28.08.2025

The road from Eton College

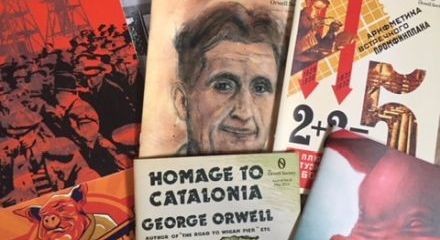

Seventy-five years after his death and eighty years after the first publication of Animal farm, Paul Flewers introduces his seven-part exploration of George Orwell’s life, works and politics

“Have you read this book? You must read it, sir. Then you will know why we must drop the atom bomb on the Bolshies!” With these words, a blind, miserable news-vendor recommended to me 1984 in New York, a few weeks before Orwell’s death. Poor Orwell, could he ever imagine that his own book would become so prominent an item in the programme of Hateweek?1

George Orwell was a radical socialist until he died. Yet his last two novels, Animal farm and 1984, are far more famous for having been used as cold war propaganda. Isaac Deutscher’s tale is a poignant example of this. In the decades since his death in 1950, Orwell has suffered the indignity of being probably the only unrepentant radical socialist who has been championed by large numbers of conservative and liberal thinkers, and whose works have been regularly used to oppose the very ideas he fought for until his death.2 This extended essay aims to explain this paradox.

Like many who went through the British educational system in the 1960s and early 1970s, I read both Animal farm and 1984 as part of an O Level syllabus. Although Orwell was described as a socialist, the books were interpreted in an anti-socialist manner, that any attempt to introduce socialism would lead inexorably to ‘Big Brother’ and brutal interrogations in the ‘Ministry of Love’. Only when I became a socialist in the late 1970s did I start to learn the truth about Orwell.

This is the first instalment of a seven-part Marxist analysis of Orwell’s politics. This opening part investigates Orwell’s conception of socialism, as it formed in the 1930s, and the basis of his hostility towards Stalinism. The second part shows how these two factors were developed by his experiences in the Spanish Civil War. The third part looks at the way in which he attempted to develop a strategy for socialism that could prevent a drift into totalitarianism.

The fourth and fifth parts investigate Orwell’s Animal farm and 1984, showing how the novels have been interpreted, and explaining how they could be used as anti-socialist propaganda. The sixth appraises Orwell’s conception of totalitarianism, and asks how well it has endured, particularly in the light of the collapse of the Soviet bloc. The seventh part looks at the revelations about Orwell’s links with the foreign office’s Information Research Department (the anti-communist propaganda organisation set up by Clement Attlee’s Labour government in 1948), and relates this to his overall political approach.

Anti-Stalinism

Although Orwell’s experiences as an imperial policeman in Burma were to propel him towards radicalism and a lifelong antipathy towards the power of the state over individuals, his first overtly political work was The road to Wigan Pier. Published in 1937, the first part of the book is a series of vignettes of the industrial north of England. The second part is a credo of Orwellian socialism, and there are clear indications of his feelings and fears that would assume a full-blown dimension in Animal farm and 1984.

The book outraged many, including its publisher, Victor Gollancz, by its scathing attack on the socialist movement in Britain. Amidst the well-known epithets - “nancy poets”, “vegetarians with wilting beards”, “earnest ladies in sandals”, “every fruit-juice drinker, nudist, sandal-wearer, sex-maniac, Quaker, ‘Nature Cure’ quack, pacifist and feminist in England”, to mention just a few - Orwell aimed a few barbs at the official communist movement, pointing to “Bolshevik commissars (half-gangster, half-gramophone)” and “shock-headed Marxists chewing polysyllables”. For him, socialism in Britain no longer smelled of “revolution and the overthrow of tyrants”: it reeked of “machine-worship, and the stupid cult of Russia”.3 Orwell’s full-blooded antipathy to Stalinism - something that was most unusual during the late 1930s, when even many anti-socialist commentators had something appreciative to say about the Soviet Union - is clear.4

