17.04.2025

Life, death and resurrection

Easter Sunday is the most important date in the Christian calendar. After a short life packed full of miracles, their man-god died an agonising death on a Roman cross - only to rise, three days later, from Hades, born again. But, asks Jack Conrad, what about the real, flesh-and-blood Jesus?

By removing obvious fabulation, drawing on what we know about ancient Palestine, bringing out the class interests crouched behind the religious traditions, disputes and compromises, it is possible to establish a historically plausible Jesus. Given the importance of his myth in shaping western culture, a more than worthwhile exercise.

We are told that Jesus was raised in Galilee, a region with close linguistic, cultural and historical ties with Samaria and Judea in the south. Though dominated by peasant agriculture, the growth of opulent urban centres, such as Sepphoris and Tiberias, testify to the presence of a Hellenised minority, the commercialisation of life and intensified exploitation of the basic producers. The Romans extracted tribute either through client kings or direct rule. We know that class conflicts intensified and took the form of riots, social-banditry, guerrilla actions and on occasion full-scale revolt.

In the New Testament, the gospels of Matthew and Luke tell us that Jesus’ earthly ‘legal’ father was Joseph, a humble carpenter (Mark fails to mention him, while John does, but only once). Jesus - ie, Yeshua bar Yosef - must have been charismatic, self-confident and brave. Well educated too. Jesus was certainly a rabbi - a religious teacher and preacher. And during the course of his ministry, beginning in Galilee, he appears to have come to believe himself/aspires to be, not just a prophet, but the messiah (or anointed one), who would deliver the Jewish people from Roman rule (and end the days of the robber empires).

Jesus proved to be a superb political organiser, strategist and self-publicist. He spoke of himself as the ‘son of David’ or ‘son of god’. By saying this he certainly did not mean to imply that he was a man-god - a blasphemous concept for Jews. That is why two of the gospels - Matthew and Luke - are interesting, in that they leave in the family tree that purportedly proved that through Joseph he was biologically directly related to king David “14 generations” before (and all the way back to the first man, Adam).1 Luke iii provides a much longer list, compared with Matthew, and a genealogy which also contains many different names (passages in the Old Testament, such as 1 Chronicles iii,19, contradict both Matthew and Luke - so much for the ‘inerrancy’ of the Bible).

The prophet Micah had predicted that the messiah would be born in Bethlehem - the royal seat of the semi-mythical David. By placing his birth in this Judean town, Jesus and his early propagandists were proclaiming him to be the lawful king, as opposed to the Herodian upstarts.

It was like some canny medieval peasant leader announcing themselves to be the direct heir of Harold Godwinson and hence the true Saxon king of England against the Plantagenet or Angevine descendants of William of Normandy. Roman domination was initially imposed through Herodian kings, who were Idumean in background (ie, from the region to the south of Judea). Despite overseeing the building of the ‘second’ Temple in Jerusalem, they were widely despised as foreigners and Roman puppets. The Dead Sea scrolls exude an uncompromising rejection, disgust and hostility for the king - presumably Herod, or one of his successors. He is condemned as “boastful” and a “son of Belial”.2

Jesus’ claim to be ‘king of the Jews’ was unmistakably political. He was proclaiming himself to be the leader of a popular revolution that would bring forth a communistic ‘kingdom of god’. No pie in the sky when you die. The slogan, ‘kingdom of god’, was of this world and was widely used by fourth-party, zealot, sicarii and other such practical anti-Roman revolutionary forces, mentioned by Flavius Josephus, a near contemporary of Jesus.3 The ‘kingdom of god’ conjured up an idealised vision of the old theocratic system introduced by the Persian king, Cyrus, when he oversaw the return of the Jewish elite from their Babylonian exile in the 6th century BCE.

Their ‘kingdom of god’ would, though, see the poor gain and the rich suffer:

[B]lessed be you poor, for yours is the kingdom of god .... But woe unto you that are rich ... Woe unto you that are full now, for you shall hunger. Woe unto you that laugh now, for you shall mourn and weep.4

This imminent class retribution was not to be confined to Israel alone. The Jews were Yahweh’s revolutionary vanguard. Through them Jesus’ plan was for a universal utopia. From Jerusalem a “world theocracy”, with Jesus at its head, would redeem “all nations”.5 Then onwards peace reigns: swords are beaten into ploughshares and the wolf lies down with the lamb.

Samuel Brandon argued, crucially in his noted 1967 study, that Jesus and the zealots were part of the same revolutionary movement.6 In other words, they shared many of the same ideological aims and assumptions. Unmistakably true. Of course, Jesus was no zealot. He was an apocalyptic revolutionary, similar to John the Baptist, the essenes and their like. As Hyman Maccoby emphasises, Jesus “believed in the miraculous character of the coming salvation, as described in the writings of the scriptural prophets”.7 He was not interested in military strategy or tactics. Rome would be beaten without either conventional or guerrilla war. Nevertheless, though Jesus did not train his followers in the use of arms, five of his 12 inner circle of disciples clearly came from the ranks of the practical revolutionaries and retained guerrilla nicknames (including Peter Barjonah - ‘outlaw’; Simon - the zealot; James and John - the ‘sons of thunder’; and Judas Iscariot - the ‘dagger-man’).

This is not surprising. Jesus was no pacifist: “I come not to send peace, but a sword!”8 While liberation would have a military aspect, primarily it depended on supernatural assistance. There would be a decisive battle, where a tiny army of the righteous overcome overwhelmingly superior odds. In the Bible Gideon fought and won against the Midianites with only 300 men - he fancifully told the other 20,000 men in his army to “return home”.9 So the methods of Jesus and the guerrilla fighters differed, but were hardly incompatible. They differed on the degree that their strategy relied on divine intervention.

Either way, the zealots were unlikely to have actively opposed Jesus. He might have been a factional opponent, but he was no enemy. His mass movement would at the very least have been seen by the zealots as a sea to swim in - a tremendous opportunity to further spread their influence.

So Jesus did not stand aloof from the growing revolutionary movement that palpably existed in 1st century Palestine. On the contrary, he was its product and for a short time its personification.

The notion that Jesus opposed violence is a pretty transparent, later Christian invention, designed to placate the Roman authorities and overcome their fear that the followers of the dead man-god were dangerous subversives. The real Jesus would never have said “Resist not evil”. The idea is a monstrosity, fit only for the despairing appeasers. Jewish scripture is packed with countless examples of prophets fighting what they saw as evil - not least foreign oppressors. The real Jesus preached the ‘good news’ within the popular Jewish tradition against evil. He appears determined to save every ‘lost sheep of Israel’, including, perhaps, social outcasts and transgressors, such as the hated tax-collectors, for the coming apocalypse. Salvation depended on a total life change.

