20.11.2025

Capital’s structural rot

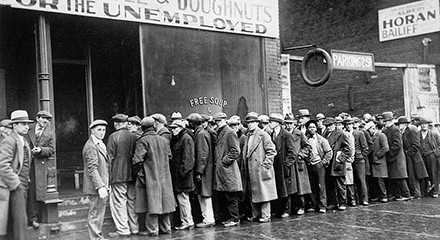

As stock markets reach new highs in a speculative orgy, perhaps the signs are that a massive crash, outdoing 1929, is already underway. The stats for the jobs market, private and government borrowing and housing certainly show that America, the world’s largest economy, is entering recessionary territory. World socialism becomes ever more necessary, writes Ted Reese

The latest - possibly greatest ever - global capitalist meltdown is underway. US unemployment has been ticking upwards for the past two years and, after the worst October for 22 years, job losses have already hit 1.1 million in 2025 - up by 65% year-on-year.

Job cuts have surpassed one million in a single year only four other times in the past 32 years: in 2001 when the dot-com bubble burst; 2008 and 2009, during the housing market crash and Great Financial Crisis (GFC); and in 2020, when the Covid pandemic and lockdowns struck (following flatlining growth in 2019). The federal government leads the way with 300,000 job losses, followed by the technology sector (100,000), warehousing, retail and services.

According to Moody’s Analytics, 22 US states and the District of Columbia have experienced shrinking gross domestic product this year, and another 13 have flatlined, leaving only 16 generating or experiencing growth.

A wide range of economic data signals a brewing crisis. The Institute for Supply Management manufacturing index indicated a contraction in the US manufacturing sector for seven consecutive months up to the end of September, putting the index at 49.1 - a figure strongly associated with economy-wide recession.

Housing starts in the US are expected to come in at 1.3 million this year, having dropped from 1.6 million in 2021 to 1.55 in 2022, 1.42 in 2023, and 1.36 in 2024. In August, the delinquency rate of office mortgages packaged into commercial, mortgage-backed securities jumped to 11.7%, surpassing the 2008 peak of 10.7%. As recently as December 2022, the rate stood at only 1.6%.

Some 67% of Americans are living paycheck to paycheck (up from 63% in 2024, according to PNC Bank) - spending their entire income on bills and expenses and leaving little or no money for savings or emergencies.

Desperate not to spook investors, multinational investment bank Goldman Sachs contended in October that “anticipated investment returns are sustainable”. In the past three years the value of the stock market index, S&P 500, has doubled - putting it at 179% of GDP - something that took 20 years from 1965-85; or 17 in 1997-2014. The wider Wilshere 5000 is at a record high of 223% of GDP, beating the 193% of December 2021 and 135% of March 2000. A stock market frenzy, however, is itself a bellwether of a weakening real economy, since a shortage of profitable opportunities in commodity production - where new value is created - is chucked instead into the glorified betting of speculation, inflating the value of stocks and generating a false sense of prosperity.

Many commentators and analysts sounding the alarm are drawing comparisons to 2008 and 1929. The situation might well be worse than either. At the end of 2024, US banks had about $483 billion of unrealised losses on their securities; compared to no more than $150 billion in the run-up to the GFC.

The concentration of stocks and general wealth in the US is now on a par with the late 1920s, for the first time since that dark period. The population’s richest 10% of households own 94% of the stock market’s value. The top 25 stocks account for 45% of the S&P 500 and the top seven for 31%. Nvidia’s market cap is 7% of all 3,265 publicly-traded US companies.

But only 10% of households had invested in the stock market when it crashed in 1929 - now 62% of American adults report owning stocks (and that is not counting retirement funds that are often directly or indirectly invested in the stock market). At least 43% of retail investors (individuals) are buying more stock than their cash can afford. America’s economy is the stock market and, at an all-time high, it is highly leveraged.

In the run-up to the Great Depression (1929-39), active home mortgages represented 10% of America’s GDP, rising to 32% in 1930. American mortgage debt today is 70% of GDP, more than $18 trillion in total household debt. (In Australia and Canada, mortgage debt is higher than the country’s entire GDP.)

The rapid expansion of margin debt - the total amount that investors have borrowed to buy securities, which fuelled the 1929 crisis - reached a record high of $1.1 trillion in September (up by 34% on 2024). The private (non-bank) credit market is exploding at a rate of around 15% a year, rising from $0.5 trillion back in 2012. Drawing comparisons to the 2008 subprime housing crisis, US subprime used-car lender Tricolor filed for bankruptcy in September after it allegedly pledged the same loan portfolios to multiple lenders, exposing private credit providers and major banks, such as JPMorgan, Barclays and Fifth Third, to unexpected losses, with its filing listing up to $10 billion in assets and liabilities.

