15.02.2024

World without colonisation

Chris Gray reviews Robbie McVeigh and Bill Rolston Ireland, colonialism and the unfinished revolution Chicago 2023, pp480, £19.99

In 1966 a book by a journalist called Colin MacInnes was published in the UK. This book, entitled England, half English, registered, so to speak, the arrival of numbers of immigrant families that made a distinctive contribution to the national scene.

MacInnes apologised, in this context, “for using the odious word ‘half-caste’ to describe the English children of Africans or West Indians and of our women” (p32, his emphasis). As he puts it eloquently,

These boys and girls - thousands of them have now been born and bred among us - are, and feel themselves to be, as ‘English’ as anyone is. They represent (together with the children of other immigrant groups of the 1940s and 1950s - chiefly Poles, Cypriots, Maltese and Pakistanis) the New English of the last half of our century: the modern infusion of that new blood which, according to our history books, has perpetually recreated England in the past and is the very reason for her mongrel glory [sic]” (England, half English pp32-33).

This means, he notes, that “A coloured population - and this means a growing half-caste population - is now a stable element in British social life” (p24).

Our authors focus on this interbreeding, using the Latin American term, mestizaje (the half-caste condition, life as a mestizo) and show that it applies to Ireland:

Irish history is a definitive example of mestizaje. This is patently obvious in the north, where a unionist prime minister can have a Gaelic family name [Terence O’Neill], while the founder and leader of the Social Democratic and Labour Party [John Hume] that of Scots Planters (Ireland, colonialism and the unfinished revolution p26).

They ask us to imagine a world without colonisation:

What appears little more than an abstract fantasy in our contemporary postcolonial world was ‘pre-contact’ recently in the history of humanity. Most of us - peoples, cultures and continents - were ‘uncolonised’ before the ‘age of discovery’ ... Thus, the future must be faced from the perspective of the decolonised rather than the uncolonised. Crucially this means that the whole world is characterised by mestizaje … [which] frames the challenge for contemporary anti-imperialism: what is to be done? (pp65-66).

This state of affairs relates to the last century’s determining conflict, World War I. McVeigh and Rolston write:

It bears emphasis that this conflict was definitively an imperial choice rather than a democratic one … The human cost was, however, enormous - with over one million military deaths across the armies of the British empire alone and an additional two million wounded. Lenin made sense of this dynamic in his Imperialism: the highest stage of capitalism. He argued that the Great War was “an annexationist, predatory, plunderous war among empires” (p53).

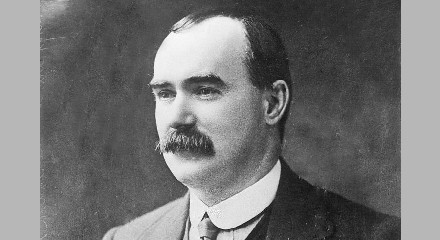

World War I led to the Irish war of independence (aka the Sinn Féin rebellion) and the partition of Ireland. I find it difficult to resist the conclusion that partition has been a disaster, wherever it has been imposed. Our authors reproduce James Connolly’s prescient remarks on Ireland’s case:

The partition of Ireland would mean a carnival of reaction both north and south, would set back the wheels of progress, would destroy the oncoming unity of the Irish labour movement and paralyse all advanced movements while it endured” (p135).

Two states

As McVeigh and Rolston point out, the legislative means used by the British state was the Government of Ireland Act 1920, which created two states on the island: Northern Ireland continued to be framed by the 1920 act, while the 26 remaining counties acquired further autonomy following the treaty which came into force in 1922:

Now styled a ‘free state’, it became a white dominion of the British empire - like Australia, Canada and South Africa. Despite this enhanced autonomy, however, it was a far remove from the republic proclaimed in 1916 and endorsed by the Irish electorate in 1918. Northern Ireland was, of course, left even more unambiguously locked within a colonial context - still in the double bind of union and empire (p138).

When the southern taoiseach, Seamus Costello, announced that the free state was to call itself the “Irish Republic” in 1948, which led to the (26-county) Republic of Ireland Act, the UK government under Clement Attlee accepted this fait accompli, but replied with the Ireland Act 1949, which ruled that Ireland would not be treated as a foreign country for the purposes of British law.

Furthermore this act effectively reinforced partition, since it declared that Northern Ireland would continue to remain part of the United Kingdom and of the British Commonwealth (successor to the empire), unless the parliament of Northern Ireland decided otherwise. The working party report declared that “it [had] become a matter of first-class strategic importance ... that the north should continue to form part of His Majesty’s dominions” (quoted p168). Not surprisingly, Dáil members expressed their displeasure over this.

The question now is: how much has the situation changed following the 1998 Good Friday Agreement? The GFA entailed abandoning the constitutional claim to sovereignty over the whole island, as expressed in the southern constitution. This means that the 26-county state is now a junior partner in the management of continuing conflict in the north, alongside the UK.

Moreover, despite the lurching of the post-GFA state from crisis to crisis, no-one nowadays in the political establishment of the 26 counties is suggesting that the reunification of the national territory ‘could provide the only permanent solution to the problem’ (pp186-87).