After the execution of John the Baptist Jesus reveals himself to be not simply a prophetic ‘preparer of the way’, but the messiah. “Whom say you that I am?” he asks his disciples. “You are the Christ,” answers Peter.10 This was an extraordinary claim, but one fully within the Jewish thought-world. He was not and would not have been thought of as mad. In biblical tradition there had been prophets and even prophet-rulers (Moses and Samuel). Jesus was claiming to be the messiah-king: ie, the final king. In Jesus the spiritual and secular would be joined. A bold idea, which must have “aroused tremendous enthusiasm in his followers, and great hope in the country generally”.11 Perhaps this explains why, after he was agonisingly killed on a Roman cross, the Jesus party refused to believe he had really died. His claimed status put him in terms of myth at least on a par with Elijah: he would return at the appointed hour to lead Yahweh’s chosen people to victory.

New Testament (re)writers are at pains to play down or deny Jesus’ assumed royal titles. Claiming to be ‘king of the Jews’ was to openly rebel against Rome. Instead they concentrate on terms like ‘messiah’ or ‘christ’, which they portray as being other-worldly. The Jews, and the disciples, are shown as not understanding such concepts, though they repeatedly occur in their sacred writings and had surely thoroughly internalised them. Nevertheless, the truth occasionally flashes through the fog of falsification and that allows us to make sense of Jesus’ short revolutionary career.

March on Jerusalem

The biblical account of the so-called transfiguration on Mount Hermon described in Mark involved no mere change in the “appearance” of Jesus’ “face” and “clothes”.12 No, it was the crowning (or anointing) of king Jesus by his closest disciples, Peter, James and John. Having trekked to the far north and into Syria-Phoenicia, one disciple seems to have crowned him, while the other two acted as the prophets, Moses and Elijah.13 Like the biblical Saul, David and Solomon, the new king was through the ceremony “turned into another man”.14

And, having been crowned, the prophet-king began a carefully planned royal progress towards his capital city, Jerusalem. The idea would have been to preach at each stop and build up a mass movement - a movement which we would expect to have been overwhelmingly made up of peasants longing for deliverance from oppression, exploitation and poverty. Jesus and his party promise, of course, not only to speak on behalf of the poor: they promise to practically bring about their salvation by cancelling debts, redistributing land and restoring the ancient covenant with Yahweh. A conservative-revolutionary message that clearly resonated.

Hence to understand the popularity of Jesus and his party we have to recognise the leader-follower dialectic - a determining relationship that cannot be ignored or skirted around, as is the case with standard Christian theology, which pictures Jesus as a strange man-god, urging people to pay their taxes and love their Roman and Herodian enemies. The real Jesus party would have done the exact opposite. Without that they would never have got a hearing, let alone a mass following - which in turn made them into an instrument of mass revolt.

From Mount Hermon the royal procession makes its way south, into Galilee, then over to the east bank of the Jordan and Peraea, before reaching Jericho. King Jesus is greeted by enthusiastic crowds and has already built up a sizeable entourage (which must have taken considerable organisation and substantial donations from rich sympathisers to maintain - five loaves and two fishes would not have been anywhere near enough). Jesus, note, not only preaches that the poor are to inherit the world: the rich must sell all they have - that or they will be damned to the fires of hell: “It is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the kingdom of god.”15

All the while Jesus has 12 close disciples acting for him - their number symbolising the traditional so-called 12 tribes of Israel. A kind of political committee/royal court. He also sends out before him 70 more into “every city and place” - 70 being a significant number in Jewish culture - the law-making council, the sanhedrin, had 70 members; Israel’s original top god, El, had 70 children, etc. Jesus performs many - prearranged? - miracles. The blind are given sight, cripples walk, etc (cities and towns were teeming with professional beggars, no doubt including the professionally crippled and blind). The suggestion that Jesus urged people to keep quiet about these nature-defying wonders is truly hard to swallow.

Finally, he triumphantly enters a swollen Jerusalem - either during the spring Passover or possibly in the autumn festival of the tabernacles. Pilgrims could double the normal population. Then there was the additional influx provided by the Jesus movement itself.

Symbolism is vital for all such apocalyptic revolutionaries. Jesus rides in upon an ass’s foal (thus fulfilling the prophesy of Zechariah ix, 9). There is no doubt what the masses think - pilgrims from the peasant countryside and native Jerusalem proletarians. They greet Jesus with unrestrained joy and proclaim him ‘son of David’ and ‘king of Israel’ - as argued, both revolutionary/royal titles. Palm branches are strewn before him and, showing their defiance of Rome, the crowd cries out, ‘Hosanna’ (save us).

With the help of the masses Jesus and his lightly armed followers force their way into the temple complex that crowns the city heights. Zealot and other fourth party militants perhaps play a role. Suffice to say, the religious police of the high priest are easily dispersed. Jesus angrily drives the venal sadducee priesthood out from the complex. They “have made it a den of robbers”.16 Meanwhile, the other priests carry on with their duties.

The Romans and their agents would have viewed these events as a nuisance rather than anything much else. Little rebellions at festival times were not uncommon. Nevertheless, in possession of the temple complex, Jesus and his followers were protected by the “multitude” from the poor quarter of the city. The priesthood is said to have been “afraid of the people”.17 It debated theology with Jesus, but could do no more.

Jesus fervently expected a miracle. There would be a tremendous battle: on the one side, the Romans and their quislings; on the other, his disciples alongside “12 legions of angels”.18 Jesus, his disciples and his angels will assuredly win. The defiled temple will then be destroyed and rebuilt in “three days”.19 Simultaneously, the dead rise and Yahweh, with Jesus sitting at his right hand, judge all the nations.

Jesus waited seven days for the apocalyptic arrival of god’s kingdom. It was expected to come on the eighth. At the last supper he expectantly says: “I will drink no more of the fruit of the vine [juice, not alcohol] until that day I drink it in the new kingdom of god.” Having taken himself to the garden of Gethsemane - just outside the temple complex and the city walls - Jesus prayed his heart out. But “the hour” did not arrive. A cohort of Roman soldiers (300-600 men) and the religious police did. Perhaps they were guided by the supposed turncoat Judas, perhaps not (Karl Kautsky, in his marvellous Foundations of Christianity [1908], says that the idea of anyone in the sadducee party of the high priests not knowing what Jesus looked like is just too improbable.20 In other words, the whole story of Judas and his ‘30 pieces of silver’ treachery is fake).