Orwell’s hostility to Stalinism was based upon three factors. Firstly, he held all forms of socialist theory in contempt, and dismissed Marxism, stating that the left could not afford to be “a league of dialectical materialists”. He showed little patience with the “doctrinaire priggishness” and “party squabbles” of the left. This was aimed at the Marxian left, with its penchant for polemics and theoretical constructs, of which the Communist Party of Great Britain was by far the largest component.5

Secondly, his description of “Bolshevik commissars” as “half-gangster, half-gramophone” was based upon his experience of those in and around the CPGB, but can also be seen as a criticism of the regime in the Soviet Union. Orwell read widely, and was acquainted with a wide range of critical writings on the USSR. He reviewed three informative books in the late 1930s on the Soviet Union and the official communist movement: namely Assignment in utopia by Eugene Lyons, a disillusioned American fellow-traveller; The Communist International by Franz Borkenau, a former member of the German Communist Party, who was to become a friend and an influence upon him; and Russia under Soviet rule by Nicholas de Basily, a well-informed Russian exile.6 He had also read Ante Ciliga’s The Russian enigma,7 and Max Eastman’s The end of socialism in Russia,8 and owned a sizeable collection of far-left pamphlets.9 He was also in contact with a wide range of leftwing individuals, and, as anyone active on the leftwing scene will readily understand, he would have come across people’s ideas - interpreted, to varying degrees of accuracy, by a third party - even if he had not actually read any of their writings.

Industrial growth

Thirdly, he disliked the hailing of Soviet industrial growth. This was a part of his general suspicion of industrialisation. Orwell condemned the technocratic concept that ‘progress’ was essentially the emancipation of humanity through the development of technology and industry. He recoiled at the vision of the “huge glittering factories of glass and concrete” of the future. He recognised that the machine age was here to stay, but he was deeply uneasy about it. Industrialisation was leading inexorably to “some form of collectivism”, but it need not be of a socialist form:

… it is quite easy to imagine a world society, economically collectivist - that is, with the profit principle eliminated - but with all political, military and educational power in the hands of a small caste of rulers and their bravos. That or something like it is the objective of fascism. And that, of course, is the slave state, or rather the slave world … It is against this beastly possibility that we have got to combine.10

The development of industry would be a major factor behind the rise of a collectivist ruling élite, running an étatised society without a profit motive. Orwell was worried that, if the socialist movement could not win over the middle classes, they might be attracted towards such a society.11

Ethical

Orwell’s conception of socialism was essentially ethical, and he summed it up in the words, “justice and liberty”. Central to it was the call for decency in one’s political activities, and he subsequently harshly condemned leftwingers who wrote off “common decency” as mere “bourgeois morality”.12 Orwell’s socialism was, as Warren Wagar stated (citing Julian Symons), “of the heart rather than the slide-rule”, and Wagar made the accurate observation that Orwell was amongst the socialists who were “drawn to the cause by compassion or guilt or nostalgia for simpler ages, rather than by hard-boiled socio-economic analysis and theory”.13 Orwell’s biographer, Bernard Crick, added that he “demanded publicly that his own side should live up to their principles, both in their lives and in their policies, should respect the liberty of others, and tell the truth” - a stance which he considered to be “remarkable”.14

Orwell called upon leftwingers to unite and build a socialist party as “a league of the oppressed against the oppressors”. Here, however, he ran into a problem that was to dog him throughout his career as a socialist. Claiming that workers were predominantly concerned with the bread-and-butter issues of the day, and were not interested in socialist theory (indeed, he stated that “no genuine working man grasps the deeper implications of socialism”), he implied that workers who did educate themselves would automatically be corrupted by becoming union or Labour Party officials, or by squirming their way into the literary intelligentsia and the radical middle class - the very people whom Orwell considered were predominant in the socialist movement, and whom he deeply distrusted.15

If, however, the socialist movement was “invaded by better brains and more common decency”, then he felt that the “objectionable types” would no longer dominate it. So if the untheoretical workers could provide the “common decency”, who would provide the “better brains”? It could not be the workers, because they would most likely be corrupted if they did educate themselves. Although he assumed that the leadership of any revolt would tend to be from the middle class, he considered that socialists from a bourgeois background at bottom still despised the class that they claimed to champion.16

Orwell was effectively tying a Gordian knot, and it was one which he was never able to disentangle or cut.

