28.03.2024

Messiahs and money men

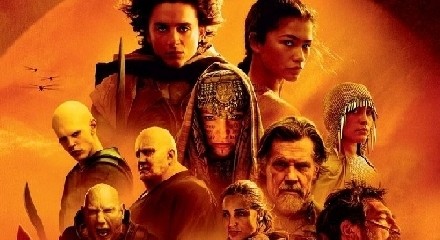

Harley Filben reviews Denis Villeneuve (director) Dune: part two 2024, general release

There is a moment quite far into Dune: part two where the antagonists - an imperialist army composed of horrifyingly identical, hairless, pale homunculi - bombard the home settlement of our plucky heroes.

A spaceship, a wall of darkest-grey metal, pounds ordnance into a desert rock formation. We viewers know it as ‘Sietch Tabr’, under which a colony of the oppressed people, the Fremen, have made their home. We have observed their funerary rituals, of removing the moisture from the corpses of their dead and pouring it into an underground pool, and now watch huge boulders burying the dead for good. It was all filmed, and post-produced, long before Israel commenced its present slaughter in the Gaza Strip. Yet it comes out - now, and audiences will no doubt find the resonances uncomfortable.

The Fremen are quite obviously based on the nomadic Arab tribes made famous by TE Lawrence, whose memoir of the Arab revolt so inspired Frank Herbert’s original novel. Their language is clearly inspired by Arabic; their messianic figure is called, among other things, the mahdi - a term with a long history in Islam, perhaps best known in the predictions by some Shia that the 12th imam, Muhammad al-Mahdi, will return from his mysterious occlusion to lead the faithful in their final victory.

The rules of the Hollywood epic complicate this analogy. After all, things have only come to this pass because the Fremen have become such an irrepressible nuisance to the occupiers. Their daring raids on the resource-extraction operations of the colonisers have taken up much of the screen time so far - and director Denis Villeneuve has made an altogether poetic job of it. There is nobody in the world who can do such a great job of presenting incomprehensibly vast objects moving very slowly - a skill that transfers with great facility to the related task of showing incomprehensibly vast objects exploding.

Villeneuve’s drift towards the Hollywood mainstream has led some critics to become sniffy about him - notably AS Hamrah, a fine writer of legendary curmudgeonliness. I confess, on the contrary, to being a great admirer of his films and, much of the pleasure of both Dune films thus far comes, for me, from the joy in seeing his particular directorial eye cast on a filmic project large enough in scale to truly stretch it. I first fell in love with his work with Arrival (2017) - a more philosophical science-fiction vehicle, whose plot turns on recherché theories of language; already by that point his art was fully formed. There were the patient, odd shots of tall, cigar-shaped UFOs floating over the landscape; the weepy melodrama of the characters; the post-classical soundtrack, in that film by the late genius, Jóhann Jóhannsson, full of strange vocal cues; and the bassy stings that are now officially known by the onomatopoeic term of art, ‘braam’.

Messiah

For those unfamiliar with the Dune universe, some exposition is necessary. It takes place many thousands of years into the future: humanity has colonised thousands of planets in the known universe, governed as an ‘imperium’ with a kind of feudal structure. Transit between star systems depends on the guidance of a specialised cast of navigators, who can only do the job by consuming a hallucinogenic fungus called melange or spice, which grows only on a single planet - the perilous desert world of Arrakis. As the saga opens, this planet is reassigned from the suzerainty of the fascistic Harkonnen house (the aforementioned pale and hairless ones) to that of the do-gooder, Atreides, and our hero (sort of) is Paul Atreides, heir of the reigning duke, Leto.

Apart from the imperial forces, the only inhabitants of Arrakis, the Fremen, who live deep in the desert, are exposed permanently and healthily to the spice, and coexist respectfully with the terrifying sandworms - huge monsters attracted by rhythmic sound … like the sound of spice extraction machines, for instance. They are not exactly noble savages - they are masters of technologies relevant to their survival and communal life. But they are not romantic about their lives, and look forward to an eschatological event that will bring abundant water to Arrakis and make the desert bloom.

To this end, the Fremen await the coming of a messiah - the ‘Lisan al-Gaib’. But we filmgoers know (and a few Fremen suspect) that this expectation is cultivated among them by an imperial religious order of women, the ‘Bene Gesserit’, whose true mission is a kind of eugenic singularity in the imperial metropole. They see the Fremen as future shock troops for the messiah figure they themselves are trying to breed in due course. Needless to say, the best laid plans of mice and nuns go awry. Leto Atreides’s plan to cultivate an alliance with the Fremen is cut short by his death, thanks to the treachery of the emperor; Paul survives, ‘goes native’ with his doubtfully sane mother, and struggles with the decision to proclaim himself the ‘lisan al-Ghaib’.