Trial and execution

Jesus was easily captured. (In Mark a naked, running, youth narrowly escapes - frankly, I do not have a clue what this aspect of the story is about. Were Jesus and his closest lieutenants about to carry out a miracle-bringing human sacrifice?21) It is a grossly unequal contest. His disciples only had “two swords”. “It is enough,” Jesus had assured them.22 There was a brief skirmish, according to the biblical account. Supposedly Jesus then says, “No more of this”, and rebukes the disciple, Simon Peter, who injured Malchus, a “slave of the high priest”. His right ear had been lopped off. Miraculously, Jesus heals him. Jesus is thereby presented as being opposed to bloodshed: “for all who take the sword will perish by the sword”.23 Obviously a fabricated interpolation. We have already seen Jesus promising cataclysmic violence and arming his followers, albeit with only two swords (the angels though would have been fully equipped for the final battle).

Interrogated by the high priest, Jesus was quickly handed over to the Roman governor, Pilate, as a political prisoner. Without fuss or bother Jesus was found guilty of sedition - he was forbidding the payment of Caesar’s taxes and had proclaimed himself king of the Jews.

Jesus - the real Jesus, that is - had no thought or intent of delivering himself up as a sacrificial lamb. He had expected an awesome miracle and glory, not capture and total failure. The gospels report his dejection and refusal to “answer, not even to a single charge”.24

Pilate was doubtless confronted by Jerusalem’s revolutionary crowd. It would have been demanding Jesus’ freedom, not crying, “Away with him, crucify him”.25 There was certainly no custom in occupied Palestine whereby the population could gain the release of any condemned prisoner “whom they wanted”.26 Pilate did not seek to “release him”. The notion of Pilate’s “innocence” is as absurd as the blood guilt of the Jews. Obviously yet another later, pro-Roman, insert.

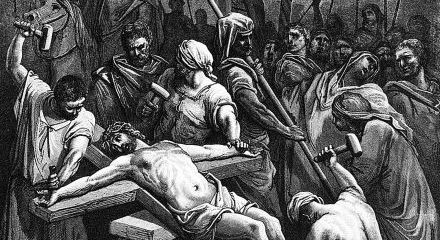

After whipping, beating and spitting upon him, Pilate had Jesus thrown into prison. Then, perhaps straightaway, perhaps after a number of months, he had him sent to an agonising death. Jesus was paraded through the streets, guarded by a “whole battalion”. Pilate’s plan was to humiliate the king of the Jews and demonstrate his powerlessness.

Jesus is stripped and a (royal) scarlet robe is draped over his shoulders. To complete the picture, a “crown of thorns” is mockingly planted on his head and a “reed” placed in his right hand.27 He is crucified along with two other rebels and derided by the Romans and their collaborating allies. Over his head, on Pilate’s orders, they “put the charge against him” - “This is the king of the Jews”.28

John has the chief priests objecting. That has the ring of truth. They wanted Pilate to write, “This man said he was king of the Jews”. Pilate has none of it. John puts these blunt words in his mouth: “What I have written I have written”.29 The last words of Jesus are heart-rending: ‘Eli, eli, lama sabachthani?’ (My god, my god, why hast thou forsaken me?)30 Yahweh had not acted. There were no angels, no last battle. Jesus was a brave revolutionary, who wrongly staked all on divine intervention.

There are supposedly miraculous happenings at his moment of death. Saints rise from their graves and walk about. There are earthquakes. The curtain in the temple is torn in two. Even more preposterous, the Bible has it that it is the Roman centurion and guard who are first to declare that the man they have just killed is “Truly son of god”.31 Actually for them it was just like any other day’s work. The execution of rebel ringleaders was a common occurrence for the Roman garrison.

The Roman execution of Jesus surely came as a stunning shock. His followers must have been mortified. Nevertheless the Jesus party survives the death of its founder-leader. Indeed it grows rapidly. The Acts report a big increase from 120 cadre to several thousand in the immediate aftermath of his crucifixion. These core recruits were, of course, fellow Jews - including perhaps not a few essenes, baptists and guerrilla fighters. People undoubtedly inspired by Jesus’ attempted apocalyptic coup and the subsequent story that his body had disappeared and had, like Elijah, risen to heaven (the Romans blamed his disciples, saying they had secretly removed the corpse from its tomb - a slightly more likely scenario). All fervently expected imminent deliverance through the return of Jesus: “the time is fulfilled and the kingdom of god is at hand”.32 That remains official Christian doctrine, though for most the second coming, the parousia, is no longer imminent. Incidentally, the Shia tradition of Islam has something similar. It still awaits the return of Abul-Qassem Mohammed, the 12th imam, the mahdi, who ‘disappeared’ in 941.

Anyway, the social atmosphere in 1st century Judea was feverish. People must also have been desperate - after all, they were banking on a dead leader and the armed intervention of Yahweh’s legions of angels. The party, commonly called the nazarenes or nazoreans, was now led by James - the brother of Jesus. This is hardly surprising. The followers of Jesus presented him as king of the Jews. He was, they claimed, genealogically of David’s line. The election of James was therefore perfectly natural in terms of continuity and inheritance. The nazorean tradition being closely followed by some Muslims: Abdullah II of Jordan and Rahim al-Husseini, the Aga Khan, are supposedly able to trace their lineage directly back to the prophet, Mohammed, himself.

Jesus, James, Paul

Surely it is a sound argument that to know James is to know Jesus. Who would be more like Jesus in terms of beliefs, expectations and practices? His closest living relative, who is chosen by Jesus’ cadres as his successor? Or Paul, who never saw Jesus alive, only in visions? Who defended and continued Jesus’ programme? Was it James and other intimates in Palestine? Or was it Paul, a Roman citizen, who, as Saul or Saulus, admits he was a persecutor of Jesus’ followers? Suffice to say, all Christian churches maintain that it was the latter. Paul, with his convenient dreams and reliance on the doctrine of faith, was apparently more in touch with the authentic Jesus - the so-called Christ in heaven - than James and the family of Jesus.

To establish this reversal of common sense, and reality, the gospels go to great lengths to denigrate the family of Jesus, his brothers and disciples. They are constantly belittled, portrayed as stupid and lacking in faith. “I have no family,” says the Jesus of the gospels. The disciples are repeatedly chided for failing to understand that Jesus and his kingdom are “not of this world”. Peter famously denies Jesus three times before the cock crows due to lack of faith. Etc, etc.

