the country’s oil abroad - take your pick. So now, just like the fossil fuel roadmap, TFFF is going to happen “outside” Cop and the UN process, even though it is obvious, even to a completely uniformed observer, that dealing with the climate crisis and forest protection are closely connected.

Insult

At Belém, it was agreed to triple fund adaptation - that is, money will be provided by richer states to poorer countries, so that vulnerable countries can help protect themselves from the escalating impacts of the climate crisis. But the goal of possibly $120 billion a year was pushed back five years to 2035 from the initial suggested date of 2030 and many observers are angered by the refusal to commit to scaling up finance to the $300 billion annually deemed necessary - some calling it an “insult” for everyone facing flooding, fires and drought.

Predictably, the ‘Baku to Belém roadmap’ agreed last year at Cop29, whereby “all actors” would “work together” to enable the scaling up of financing to developing countries for climate action to at least $1.3 trillion per year by 2035, proved to be a damp squib - how this will be structured, administered and implemented was not fleshed out at Belém, leaving the roadmap hanging in mid-air.

Equally, the Loss and Damage Fund, first agreed at Cop27 in Sharm el-Sheikh in Egypt, remains chronically underfunded and vague - conceived originally as a multilateral mechanism to help countries deal with irreversible harms from climate change that cannot be addressed through mitigation or adaptation alone (eg, various forms of extreme weather damage).

In theory, this meant that the most vulnerable countries (particularly small-island states) can officially request grants - typically in the range of $5-20 million per project - for loss/damage projects, such as post-disaster rebuilding, infrastructure repair, ecosystem restoration or relocation support, etc, etc. But, as of this year, total pledges stand at under $800 million - tiny, when compared to the estimated annual global “loss and damage” costs, which could reach hundreds of billions of dollars per year for ‘at risk’ countries. Furthermore, aid agencies say that the allocated resources are “too restrictive and too slow to respond” to the scale and frequency of climate-driven disasters - meaning that the Loss and Damage Fund will essentially remain an empty shell without a huge scaling-up of the provision of public finance in grants.

Yet UN data scarily shows that levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere soared by a record amount last year to hit another high, and the global average concentration of the gas surged by 3.5 parts per million to 424ppm in 2024. According to the World Meteorological Organisation, this is the largest increase since modern measurements started in 1957, meaning that there will be more disasters created by climate change. Making matters worse, fewer than a third of the world’s states - 62 out of 197 - have sent in their climate action plans, known as Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) under the Paris agreement. As for the US, the country which is the largest emitter per person, it has abandoned the process altogether - it did not even send an official delegation to Belém, with Donald Trump calling human-induced climate change “the greatest con job ever perpetrated on the world”. Dismally, none of the 45 global climate indicators analysed are on track for 2030.

Methane

We must not fall into the trap of thinking that it is only carbon emissions that pose a danger. Criminally, the impacts of the food and agricultural system - such as cattle in cleared tracts in the Amazon - were largely ignored at Cop30. This is despite the fact that methane is a greenhouse gas 80 times more powerful than carbon dioxide, and is responsible for about a third of the warming recently recorded, so cutting it could amount to what some describe as an ‘emergency brake’ on global temperature rises. Hence, Cop26 in Glasgow had agreed to a cut in methane emissions of 30% by 2030. Yet they have actually continued to increase and, collectively, emissions from six - the US, Australia, Kuwait, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and Iraq - are now 8.5% above the 2020 level, which is deeply worrying.

Maybe in an ominous indication of the future, a fire near the delegation offices forced evacuation of the conference centre and disrupted negotiations at a crucial stage, as the Brazilian presidency of Cop30 put together a final package termed the “global mutirão”.3 With a name meaning “collective efforts”, it attempted to draw together the issues that had divided the fortnight of talks, including finance, trade policies and the failure to meet the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C temperature goal.

Communists, of course, had rather low expectations regarding Cop30, but it failed to meet even the low standards normally seen in Cop meetings - representing a triumph of narrow self-interest over the common good. Even if liberal opinion comforts itself with the illusion that some progress was made at Belém, exemplified by the headline in The Guardian: “End of fossil fuel era inches closer, as Cop30 deal agreed after bitter standoff”.4 There are no fools like liberal fools.

Profits

At the moment we are at peak coal.5 The reasonable expectation is that it will start to go down from now onwards, but, on the other hand, oil - and presumably gas - is expected to go up and up. True, more and more power is being accounted for by renewables, mainly solar with a bit of wind - and in the official statistics, of course, that also includes nuclear, which is perversely classified as a ‘renewable’, when it is nothing of the sort.

But the fact that renewables account for a bigger percentage does not detract from the reality of more and more energy being used - especially as we have to take into account the important factor, which is sometimes overlooked, that governments and companies throughout the world are heavily investing in AI, which uses massive amounts of electricity. So while you have got renewables and they are becoming steadily cheaper - as this publication has often pointed out - the operating profit on them is very low, as opposed to oil and gas, which is very high.

So it is not the price of renewables versus fossil fuel that is the obstacle to meeting the investment targets to limit global warming: rather it is the profitability of renewables, compared to fossil fuel production. Therefore we have the example of Sweden, where wind power can be produced very cheaply, but the very cheapening of the costs also depresses revenue potential. This fundamental contradiction explains the arguments from fossil fuel companies that oil and gas production cannot be phased out quickly, which is perfectly logical from their point of view. Indeed, the very fact that the profitability of oil and gas has generally been far higher than that of renewables explains why in the 1980s and 1990s the oil and gas majors unceremoniously shuttered their first ventures in renewables almost as soon as they had launched them.

Naturally, it is still the case that investment in renewable energy currently offers sub-par returns, as in a recent assessment by JP Morgan economists - so stick to fossil fuels, no matter what the ecological impact is, because the holy mission is to protect the bottom line.