Herbert was a true liberal of his own day - disgusted with imperialism, but disquieted by the fanaticism of those who fought against it. Villeneuve, a liberal of ours, heightens things in both directions. The female characters get more of a look-in in his version, but not in a way likely to cheer Hillary Clinton-type corporate feminists. The relentless competence of Paul’s mother, Jessica, may have had that effect in the first movie; but she spends much of this one communing with her unborn daughter and conspiring at a galactic holy war. She is Paul’s great temptation: against her is arrayed his Fremen girlfriend, Chani, whose progressive alienation from him marks the distance between his own aims and the apparent wellbeing of her people.

In Villeneuve’s version, Paul is pushed over the edge of his initial idealism to become that worst of things for modern Hollywood liberals - some kind of populist, who offers his people blood, sweat and tears, but never enough to sate them. He does so in the face of grotesque and genocidal oppression, and it is to the film’s credit that we both root for him all the way along and grow nauseous at what it all means.

Mass production

All of which makes this a somewhat peculiar blockbuster. There is no real doubt about its credentials on that score: it was made for a little under $200 million, and has made a little over $500 million, as I write, with a good stretch to go in cinemas yet (big money in; big money out). As with all such projects nowadays, it is based on pre-existing, bankable intellectual property. The cast - Timothée Chalamet, Josh Brolin, Rebecca Ferguson, and so forth - are recognisable enough, but not likely to overshadow the material, as one of the few remaining old-fashioned stars like Tom Cruise might. On paper, it looks a very modern blockbuster indeed, after the fashion of the Marvel movies and whatever else.

The end product, however, is quite different. Probably not since Christopher Nolan’s Batman trilogy has a big-name IP movie series had such a clear directorial stamp on it (I suppose we can throw Zack Snyder in there too, since his sophomoric self-seriousness is readily recognisable, whatever else may be said about it). It slips occasionally - the near-monochrome sequence on the Harkonnen home world is, alas, a little Snyder-esque. Yet the virtues of the Dune movies - their patience, their intelligent and judicious use of source material, their distinct visual style, their emotional directness, their queasy moral ambiguity - are the virtues above all of their director. Auteur theory is back!

Or is it? One swallow (or two, I suppose) does not make a summer. It is quite conceivable that this is a mere clerical error: the money-men - in this case the notoriously bloodless philistine, David Zaslav of Warner Bros - handed an internet protocol long known to be cursed for Hollywood purposes (rather like Don Quixote) to Villeneuve, and the first movie benefited from the distorting effects of the Covid pandemic on the film industry; therefore they couldn’t not make the second one.

It could still be a straw in the wind, however. The dominant franchises of the last decade are clearly in crisis; the once-imperturbable Marvel brand now produces turkey after turkey, most obviously, and it is not clear what blood is left to get out of the Star wars stone. Meanwhile, the second Dune is doing brisk business; and the two tentpole movies of last year, Barbie and Oppenheimer, clearly fit into certain well-storied commercial film stereotypes (feature-length toy advert, and Oscar-bait biopic, respectively), but were both equally director-led projects from the artistically respectable Greta Gerwig and Nolan.

Could the return of the auteur be the solution to Hollywood’s general aesthetic exhaustion? Perhaps. The picture is not uniformly promising. Notably Marvel’s one serious attempt to do an auteur movie, Eternals, was a disastrous flop, with sequels now officially abandoned - the studio apparently repents of taking too many risks (sic!). That is the problem with leaning into the cult of the heroic artist: it is an inherently unpredictable way to make a buck, which is precisely how we ended up with the perfectly oiled Marvel machine, with its house anti-style and its literal five-year plans in the first place.

The wider economic picture is not great for movie-going either - perhaps the whole thing will finally be swallowed whole by Netflix and friends (as per the title of Hamrah’s recent review collection, The earth dies streaming). It is the streaming giants who have the most efficient machine for turning data-science on audience tastes into industrially extruded content. Whether or not the recent commercial success of certain auteurs represents a turn in Hollywood’s paradigm of production, it at least indicates that mass audiences deserve to be treated with more dignity than they recently have been. But the tyranny of money men like Zaslav and Bob Iger of Disney remains an obstacle to a true revival in quality mass-market cinema.