Although James is elected head of the Jerusalem community and was also supposedly of the Davidic family line, he is almost entirely absent from the Christian tradition. He has been reduced or cut out altogether, so embarrassing is he. Nor does James appear in the Koran - though Muslim dietary laws are based on his directives set out for the overseas communities, as recorded in the Acts.33 Arabs were being drawn to monotheism long before Mohammed - and the ideological influence of the Jews (and perhaps the nazoreans) is unmistakable in Islam.

The gospels, as they come down to us, have obviously been overwritten to remove or downgrade Jesus’ family, not least his brother and successor. James peers out as a shadowy figure, as if through frosted glass. Sometimes he is disguised as James the Lesser, in other places as James, the brother of John, or James, the son of Zebedee. Such characters make a cursory and insubstantial appearance in the gospels. However, James does suddenly pop up in the 12th book of the Acts as the main source of authority in Jerusalem. Evidently his other obscure titles are due to redaction. Paul’s letters openly acknowledge the true relationship between James and Jesus. James is straightforwardly called “the brother of the lord”.

Not surprisingly, church fathers faced acute problems. The more ethereal Jesus is made, the more James sticks out like a sore thumb. Origen (185-254) therefore roundly attacked those of his contemporaries who, on the basis of reading Josephus, unproblematically credited James with being biologically related to Jesus, and fantastically linked the fall of Jerusalem in 70 with the death of James rather than Jesus. In Contra Celsus Origen quotes from what we now know are forged passages inserted into in Josephus’s Jewish antiquities:

Now this writer, although not believing in Jesus as the Christ, in seeking after the cause of the fall of Jerusalem and the destruction of the temple, whereas he ought to have said that the conspiracy against Jesus was the cause of these calamities befalling the people, since they put to death Christ, who was a prophet, says nevertheless - being, although against his will, not far from the truth - that these disasters happened to the Jews as a punishment for the death of James the Just, who was a brother of Jesus (called Christ) - the Jews having put him to death, although he was a man most distinguished for his justice. Paul, a genuine disciple of Jesus, says that he regarded this James as a brother of the lord, not so much on account of their relationship by blood, or of their being brought up together, as because of his virtue and doctrine. If, then, he says that it was on account of James that the desolation of Jerusalem was made to overtake the Jews, how should it not be more in accordance with reason to say that it happened on account (of the death) of Jesus Christ, of whose divinity so many churches are witnesses, composed of those who have been convened from a flood of sins, and who have joined themselves to the creator, and who refer all their actions to his good pleasure.34

In book two of his Church history Eusebius (260-340), bishop of Caesarea in Palestine, cites Josephus in a similar vein:

James was so admirable a man and so celebrated among all for his justice, that the more sensible even of the Jews were of the opinion that this was the cause of the siege of Jerusalem, which happened to them immediately after his martyrdom for no other reason than their daring act against him …. Josephus, at least, has not hesitated to testify this in his writings, where he says, These things happened to the Jews to avenge James the Just, who was a brother of Jesus, that is called the Christ. For the Jews slew him, although he was a most just man.35

Obviously we must discount the idea that Josephus authored anything about Jerusalem being destroyed because the Jews bear collective guilt for the death of James (as they are supposed to have done for the killing of Jesus in official church doctrine). That said, while Eusebius unambiguously writes of the election of James, like Origen, he too seeks to divorce Jesus from all earthly biological relations:

Then James, whom the ancients surnamed ‘the Just’ on account of the excellence of his virtue, is recorded to have been the first to be made bishop of the church of Jerusalem. This James was called the brother of the lord because he was known as a son of Joseph, and Joseph was supposed to be the father of Christ, because the virgin, being betrothed to him, was found with child by the holy ghost before they came together, as the account of the holy gospels shows.36

Eusebius was prepared to grant that the New Testament letter of James, “the first of the so-called Catholic epistles”, might be used for instructional purposes, but questioned its authenticity.37 For Robert Eisenman, one of the translators of the Dead Sea scrolls, this was in part because “its content and theological approach were so alien to him”.38 It exudes wonderful class hatred and promises the certainty of retribution: “Come now, you rich, weep and howl for the miseries that are coming upon you.”39

In the 4th century Jerome finally decides that Jesus and James were cousins. In other sources too the relationship is distanced. Jesus’ brothers, including James, become half-brothers, stepbrothers or milk brothers. A theological construction carried over into the Koran by Mohammed and his followers in the 7th century. A divine Jesus has no need for an earthly father, uncles, brothers or sisters. There is also the growing cult of Mary’s perpetual virginity. Joseph could not have had any children with her. Augustine, in the 5th century, firmly establishes this as Catholic doctrine. Jesus thereby becomes what Sir James Frazer called a “dying and reviving god” like Adonis, Attis, Dionysus and Osiris.40

That does not mean James cannot be restored to his rightful place. We can unearth James and in so doing his brother, Jesus, also comes into fuller view. Actually the most reliable biblical testimonies concerning James and his role in the nazorean party can be found in Paul’s letters. Given all we know, they seem to be accurate enough - above all because they paint a picture of conflict between Paul and James.

Paul, repeatedly, disagrees with the rulings on diet, circumcision and observation of Jewish laws and taboos handed down by the Jerusalem council. Paul even denigrates what he calls “leaders”, “pillars”, “archapostles” and those “who consider themselves important” or “write their own references”.41 In other words, the apostles - chief amongst them James. Paul freely admits those leaders whom he calls Peter and Cephas were willing to defer to the authority of James.42

Other gospels

So the relationship between Jesus and James and the latter’s standing is attested to in the Acts and Paul’s letters. In them and tangential gospel accounts we find that, besides James, there were three other brothers of Jesus - they are called Simon, Jude and Joses. A sister, Salome, is also mentioned in Matthew. Furthermore, where the established canon is evasive or eerily silent about James, the early and non-canonical (gnostic) gospel of Thomas puts these words into the mouth of Jesus. Having been asked, “who will be great over us” after “you have gone?”, ‘Thomas’ has Jesus say this: “In the place where you are to go, go to James the Just, for whose sake heaven and earth came into existence.”43 The mystical gnostics, it should be noted, credited James with supernatural powers. Of course, it is not that the gospel of Thomas (written in Coptic in something like 90) should be thought of as historically reliable. It is full of mythological invention. What distinguishes its account is simply that in certain key areas it is not inverted by the same mythology as the standard versions.

