04.09.2025

The road from Eton College

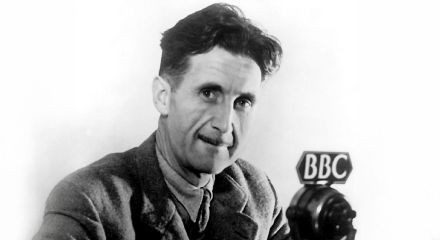

Seventy-five years after Orwell’s death, Paul Flewers continues his series by turning to his take on socialism, totalitarianism and the significance of Spain’s Civil War

The road from Eton College

Seventy-five years after Orwell’s death, Paul Flewers continues his series by turning to his take on socialism, totalitarianism and the significance of Spain’s Civil War

George Orwell travelled to Spain in December 1936 to fight in the Spanish Civil War. His experiences there proved to be extremely influential in two ways. Firstly, for the first time in his life, he saw the working class in a militant and confident mood. Secondly, he saw the murderous reality of the Stalinists, as they sought to destroy a revolution and crush all those who opposed them. The first factor was to fade in his consciousness until his confidence in the ability of the working class to shape its own destiny was little more than a memory and a hope for the future; the second was to remain a prominent and permanent influence upon his political outlook.

Many years later, Orwell stated that prior to 1936 he did not have “an accurate political orientation”. However: “The Spanish war and other events in 1936-37 turned the scale and thereafter I knew where I stood. Every line of serious work that I have written since 1936 has been written, directly or indirectly, against totalitarianism and for democratic socialism, as I understand it.”1

Arriving in Barcelona in December 1936, he found himself in a city in which, as he put it, “the working class was in the saddle”. Although he was a bit disconcerted by this unfamiliar phenomenon, he was to look back at it with fondness:

Above all, there was a belief in the revolution and the future, a feeling of having suddenly emerged into an era of equality and freedom. Human beings were trying to behave as human beings and not as cogs in the capitalist machine … There is a sense in which it would be true to say that one was experiencing a foretaste of socialism, by which I mean that the prevailing mental atmosphere was that of socialism. Many of the normal motives of civilised life - snobbishness, money-grubbing, fear of the boss, etc - had simply ceased to exist.2

Orwell went to Spain in order, as he put it, to fight against fascism and to fight for “common decency”.3 And if his belief in socialism was reinforced, as he discovered this quality amongst the Spanish workers, so was his dislike of Stalinism.

Franco’s military coup in June 1936 against Manuel Azaña’s liberal coalition administration provoked a militant response. Workers and peasants seized factories and the land, which they then controlled through elected committees. They set up militias to fight Franco’s troops. Although the political centre ground between the militant upsurge and Franco’s forces was rapidly narrowing, the Communist International posed the struggle in Spain as one between “the proletariat, the peasantry, the democratic bourgeoisie and the intellectuals on the one side, and the monarcho-feudalist reactionaries, the counterrevolutionary fascists, on the other”. The fight was “for the maintenance of the democratic republic”, not for socialism.4

This was not an academic matter, a case of fraternal debate. A civil war was soon to break out within the republican side, with the marginalised republican government being propped up by the local Stalinists and by Soviet military and intelligence personnel. The latter imposed a reign of terror, with their secret police acting autonomously of any domestic control, and infiltrating the republican police and judiciary. Their main targets were their leftwing rivals.5

Orwell was at first more inclined towards the stance of the Communist International, that the war against Franco should be won before wide-ranging social reforms could be implemented, but he soon realised that this was unrealistic, as those who had first taken up arms against Franco combined that fight with the seizure and running of factories, transport and land; indeed “their resistance was accompanied by - one might almost say it consisted of - a definite revolutionary outbreak”. He came to recognise that the Stalinists’ policies were not only holding back and even reversing the struggle for social gains, but were demoralising the militants, and impeding the war effort against Franco.6

Stalinism

He reacted strongly to the slanderous campaign conducted by the Stalinists against other leftists, and he attempted to help those who had been imprisoned. He trod on many sensitive toes with his trenchant writings:

When I left Barcelona in late June [1937] the jails were bulging … But the point to notice is that the people who are in prison now are not the fascists, but revolutionaries; they are not there because their opinions are too much to the right, but because they are too much to the left. And the people responsible for putting them there are … the communists.7

Orwell was very disturbed that his writings were censored and rejected by such publications as the News Chronicle and the New Statesman, which preferred to believe the official communist version of events in Spain.8

After his return from Spain, Orwell spent a lot of time grappling with the questions of socialism, Stalinism, democracy and totalitarianism. Unlike many leftwingers, he saw through the barrage of Stalinist propaganda. His parody of the Moscow trials remains a delight:

Mr Winston Churchill, now in exile in Portugal, is plotting to overthrow the British empire and establish communism in England. By the use of unlimited Russian money he has succeeded in building up a huge Churchillite organisation, which includes members of parliament, factory managers, Roman Catholic bishops and practically the whole of the Primrose League … Eighty percent of the Beefeaters at the Tower are discovered to be agents of the Comintern … Lord Nuffield … confesses that ever since 1920 he has been fomenting strikes in his own factories. Casual half paras in every issue of the newspapers announce that 50 more Churchillite sheep-stealers have been shot in Westmoreland or that the proprietress of a village shop in the Cotswolds has been transported to Australia for sucking the bull’s eyes and putting them back in the bottle.9

Nevertheless, unlike many anti-Stalinist leftwingers, in particular the Trotskyists, he did not take a positive view of Bolshevism. One of his major criticisms of not merely Stalinism, but of the whole Bolshevik tradition, was that it restricted democracy. He insisted that socialism had to be democratic, and he rooted the rise of totalitarianism in the Soviet Union in what he saw as the Bolsheviks’ rejection of democracy: “The essential act is the rejection of democracy - that is, of the underlying values of democracy; once you have decided upon that, Stalin - or at any rate someone like Stalin - is already on the way.”

Orwell rejected Trotsky’s criticisms of Stalinism, stating that he could not avoid taking responsibility for the evolution of the Soviet regime, and there was no certainty that “as a dictator” he would have been preferable to Stalin.10 He wondered if the Soviet Union constituted “a peculiarly vicious form of state capitalism”, and made a significant comparison, when he stated that the society described “does not seem to be very different from fascism”.11

Orwell was convinced that the whole thrust of societal development was towards totalitarianism. At this juncture, he claimed that the government’s preparations for the forthcoming world war would lead to the establishment of “an authoritarian regime” along the lines of “Austro-fascism”.12 Although he used language reminiscent of the far left, when he condemned the Communist International and its Popular Front campaign - the call for all social classes to demand an Anglo-Franco-Soviet ‘collective security’ alliance against Germany for mobilising support for a world war13 - his anti-war stance of the late 1930s was predicated upon his concept of the totalitarianisation of society, rather than, as in the case of anarchists and Trotskyists, upon an overall rejection of participation in an imperialist war.

Orwell’s feelings, as war approached, can be ascertained, if rather obliquely, in his novel Coming up for air, which he wrote in early 1939. It brings out in a necessarily refracted form many of his concerns about the future, and many of the themes that are introduced play a major role in his subsequent works, both fiction and non-fiction, and underlie much of his thinking at the start of World War II.

The main character in Coming up for air is George Bowling, a middle-aged, middle-class insurance salesman who returns to Lower Binfield, his rural Oxfordshire birthplace, for the first time in over two decades. Bowling’s lengthy reminiscences of his childhood and youth serve to reinforce the core of Orwell’s thinking, that people thought that something good in society - a feeling of security or, more exactly, a feeling of continuity - was disappearing, and would not, indeed could not, be regained. Furthermore, if in the past “it was simply that they didn’t think of the future as something to be terrified of”, now the future is an enforced uniformity with everything “slick and shiny and streamlined”, “celluloid, rubber, chromium steel everywhere, arc-lamps blazing all night, glass roofs over your head, radios all playing the same tune, no vegetation left, everything cemented over”. The futuristic glass and concrete factories of The road to Wigan Pier make a reappearance.