McVeigh and Rolston see the hand of the European Union in the GFA: “On June 11 2004 the referendum was held [in the south] on the proposal to remove the constitutional entitlement to citizenship by birth”, confining that right to individuals having “at least one parent who is an Irish citizen”:

This change was supported by the two Irish government parties, Fianna Fáil and the Progressive Democrats - as well as Fine Gael, the largest opposition party. It was opposed by the Irish Labour Party, Sinn Féin and the Green Party. In the event, voters elected to change the jus soli basis of Irish citizenship. On a turnout of 59.9% of the electorate, 79.2% voted ‘yes’ and 20.8% voted ‘no’.

In effect, therefore, Irish citizenship law had become completely determined by the implications that it was deemed to have for EU citizenship. The outcome … was potentially a ‘problem’ for the UK and the EU, but not for the Irish state. Yet changes driven through by the Irish government and almost completely justified in terms of concerns about the ‘abuse’ of EU citizenship had profound implications both for the GFA and Irish citizenship and nationality.

This supine acceptance of the logic of being ‘Good Europeans’ had a clear racial undertow. For all the government disclaimers, the population was quite clear that the referendum was about race and migration. The RTE exit poll following the referendum made clear the “spontaneous reasons for voting yes”: “Country being exploited by immigrants” - 36%; “Too many immigrants” - 27%; “Being in line with other EU countries” - 20%; “Children should not be automatically Irish citizens” - 14%. Aggregating the first, second and fourth of these, we can suggest that the insistence that the referendum had “nothing to do with racism or immigration” [comment by Mary Hanafin, FF chief whip - see p195] rang more than a little hollow (pp195-96 - see also references to the ‘Chen case’, pp191-97).

Six Counties

Having brought readers up to date with 26-county developments, our authors then give a summary of political history to date in the Six Counties. With the northern political establishment having asked in 1922 to opt out of the newly established Irish Free State by petitioning King George V to that effect (as they were entitled to do under Article 12 of the Anglo-Irish Treaty), administration of the Six Counties was duly handed over to the Ulster Unionists. Once this had happened, as the authors say, “the issue of Northern Ireland [and indeed Six County matters in general] was barely discussed in Westminster for the next half century” (p234). For example, the 1967 Abortion Act specifically stated that its provisions did not apply to Northern Ireland.

However, convulsions within the Six Counties from 1964 to 1970 and beyond brought ‘direct rule’ into play. As a result, partition, as the last significant act of colonisation in Ireland, is still alive and well: “The state formations on the island remain those framed by the Government of Ireland Act 1920. Moreover, the artificial border that separates them threatens to become more contested, more militarised by Brexit” (pp390-91). Ending partition means the dismantling of the two partitionist states. “In this phase of decolonisation, this is the target: everything else is tactical or strategic in relation to this goal” (p403).

The situation is all the more anomalous, given the decision that Northern Ireland should cover only six Ulster counties. The reasons for this are well known, but our authors usefully underline the precise nature of the problem unionists faced: viz. the need for the area under their control not to be too small as to be unviable, yet not too large to prevent their controlling it effectively.

McVeigh and Rolston allude in one passage to the notorious ‘two nations theory’, writing:

… arguably the state had to make people Protestant. Certainly, it had to create a context in which the categories, ‘Protestant’ and ‘Catholic’, were principal determinants of identity within the state.

This is not as silly as it sounds. In 1920, Protestants were Irish. The Unionist Party and the Orange Order were both Irish. Even in more formal religion terms, the term ‘Protestant’ was less than precise in 1920 ...

In other words, while the term ‘Protestant’ became an ethnic label with real and immediate meaning in the context of the Northern Ireland state, it was never a simple reflection of religious, political or cultural identity. The new state made people ‘Protestant’ in an entirely new way. In this sense, the closest parallel is with the function of ‘whiteness’ in apartheid South Africa: in both cases unifying identities were constructed in novel form in order to transcend all the tensions and contradictions within the settler polity.

Thus, while Northern Ireland never succeeded in achieving dominion status within the empire, here was what Protestant dominion looked like (pp209-10).

The authors deserve praise for mentioning the important figure of Aimé Césaire, poet and politician of the island of Martinique, who pointed out the parallel between fascism in Europe and the practices of colonial administrations outside that continent. They quote from an article by Vijay Prashad, which says of Césaire:

He wanted to judge colonialism from the ashes of Nazism - an ideology that surprised the innocent in Europe, but had been fostered slowly in Europe’s colonial experience. After all, the instruments of Nazism - racial superiority, as well as brutal, genocidal violence - had been cultivated in the colonial worlds of Africa, Asia and Latin America. Césaire, the effervescent poet and communist, had no problem with the encounter between cultures. The entanglements of Europe’s culture with that of Africa and Asia had forged the best of human history across the Mediterranean Sea. But colonialism was not cultural contact. It was brutality (p324 - see also the bibliography, p433).

Brexit, as the authors point out, has not changed fundamentals - only intensified them. The border is still a bone of contention: should it be the Irish Sea, or “the incongruous and illogical international boundary meandering between Newry and Derry and Dundalk and Bundoran - separating people and communities for no good reason”? (p283).

A few minor quibbles:

1. The important figure of Walter Rodney (1942-80), Guyanese author of How Europe underdeveloped Africa, could have been mentioned.

2. More could have been said about the ‘two nations theory’, as it still has its supporters today.

3. Brexit is not just a project of excluding people of colour, but also an attack on the social democratic tradition of the EU - as exemplified by the one-time commission president, Jacques Delors.

In conclusion, the analysis offered by Robbie McVeigh and Bill Rolston would appear to reinforce the political conclusions drawn in the CPGB Draft programme. Personally, I think that is a plus.