A profusion of other gospels are known to have existed before the New Testament was finalised with Constantine, and the incorporation of the church as an arm of the Roman state. Scholars imagine a single source, the so-called Q gospel (Q standing for ‘Quelle’ which means ‘source’ in German). It was apparently written in the 50s.44 Fragments were discovered in the Egyptian desert. But there could conceivably have been many sources. We know that other gospels were written and some still exist in whole or part. Eg, the gospel of Ebonites, the gospel of Philip, the gospel of the Hebrews, the gospel of Mathias, the gospel of Peter, the gospel of Mary, etc.45 It is said by upright Christians that they lacked historical and literary merit and thereby “excluded” themselves “from the New Testament”.46 Clearly untrue. Such gospels were destroyed, driven underground or marginalised because they contradicted established Christian doctrine ... not least when it came to James. From them and other such literature we certainly learn that James plays a role of “overarching importance”.47

There is further evidence about the standing of James to be found in the writings of Epiphanius, bishop of Salamis, (c310/20-403) and the priest and saint Jerome (347-420). Epiphanius suggests that James was appointed directly by Jesus from the heights of heaven. Hence James was the “first whom the lord entrusted his throne upon earth”. Jerome too provides an account of how James was either “ordained” or “elected” as bishop of Jerusalem.48 By their own admission these authors base themselves on earlier sources - writers whose works have either been destroyed or lost. Eg, Hegesippus (c90-180), a church leader in Palestine, and Clement of Alexandria (c150-215). There is another Clement (c30-97), this time of Rome, whose name was attached to what we now know as the Pseudoclementine (‘pseudo’ as in ‘falsely attributed’).

Works such as the Recognitions of Clement, as Eisenman reminds us, are “no more ‘pseudo’” than the gospels, Acts and the other Christian literature we now possess from that period.49 Eg, none of the now standard four gospels were authored by a single individual - hence we certainly have a Pseudomatthew, a Pseudomark, a Pseudoluke and a Pseudojohn. Revealingly, though the account of the Pseudoclementine material is highly mythologised: it includes letters purportedly from Paul to James and from Clement to James. James is straightforwardly addressed as “bishop of bishops” or “archbishop”. So there is not a shadow of doubt that James served as leader of the Jesus party after the death of his brother and remained in that post till his own execution in 62 (he was succeeded by Cephas, a first cousin).

Strangely, the Acts exhibit a highly significant silence about the election of James - surely a defining moment for the post-Jesus nazorean movement. The first chapter, which deals with the replacement of Judas Iscariot after his purported treachery and suicide, is a crude mythical invention - Judas is in all probability Jude: ie, one of the brothers of Jesus. That aside, the story of the “eleven” getting together to elect another apostle is in all likelihood a cynical overwrite for the election of James. In the Acts it is rather a non-event, with which to begin the official history of the early church. “Mattias” is chosen, after the casting of “lots”, over “Joseph called Barabas”.50 The redactors were determined to blacken the name of Jesus’ closest associates or remove them where they could. There is a striking parallel here to the way Stalin’s propagandists demonised or airbrushed out Kamenev and Zinoviev and other members of Lenin’s inner circle after his death.

Whatever the exact truth, an obvious question presents itself. Why was the early church so eager to play down or obliterate the role of James? We have already touched upon the embarrassment concerning the blood relationship between Jesus and James. But there was more to it than that. The answer, already in part alluded to, is threefold.

Firstly, James, the successor of “the lord”, has to be counted amongst those who opposed the Roman oppressors. That in turn would put Jesus in the same camp as the Jewish revolution. The Jesus party, headed by James, took an active role - perhaps a leading one - in preparing the ground for the great anti-Roman uprising of 66.

Secondly, James exhibited neither in thought nor practice the slightest trace or hint of Christianity. He was single-mindedly, not to say fanatically, Jewish. He observed the minutiae of Jewish religious law and demanded that other Jews did the same.

Thirdly, there is abundant evidence that there was a fundamental and acrimonious schism between the community led by James and Paul - who having concocted “weird religious fantasies partially from Judaism and partially from Hellenism”, so as to transform the death of Jesus into a “cosmic sacrifice”, was the real “founder of Christianity as a new religion”.51 Note, besides Hyam Maccoby, “countless” other historians likewise recognise Paul as the real founder of Christianity.52

None of this would have been to the liking of the early church.

Nazoreans

The seething discontent that characterised the period from the imposition of Roman direct rule in 6 to the revolution of May 66 worked like a social acid on the old methods of control and produced a crop of courageous messiahs who found themselves a substantial following. Josephus, an upper-class Jew, mentions a handful by name or title - eg, Theudas, a “false” prophet from Egypt - but all the indications are that as a type they were numerous. After the defeat of one, another arose. Some - for example, John the Baptist, who, though he never claimed to be the messiah, led a messianic movement - were relatively peaceful. Though such “religious frauds” did not “murder”, Josephus calls them “evil men”. They were “cheats and deceivers” and “schemed to bring about revolutionary changes”. The Romans typically responded by sending in troops. John was beheaded by order of Herod Antipas. Others fought fire with fire. These “wizards” gained “many adherents”, reports Josephus. They agitated for the masses to “seize” their “liberty” and “threatened with death those that would henceforth continue to be subject and obedient to the Roman authority”. There was an unmistakable class content. The “well-to-do” were killed and their houses “plundered”.53

Clearly there existed a blurred line between the rural revolutionary and the criminal rebel. Kautsky draws a parallel between 1st century Palestine and the situation in 1905-08 Russia, when anarchist bands looted the countryside. We in our time have seen similar manifestations occur in Northern Ireland. Mainstream loyalist and fringe republican paramilitaries indulge in drug-running, protectionism and plain theft. Certain individuals enrich themselves and live in plebeian luxury.

Having said that, it is clear that Josephus, just like present-day establishment political, media and business figures, cannot but concede the moral superiority of revolutionaries who give their all fighting for the interests of those below: eg, Rosa Luxemburg, John Maclean, James Connolly, Antonio Gramsci, Che Guevara. Josephus wants to dismiss them as mere bandits. But they are, he grudgingly admits, prepared to suffer torture rather than submit. Josephus himself fatefully chose the slippery road of treachery and moral surrender. Having fought as a military commander in the first phase of the Jewish revolution, he defected to the Romans and eventually appears to have come to a sticky end in Rome.