Everything bubble

The private credit bubble is only one part of a much larger one - an ‘everything bubble’ that since the GFC has for the first time ever engulfed every asset class. Now the ‘AI bubble’ has joined the party and out-bloated all that came before. The top ‘Magnificent 7’ stocks are all tech-sector, and the tech and artificial intelligence sector accounts for a whopping 50% of the US’s GDP growth this year (92% in New York, California and Washington). Since the debut of the advanced research assistant tool, ChatGPT, in November 2022, AI-related stocks have added an estimated $17.5 trillion in market value - 75% of the S&P 500’s gains.

In breakneck competition to construct expansive data centres, equipped with specialised, cutting-edge chips, Microsoft, Alphabet, Amazon and Meta reported a combined capital expenditure of $245 billion in 2024 - a figure expected to surpass $360 billion this year. According to an MIT report, though, only 5% of integrated AI tools are generating profitable returns.

In the third quarter, venture capital deals with private AI firms dropped by 22% quarter-on-quarter. Amid ongoing problems with reliability and the rocketing costs of training new models, furthermore, AI-tool usage at firms with more than 250 employees dropped from nearly 14% in June to under 12% in August. According to Edge AI & Vision Alliance, training costs have surged by more than 4,300% since 2020, driven mostly by the rising price of chips and staff (engineers and researchers).

Investment has been pouring into AI stocks out of lack of other options. Oracle’s debt-to-equity ratio is a scarcely believable 500%. Chat-GPT owner OpenAI is valued at $500 billion, but lost $4.3 billion in the first half of 2025 and is expected to lose $14 billion in 2026. The company does not expect to be profitable until the end of the decade and is now begging tail-between-legs for a government bailout, potentially heaping yet more debt onto the back of a public increasingly weighed down by the burden of saving the private sector continuously since 2008.

According to MacroStrategy Partnership, the sheer volume of capital flowing into AI dwarfs previous speculative orgies, estimating a “misallocation of capital” equivalent to 65% of US GDP - four times more than the housing bubble and 17 times more than the dot-com bust.

Nvidia, OpenAI and major data centre operators are propping up one another’s growth through large, incestuous circular investments. As demand far outstrips supply, Nvidia sells its chips (which it designs, but are actually manufactured by Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company) at an extremely high margin. It is left with little choice but to subsidise that demand by investing in AI firms that then purchase its hardware. OpenAI has committed to buying 10 gigawatts of compute from Nvidia, at a cost at least $15 billion each; but in return Nvidia is investing $100 billion in OpenAI (for non-voting shares). Similar arrangements run through other firms like CoreWeave and Nebius.

As profitability falls, liquidity reserves and lending dry up and job losses rise; the Federal Reserve, the US central bank, is tentatively lowering its baseline interest rate to encourage banks to transfer their reserves onto the market (at higher rates) - fuelling the bubble.

If an ‘external’ factor does not spook investors first, the intensifying concentration of stocks will eventually shut out too many of them from returns and a massive sell-off will begin, bursting the bubble. The fictitious ‘money’ which investors have been throwing into this hole will be wiped off the ledger board. A 30% correction is strongly correlated with an economy-wide recession.

Gita Gopinath, former chief economist of the International Monetary Fund and now with Harvard, believes that a market correction of the same magnitude as the dot-com crash - when the S&P 500 and the NASDAQ Composite crashed by 50% and 75% respectively - could wipe out about $20 trillion in wealth for American households (nearly 70% of annual US GDP). On that basis, consumption would fall by more than three percent and GDP by two percentage points - easily enough to push the US economy into a deep recession. She also estimates that foreign investors could face wealth losses exceeding $15 trillion - about 20% of the rest of the world’s annual GDP, since US equities make up 60% of the global market. We should not be surprised if Gopinath’s estimate turns out to be wildly conservative.

1929 again

In contrast with the asset inflation that characterised the aftermath of 2009 and the asset and consumer price inflation after 2020, 1929 resulted in absolute overall deflation, which the Fed is desperate to avoid, since money loses its value faster relative to debt, and demand falls faster in anticipation of falling prices. The Wall Street crash impacted the whole world so badly, because the US (then a net lender) was the world’s biggest lender. The rest of the world needed to borrow American capital to grow their economies.

As the home of the world’s dominant reserve currency and richest consumer base, a US collapse today will again, of course, shock the whole world. Now, though, the US is a net borrower and the largest borrower in the world. About 25% of its government spending is financed by foreign capital inflow, but the appeal of the devaluing US dollar appears to be waning. At the end of 2024, China’s US Treasury holdings were $759 billion, down from $1.07 trillion four years earlier. The figure for Japan is down from $1.3 trillion to $1.1 trillion. As a share of global reserves, the greenback has fallen to 56% from 73% in 2000.