-

I Deutscher ‘1984: the mysticism of cruelty’ Heretics and renegades London 1955, p50.↩︎

-

The latest in this lengthy parade is Masha Karp’s George Orwell and Russia (London 2023); see my ‘Review essay’, George Orwell studies, 9:2, 2025: orwellsociety.com/feast-of-orwellian-writing-to-dip-into.↩︎

-

G Orwell The road to Wigan Pier (Harmondsworth 1983), pp30-31, 152, 160, 189-90. Orwell also took aim at those strong admirers of Stalin’s Soviet Union, Sidney and Beatrice Webb and George Bernard Shaw, with their idea of socialism as “a set of reforms which ‘we’, the clever ones, are going to impose upon ‘them’, the Lower Orders” (The road to Wigan Pier p157).↩︎

-

The industrial growth under the five-year plans and the introduction of extensive welfare and educational measures were praised by many western academics, politicians and journalists who firmly rejected the repressive aspects of the Soviet regime. See my The new civilisation? Understanding Stalin’s Soviet Union, 1929-1941 London 2008.↩︎

-

G Orwell The road to Wigan Pier pp89, 195. The CPGB’s membership rose steadily in the late 1930s, from 6,500 in 1935 to 17,750 in 1939: see N Branson History of the Communist Party of Great Britain, 1927-1941 (London, 1985) p188. This was many times the total membership of non-Stalinist Marxian groups in Britain.↩︎

-

E Lyons Assignment in utopia London 1938; N de Basily Russia under Soviet rule: 20 years of Bolshevik experiment London 1938; F Borkenau World communism: a history of the Communist International London 1939; Orwell’s reviews appeared in New English Weekly on June 9 1938, September 22 1938 and January 12 1939.↩︎

-

A Ciliga The Russian enigma London 1940.↩︎

-

M Eastman The end of socialism in Russia London 1938.↩︎

-

See the list in Orwell’s Collected works Volume 20, London 1998, pp259-86. However, Alex Zwerdling’s assertion that Orwell had learnt a lot from Trotsky’s The revolution betrayed must be treated with scepticism, because he claimed that Goldstein’s ‘book’ in 1984 is based on it. Even a cursory glance at The revolution betrayed and the relevant sections of 1984 proves that this assessment is quite inaccurate (see A Zwerdling Orwell and the left New Haven 1978, pp86-87).

It is remarkable that Isaac Deutscher, with his great knowledge of Trotsky’s writings, could declare that Goldstein’s ‘Book’ is “an obvious, though not very successful, paraphrase of Trotsky’s The revolution betrayed” (I Deutscher Heretics and renegades London 1955, p47). Irving Howe, who also should have known better, claimed that Goldstein’s ‘Book’ is “clearly a replica of Trotsky’s The revolution betrayed” (I Howe Politics and the novel New York 1957, p239. If anything, Goldstein’s ‘Book’ more resembles Deutscher’s strangely fatalistic, uncharacteristically un-Marxist schema of the rise of post-revolutionary elites: see I Deutscher Stalin: a political biography London 1949, pp173-76.↩︎

-

G Orwell The road to Wigan Pier, p189.↩︎

-

Ibid pp186-87.↩︎

-

G Orwell, ‘The English people’ Collected essays, journalism and letters Volume 3, Harmondsworth 1984, p22. Stephen Ingle correctly stated that “general principles of conduct” interested Orwell “more than political programmes” (S Ingle, ‘The politics of George Orwell: a reappraisal’ Queens Quarterly Spring 1973, p32).↩︎

-

W Wagar, ‘George Orwell as political secretary of the Zeitgeist’ in EJ Jensen (ed) The future of 1984 (Ann Arbor, 1984), p180.↩︎

-

B Crick George Orwell: a life Harmondsworth 1982, pp17-18.↩︎

-

G Orwell The road to Wigan Pier pp154-55, 189-95.↩︎

-

Ibid pp44, 117, 193.↩︎