From Josephus it is clear that the masses were not united behind a single party leadership. Yet, inhabiting the rarefied atmosphere of the aristocracy, Josephus would have had only the vaguest knowledge of the politics of the extreme left of his day. One should take his description as a rough sketch, on a par with the excruciating caricatures of the left that occasionally come from the more intelligent writers in the mainstream bourgeois media. Instinct alone tells us that mass politics in 1st century Palestine were far more variegated than described by Josephus. In the Talmud we find the claim that “Israel did not go into captivity until there had come into existence 24 varieties of sectaries”.54 A pared down version of the modern 57 varieties quip.

Where do James and the post-Jesus nazoreans fit in here? They were apocalyptic revolutionaries only different from the movement founded by John the Baptist, in that they could confidently name the messiah. It was surely another advantage that their man had safely risen to heaven. He was still alive and could neither be captured nor killed. Jesus would come and deliver his people at the appointed hour (in this respect the nazorean story of king Jesus is akin to the British myth of the sleeping king Arthur).

The potency of this Elijah-like combination is shown in the Acts. Seven weeks after the crucifixion of Jesus the nazorean party was gaining many recruits and was widely acclaimed by a Jewish population that had, according to the gospels, just been clamouring for his death. Here is what Acts says:

And all that believed were together, and had all things in common; and sold their possessions and goods, and distributed them to all, as any had need. And day by day, attending the temple together and breaking bread in their homes, they partook of food with glad and generous hearts, praising god and having favour with all the people. And the lord god added to their number day by day those who should be saved.55

Acts was composed in the second half of the 1st century and is overtly Pauline. Nevertheless, though an apologia for Paul and unmistakably Christian, Acts not only shows the communistic nazoreans finding “favour with all the people”: as a community the party uses and worships in the Jerusalem temple. Evidently the nazoreans were neither Christian nor Jewish-Christians. They were Jews by birth and Jews by conviction. Hence they diligently kept the laws of Moses and observed the Sabbath. So we should not see the nazoreans as revolutionaries when it came to social values. On the contrary, they were strictly conservative - traditionalists who denounced the transgressions, immorality and clawing greed of the upper classes.

James - their prince regent - in particular was renowned for his saintly devotion. Jerome refers to a story about James, which says that such was his religious fame that people “earnestly sought to touch the hem of his clothing”.56 Eusebius quotes Hegesippus (c110-c180) and his now lost Memoirs (book five). So frequently did James pray that his knees became “hard like those of a camel”. As with the most extreme Jews of his day, he “drank no wine nor strong drink, nor did he eat flesh”. Furthermore James seems to have taken a vow of celibacy in order to preserve his ‘righteousness’ (zaddik in Hebrew). “[H]e was holy from his mother’s womb.” So it was James, not Mary, who was the perpetual virgin. Making sure no-one missed his holiness, “he wore not woollen, but linen, garments” and refused to use a “razor on his head”. 57

Besides such evidence we can also arrive at similar results from passages in the Acts and Paul’s letters to the Galatians and Corinthians, albeit using simple inference. For example, unlike the “pillars” in Jerusalem, Paul tells his followers that they can eat “everything sold in the meat market”.58 He also instructs Jews to break the taboo outlawing table fellowship with gentiles. The biblical image of Jesus magically transforming water into wine, the man-god who like a heathen equates the bread and wine of the last supper with his body and blood, and who freely associates with prostitutes and Roman centurions, was unmistakably designed to produce apoplexy amongst the nazoreans. A deliberately insulting reversal of their beliefs, laws and attitudes.

It is of the greatest significance that Jerome and Eusebius insist that James wore the mitre of the high priest and actually entered the inner sanctum, or ‘holy of holies’, in the Jerusalem temple. “He alone was permitted to enter into the holy place,” says Eusebius (by tradition no-one apart from the high priest, who enacted the annual Yom Kippur ritual there, was allowed in).59 So it appears that James functioned as an opposition (righteous or zaddokite) high priest. Whether he stood before the ark in the ‘holy of holies’ just once or on a regular, annual basis is a moot point.

Either way, James could only have crossed the threshold of the inner sanctum, to pray for the people on Yom Kippur, if he had the active support of the masses. In other words, against the morality, ritual and the feeble statelet wielded by the high priesthood there stood another power - the morality, ritual and mobilised masses of the fourth philosophy. Put yet another way, Jerusalem was gripped by dual power. Josephus candidly admits that there was “mutual enmity and class warfare” between the high priests, on the one hand, and the “priests and leaders of the masses in Jerusalem, on the other”.60

With all this in mind it is hardly surprising that the nazoreans were still overwhelmingly lower class. One of their party names - along with the Qumran community - was ‘the poor’. This social composition continued after the first beginnings and is referred to by Paul in his first letter to the Corinthians:

[N]ot many of you were wise according to worldly standards, not many were powerful, not many were noble of birth; but god chose what is foolish in the world to shame the strong, god chose what is low and despised in the world, even things that are not, to bring to nothing things that are, so that no human being might boast in the presence of god.61

The plebeian character of the nazorean mass base perhaps explains why we possess so little direct evidence of exact organisation and ideology. The leaders were surely persuasive, eloquent and educated. But their party culture was oral, not written. Alan Millard is surely right, however, when he argues that first-hand written reports, even if they were just rough notes, about Jesus “could have been made during his lifetime”.62 Nonetheless, while such material could have made its way into the gospels, we have no hard evidence as to whether or not that happened. Either way, the rank and file were overwhelmingly illiterate. The teachings and sayings of Jesus were therefore transmitted orally and that afforded considerable room for exaggeration and downright fabrication.

However, being seared into the minds of even the most unsophisticated amongst the congregation, the most famous phrases and stories could not be easily expunged by later redactors. Eg, Acts tells of a well-off married couple, Ananias and Sapphira, who, having joined the nazoreans, “kept back some of the proceeds” from the sale of their property.63 They both instantly fall down dead when reproached by the apostles. In Luke we read that a man “clothed in purple and fine linen” goes to Hades and “torment” and the “flames” simply because he is rich. The poor man, Lazarus, in contrast finds comfort in “Abraham’s bosom”.64 The letter of James, written in the 1st century, is, as we have seen, full of loathing for the rich, once again simply because they are rich. The poor have been “chosen by god” to be “heirs of the kingdom which he has promised”. The rich “oppress you”, “drag you to court” and “blaspheme”, says James.65 The poor are urged to await the “coming of the lord” and class revenge.