Bad times

The rapidly approaching war hangs like a shroud over Coming up for air, but the war itself is not really the problem; it is the “after-war” that is really frightening. For all the talk of uncertainty in the future, there is a very real certainty: “The bad times are coming …” Images of a future repressive, regulated - in other words, totalitarian - society occur and reoccur throughout the book. ‘Rubber truncheons’ - not any old truncheons, but rubber ones - crop up with monotonous regularity, and barbed wire, slogans, posters with “enormous faces” and street tannoys announcing the latest victory make their appearance: a series of ugly interruptions to the dreamy reminiscences, a premonition of the dystopia of 1984.14

Despite the vividness and sharpness of his overtly political writings, these glimpses in this novel of a post-war nightmare are perhaps the most illuminating insights into Orwell’s fears, as the world tipped into the biggest and most destructive war in history.

-

G Orwell ‘Why I write’, Collected essays, journalism and letters (CEJL) Volume 1, Harmondsworth 1984, pp26, 28.↩︎

-

G Orwell Homage to Catalonia Harmondsworth 1989, pp2-3, 82-83.↩︎

-

Ibid p188.↩︎

-

International Press Correspondence August 8 1936.↩︎

-

Two attempts by Bill Alexander and Robert Stradling, both partisans of the ‘official’ communist movement, to discredit Orwell’s Spanish accounts concentrated on minor points of dispute with him, and said little (Stradling) or nothing (Alexander) in respect of his statements about Stalinist atrocities in Spain. See B Alexander, ‘George Orwell and Spain’ and R Stradling, ‘Orwell and the Spanish Civil War’ - both in C Norris (ed) Inside the myth: Orwell: views from the left London 1984.↩︎

-

G Orwell Homage to Catalonia Harmondsworth 1989, pp90, 190.↩︎

-

New English Weekly July 29 1937. Orwell was never forgiven by the official communist movement for exposing its baleful role during the Spanish Civil War. Indeed, such was its enduring loathing of him that he even achieved the seemingly impossible feat of uniting the warring factions of the CPGB, whilst it was tearing itself apart in the mid-1980s: grizzled, old-style ‘tankies’, nostalgic for the glory days of Stalin, joined forces with the sleek young Eurocommunists in a book-length attack upon the man and all his works: ie, Norris’s Inside the myth (see note 5).↩︎

-

. G Orwell ‘Letter to Frank Jellinek’ CEJL Volume 1, p403.↩︎

-

. New English Weekly June 9 1938.↩︎

-

. New English Weekly January 12 1939. Later on, he stated that something like the purges was implicit in Bolshevik rule: “I could feel it in their literature” (G Orwell ‘Wartime diary: 1940’ CEJL Volume 2, p393). Similarly, when reviewing a book by Arthur Koestler, he considered that the author’s criticisms of the Soviet Union were “vitiated by a lingering loyalty to his old party and by a resulting tendency to make all bad developments date from the rise of Stalin: whereas one ought, I believe, to admit that all the seeds of evil were there from the start and that things would not have been substantially different if Lenin or Trotsky had remained in control” (G Orwell, ‘Catastrophic gradualism’ CEJL Volume 4, p35; Koestler was merely referring to the Trotskyist view, not endorsing it (A Koestler The yogi and the commissar London 1945, pp127-35.↩︎

-

. New English Weekly June 9 1938. The idea that the Soviet Union was a state-capitalist society was popular across the political spectrum during this period: see my The new civilisation? Understanding Stalin’s Soviet Union 1929-1941 London 2008, pp131-38, 184-200.↩︎

-

. G Orwell ‘Letter to Herbert Read’ CEJL Volume 1, p425. Many leftwingers in Britain thought that civil liberties would be severely restricted when war broke out. One Trotskyist group sent its leadership to the Republic of Ireland: see S Bornstein and A Richardson War and the International: a history of the Trotskyist movement in Britain 1937-1949 London 1986, pp8-11.↩︎

-

. G Orwell ‘Letter to Geoffrey Gorer’ CEJL Volume 1, p317.↩︎

-

. G Orwell Coming up for air Harmondsworth 1963, pp25-27, 106, 165, 225.↩︎