Since 2020, official US government debt-to-GDP has been higher than the 119% at the end of World War II. On course to soon hit $40 trillion, US government debt is growing at around 6% per year and the annual government deficit (since 2008) 8.5%. As the debt rises, the risk of lending to the government climbs, as the chances of the overstretched tax base losing its capacity to repay (and with interest) therefore naturally increases. Lenders therefore tend to demand higher rates, further undermining their own investment, as the government is forced to increase its borrowing to cover the difference, expanding the money supply and fuelling inflation.

Interest payments grew from 6% of government spending in 2020 to 13% in 2024, making it the fastest growing component of government spending - and already surpassing the outlay on defence and medicare. This state of affairs is clearly unsustainable. The tax base, which capital is so dependent on for bailouts and subsidies, is collapsing.

The Trump administration is naturally desperate to bring borrowing rates down and is making moves to pack the Fed with its own people, in order to get its wish sooner rather than later. When the Fed lowers its interest rates, market rates usually follow to some extent, even if the Fed’s rate falls lower absolutely. In recent years, however, market rates have spiked in response to a lower Fed rate, in anticipation of higher government debt and inflation, making debt more expensive to repay, while relatively disincentivising borrowing, investment and dealmaking (mergers and acquisitions).

With inflation still stuck at 3% - above the 2% target aimed at maintaining business stability - the Fed is today much more reluctant to intervene than in the past. US inflation hit a 40-year high of 9% in 2022, impacting not only assets, as in the aftermath of 2009, but also, this time, consumer prices. The average basket of goods is now 25% higher than in 2020.

As the economy deteriorates further, the Fed will have little choice but to once again drop its rate down to zero - as it did for the first time ever in 2009, and then in 2020 - and print money to buy debt from banks and corporations at an even greater rate than it did in 2008 and 2020, when the money supply grew by a shocking 40% in less than two years. The Fed’s coming intervention will again devalue wages and savings, amounting to another - likely greater - round of inflation. Countering inflation will, compared to the past, require limiting bailouts to a smaller proportion of the private sector and making even greater cuts in public spending.

Liberals and social democrats will blame Donald Trump’s anti-migrant policies for exacerbating labour shortages, along with his tariffs - taxes on American importers and consumers, which are impacting demand and draining reserves, but which are designed in part to tackle a government deficit that has been mounting over several decades.

Trump and his policies are symptomatic of deeper structural rot. The reality is that capitalism unavoidably generates the conditions of its own downfall. In summary, making profit, of course, requires growth (of commodity production) which, via innovation that speeds up production, tends to result in the devaluation of commodities and less profit per commodity. Capital is therefore increasingly dependent on making the state its biggest customer and bleeding the public dry.

Karl Marx

As the general rate of profit falls, investment opportunities dry up, resulting in ‘over-accumulated’ gluts of surplus money capital that cannot be profitably reinvested. Karl Marx’s contention that this immanent barrier to innovation and productivity growth tends to grow “more formidable” is illustrated in many ways: by the record high prices of cryptocurrency, gold and speculative stocks, for example; and the amount of dead cash amassing in US money market funds - hitting $7.5 trillion in 2025, up from $5 trillion in just three years.

Via bankruptcies, mergers and acquisitions - the recent deals between the likes of Nvidia and Open AI represent a gigantic proto-merger - the ownership of capital and wealth necessarily concentrates in order to offset falling profitability; excluding an increasingly large proportion of the population from the capitalist class, which is therefore pushed back into a corner of its own making, from where it lashes out increasingly aggressively, stimulating an intensifying class struggle, through which the working class must eventually prevail.

As capitalists continue to automate production in the effort to lower costs and rewiden profit margins, the contradiction at the heart of the system continues to deepen. No wonder AI is unprofitable - data is produced and rearranged at increasingly breath-taking speed. Unlike humans, robots and computers cannot be exploited through wage labour or by commodities capitalists need to sell. The fully automated system of production capital itself reaches for is making capitalism historically obsolete and (global) socialism necessary.

Why socialism? Empirical economic data again makes the case: that the concentration of wealth through bankruptcies and mergers is demonstrated by the fact that - despite 50 years of aggressive privatisation - the number of private banks and corporations in the US has roughly halved since the turn of the century. A ‘final merger’ evidently beckons - to be enacted by a socialist state, since a capitalist state cannot by definition expropriate the whole private economy - necessitating the transition to an economy owned entirely by the public, since no exchange of ownership is necessary in a total monopoly.

A long, hard, painful struggle awaits - but so too, at last, does working class liberation.