Almost immediately after the execution of Jesus, his party finds a remarkable response to their message in the poor quarters of Jerusalem. Their headquarters were situated in a district called Ophel in the cramped lower city. The atmosphere must have been close to collective madness. There is ecstatic talk of miracles and cures; of the coming messiah and ending Roman rule. In modern terminology, the masses refuse to be ruled in the old way. Recruits came in their thousands and the better off brought all their possessions with them. The nazorean leaders address huge crowds from the steps of the temple - only the temple enclosure has space enough to accommodate those who want to hear them. Any fear that might have demoralised them or held them back after Jesus was executed, vanishes. The masses breathe courage into the cadre. Psychologically they become inspired. The ‘spirit’ is upon them.

The sadducees respond by having the religious police arrest those whom the Acts call Peter and John. They were preaching resurrection - Jesus being their proof. But the actual interrogation that followed the next day concerns the healing of a cripple. He is hauled in as a witness. The apostles refuse to be intimidated and boldly proclaim the name of their messiah. No religious or state crime has been committed, or so they reportedly maintain. The high priest made threats, but he decides to release them “because of the people”.66 The nazoreans had scored an important tactical victory and were further emboldened. Some 5,000 more purportedly join their ranks.

Not long after, worried by the ever increasing numbers attracted to the nazorean meetings in the temple enclosure, the high priest and sadducees have all the apostles arrested and confined to a “common prison” - presumably the temple dungeon.67 However, when the religious police go to fetch them for interrogation, they are horrified to discover them gone, vanished, flown. Presumably sympathisers, not an angel, had sprung them. Far from keeping heads down, the apostles are once again found “standing in the temple and teaching the people”.68 Without violence, “for they are afraid of being stoned by the people”, the guards bring them before the sanhedrin (the 70-strong supreme religious council). They are ordered to stop their preaching. Speaking on behalf of them all, Peter refuses. A pharisee named Gamaliel eloquently urges caution. So, after roughing them up and warning them not to “speak in the name of Jesus”, they “let them go”.69 Again to no effect. Every day nazoreans continue their meetings at private homes and in the temple enclosure.

It is in this context that the Acts introduce Stephen (a Greek name). The sadducees have him seized and falsely accused of blasphemy. Stephen defends himself bravely, but, deaf to his pleas, they have him stoned to death.

There is, we know, an interregnum in terms of the Roman power structure in 36-37 with the departure of Pilate and the preparation for war against the Arabs. Under such conditions Jonathan, the high priest, exercises greater autonomy. The Acts report that Saul (Paul) takes a lead not only in the killing of Stephen, but in the “great persecution” against the “church in Jerusalem”, initiated by Jonathan, that followed. Robert Eisenman disputes the veracity of the Stephen story. He argues at length, and persuasively, that the martyrdom of Stephen is an overwrite for an attempt on the life of James.

Eisenman reckons that James was attacked by Paul and a gang of hired thugs, who participated in Jonathan’s pogrom against the nazoreans and other oppositionists. We find confirmation of this thesis in the Pseudoclementine. A grand debate in the temple enclosure between the sadducean hierarchy, the pharisees, the baptists, the Samaritans and the nazoreans headed by James is reported in tit-for-tat detail. Of course, the nazoreans are presented as winning the argument hands down. So, on the second day of the debate, presumably at a prearranged moment, Saul (Paul) and his men stage a riot. Book one of Recognitions contains the following account:

[H]e began to drive all into confusion with shouting, and to undo what had been arranged with much labour, and at the same time to reproach the priests, and to enrage them with revilings and abuse, and, like a madman, to excite everyone to murder, saying, “What do ye? Why do ye hesitate? Oh sluggish and inert, why do we not lay hands upon them, and pull all these fellows to pieces?” When he had said this, he first, seizing a strong brand from the altar, set the example of smiting. Then others also, seeing him, were carried away with like readiness. Then ensued a tumult on either side, of the beating and the beaten. Much blood is shed; there is a confused flight, in the midst of which that enemy attacked James, and threw him headlong from the top of the steps; and supposing him to be dead, he [Saul‑Paul] cared not to inflict further violence upon him.70

Though with both legs broken, James survives. He retreats to Jericho, along with 5,000 followers. The standard narrative then proceeds with Saul (Paul) in chase - with the blessing of Jonathan the high priest - and then having his vision of Jesus and losing his sight for three days. He then turns nazorean and later adopts the Latinised form of his name.

Paul proves himself brilliant when it came to winning non-Jews to convert to a sympathising level of Judaism. Full conversion involved circumcision and observance of all of the laws and taboos. ‘God-fearers’ or ‘proselytes of the gate’ were a kind of partial or half-way conversion. They were not required to undergo circumcision nor change their nationality. God-fearers only had to accept the seven laws of the sons of Noah and revere the Jews as a ‘nation of priests’.

First Christians

It is his converts who are first called Christians. Possibly James encouraged Paul to take up missionary work abroad, when he presented himself to the Jerusalem council three years after his road-to-Damascus ‘experience’. Paul says he tried to see the apostles, but only met “James the brother of the lord”.71 He travelled to Cyprus, Galatia, Syria, Macedonia and Greece and persuaded many of the uncircumcised to accept Jesus as redeemer. Yet so determined was Paul to maintain the growth of his overseas communities that he embarks on a process of whittling away the specifically Jewish elements of the faith.

As numbers ballooned a Christian bureaucracy emerged from amongst the elite of self-sacrificing enthusiasts. The most talented propagandists became full timers. Deacons were chosen to oversee common meals, look after places of worship and manage the finances needed to support the professional preachers, the widows and orphans, the prisoners and the visiting strangers. Soon came the appointment of bishops in Damascus, Antioch, Athens, Carthage, Alexandria and Rome. Though not the representative of this bureaucracy, Paul paved the way in terms of theology. At first his programme would have been no more than implicit, a tendency. Laws and taboos should be moderated, not discarded. However, soon his teachings start to explicitly diverge from nazoreanism and Judaism itself.

Paul’s mature views are to be found in his letters or epistles. Written some time in the 50s and 60s, they are in the most part considered “the genuine work of Paul”.72 This Pauline material forms the earliest texts contained in the New Testament. In them we find Paul expounding upon the divine nature of Jesus. The death of Jesus is recounted in terms of the death and rebirth of a man-god.

By the 2nd century we have direct evidence of Christians celebrating Pascha (Easter) with Jesus being presented as the Passover lamb who willingly sacrifices himself in order to redeem humanity. In his First Epistle to the Corinthians, Paul had already said: “Cleanse out the old leaven that you may be a new lump, as you really are unleavened. For Christ, our paschai lamb, has been sacrificed.”73

Paul effectively dismisses Jewish laws as outdated and believes that the distinction between Jew and gentile ought to be abolished. He openly courts the Romans and the powers-that-be. Christian doctrine is still underdeveloped. There is no trinity, no virgin birth. But what we know as the gospels of today owe their Hellenistic mysticism and pro-Romanism to Paul. With his innovations acting as mediation, the whole Jesus story is gradually retold and turned into something entirely at odds with the nazorean tradition. The only nazorean document in the New Testament that survives the Pauline revision more, rather than less, intact, is the letter of James. Presumably due to its fame.

Fantastic Reality - Marxism and the politics of religion by Jack Conrad can be purchased or downloaded free from communistparty.co.uk/resources/library/jack-conrad

-

Matthew i,17.↩︎

-

R Eisenman and M Wise The Dead Sea scrolls uncovered Longmead 1992, p65.↩︎

-

Josephus writes of a “fourth philosophic sect” that gained “a great many followers” in 1st century Palestine (F Josephus Jewish antiquities Ware 2006, p774). The other three parties were the sadducees (high priest conciliators of Roman imperialism), pharisees (accommodating religious intelligentsia) and the essenes (camp-dwelling apocalyptic communistic revolutionaries).↩︎

-

Luke vi,20-25.↩︎

-

H Schonfield The passover plot London 1977, p24.↩︎

-

See SGF Brandon Jesus and the zealots Manchester 1967.↩︎

-

H Maccoby Revolution in Judea London 1973, pp157‑58.↩︎

-

Matthew x,34.↩︎

-

Judges vii,2.↩︎

-

Mark viii,29. ‘Christ’, Greek for ‘anointed one’ (ie, messiah).↩︎

-

H Maccoby Revolution in Judea London 1973, p163.↩︎

-

thebiblejourney.org/biblejourney1/5-jesuss-journeys-beyond-galilee/jesus-is-changed-on-the-slopes-of-mount-hermon.↩︎

-

Mark ix,4.↩︎

-

I Samuel x,6.↩︎

-

Mark x,25.↩︎

-

Mark xi,17.↩︎

-

Mark xi,32.↩︎

-

Matthew xxvi,53.↩︎

-

Matthew xxvi,62.↩︎

-

K Kautsky Foundations of Christianity New York NY 1972, p367.↩︎

-

Morton Smith, a Columbia university academic, claimed in 1958 to have discovered a longer version of Mark, found in a letter allegedly written by Clement of Alexandria. The running youth is there, of course. In Smith’s account, however, Jesus, a magician and miracle-worker, had, as was his practice, just baptised him during a secret nocturnal ceremony. A mystical experience that allowed them both to ascend to heaven and brought about spiritual and physical union of the two of them. In other words, Jesus had sex with those whom he baptised. Understandably, Smith attracted a lot of attention and it turns out that his long version of Mark somehow disappeared in 1990, leading to all manner of - largely well founded - speculation about its authenticity and, not surprisingly, accusations of forgery and Smith perpetrating a hoax (see M Smith Clement of Alexandria and the secret gospel of Mark Cambridge MA, 1973).↩︎

-

Luke xxii,38.↩︎

-

Matthew xxvi,52.↩︎

-

Matthew xxvii,14.↩︎

-

John xv,19.↩︎

-

Matthew xxvii,15.↩︎

-

Matthew xxvii,28.↩︎

-

Matthew xxvii,37.↩︎

-

John ixx,21,22.↩︎

-

Mathew xxvii,46.↩︎

-

Matthew xxvii,54.↩︎

-

Mark i,14-15.↩︎

-

Acts xv,20-29.↩︎

-

Ibid.↩︎

-

Ibid.↩︎

-

R Eisenman James the brother of Jesus London 1997, p3.↩︎

-

James v,1.↩︎

-

J Frazer The golden rough: a study in magic and religion Ware 1993, p386.↩︎

-

Galatians ii,9 and I Corinthians iii,1-9; v,12; viii,1; x,12; etc.↩︎

-

Galatians ii,10-12.↩︎

-

Thomas xii.↩︎

-

See BL Mack The lost gospel Shaftsbury 1993.↩︎

-

See NR James The apocryphal New Testament Oxford 1969.↩︎

-

Ibid ppxi-xii.↩︎

-

R Eisenman James the brother of Jesus, London 1997, p75.↩︎

-

Quoted in ibid p200↩︎

-

Ibid p71.↩︎

-

Acts i,23-26.↩︎

-

H Maccoby The mythmaker: Paul and the invention of Christianity New York NY 1986, p204.↩︎

-

James D Tabour writes that “countless books have been written in the past hundred years arguing that Paul is the ‘founder” of Christianity”. Besides his own Paul and Jesus (2012), he cites Joseph Klausner’s, From Jesus to Paul (1942), as still being worth a look. But there are many others besides: eg, Albert Schweitzer’s The mysticism of the Paul the Apostle (1931), Gerd Lüdemann’s Paul the founder of Christianity (2001), Hugh Schonfield’s Those incredible Christians (1969) and Barrie Wilson’s How Jesus became Christian (2008).↩︎

-

R Eisenman James the brother of Jesus, London 1997, p75.↩︎

-

Quoted in H Schonfield The Pentecost revolution Shaftsbury 1985, p259.↩︎

-

Acts ii,44-47.↩︎

-

Quoted in R Eisenman James the brother of Jesus London 1997, p239.↩︎

-

1 Corinthians x,25.↩︎

-

Quoted in R Eisenman James the brother of Jesus London 1997, p318.↩︎

-

1 Corinthians i,26-30.↩︎

-

AR Millard Reading and writing at the time of Jesus Sheffield 2001, p12.↩︎

-

Acts v,2.↩︎

-

Luke xvi,19.↩︎

-

James ii,5-7.↩︎

-

Acts iv,21.↩︎

-

Acts v,18.↩︎

-

Acts v,25.↩︎

-

Acts v,40.↩︎

-

web.archive.org/web/20150416140128/www.compassionatespirit.com/Recognitions/Book-1.htm.↩︎

-

Galatians i,19.↩︎

-

H Maccoby Revolution in Judea London 1973, p235.↩︎

-

1 Corinthians v, 7-8.↩︎