04.01.2024

Record-breaking in the wrong way

Storms, floods, drought and fire on an almost biblical scale presage social breakdown. It is socialism or barbarism, says Eddie Ford

Globally we had record temperatures, sizzling heatwaves, devastating floods, wildfires, fierce storms, and all manner of other extreme weather events in 2023 - with no signs of letting up.

Just over the past few days Storm Henk has battered the UK with over 300 flood warnings after large parts of England and Wales saw strong winds and heavy rain leading to flooding, travel disruption and power outages. The strongest gust of wind recorded on land was 81mph at Exeter airport in Devon. Nearly a week earlier, a small tornado tore through Greater Manchester during Storm Gerrit, leading to three fatalities after a car became submerged in the River Esk amid ferocious weather and severe flooding. Though it would be a mistake to Cassandra-like ascribe every weather event to human-induced global warming, it is hard not to see the impact of climate change on the frequency of storms. We know that increased sea surface temperatures warm the air above and make more energy available to drive hurricanes, cyclones and typhoons. As a result, they are likely to be more intense and come with extreme rainfall.

All this followed the not particularly surprising news that the UK had its second-hottest year on record in 2023, according to provisional data from the Met Office - the average temperature at 9.97°C was marginally lower than the 10.03°C recorded in the previous year. Such a warm year, they say, would have occurred only “once in 500 years” without global warming. The heat peaked in June and September, both record hot months in a series dating back to 1884, and the UK’s 10 warmest years have all occurred since 2003. In today’s overheated climate, the Met Office reckons that such warm years are to be expected every three years.

Ever higher

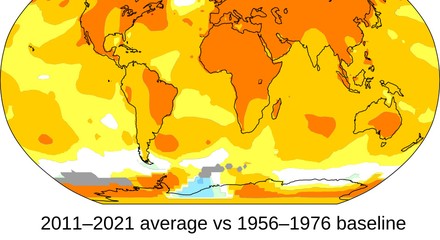

But it is the same pattern throughout the world. As widely chronicled, including in these pages, the world experienced the highest mean temperature on record for the first 11 months of 2023 at 1.46°C above the pre-industrial average. Hence, from January to November, the average was 0.13°C higher than 2016, which was previously the warmest calendar year on record.

Now, some of this can be attributed to the El Niño event which arrived in June. A totally natural phenomenon, of course, it emerges from the central and eastern Pacific near the equator, and is responsible for the warming and cooling of large areas of the ocean - which significantly influences changes in global temperature and where and how much it rains. The outcome being six record-breaking months and two record-breaking seasons in the northern hemisphere.

Thus June, July and August brought the hottest summer by a large margin, with a global average of 16.77°C, a 0.66°C rise. While September, October and November made for the warmest autumn with an average temperature of 15.30°C, which was 0.88°C higher than the previous average. As for July, globally it was the hottest month ever recorded, also by a large margin, at 16.95°C - beating the previous record set in July 2019 by 0.33°C. But just be glad you were not living in Phoenix, Arizona, that saw a life-sucking 31 days of temperatures reaching 43°C or higher between June 30 to July 30, surpassing by two days the 2020 record.

China had its own extreme weather last year, of course. In late July and into early August, typhoon Doksuri unleashed 744.8mm of rainfall at a reservoir on the outskirts of Beijing, the highest since 1891. In the US, pre-existing drought conditions and winds from hurricane Dora resulted in the deadliest wildfire for more than 100 years - at least a hundred died, with many thousands evacuated and over 2,000 structures destroyed. And in late August to early September, wildfires in northern Greece became the largest ever in the European Union, with 93,000 hectares burnt. And on, and on, and on. Not for nothing did the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration calculate in mid-December that there was a “greater than 99% chance” that 2023 would turn out to be the hottest year in its 174-year dataset.

Ominously, the pattern outlined above looks set to continue, if November was anything to go by - being the warmest November ever recorded. On November 17 and 18, the earth’s global average surface temperature was more than 2°C higher than pre-industrial levels - the first time scientists have ever recorded such a reading. Given that the El Niño effect is set to reach its full strength in the northern hemisphere this winter, more extreme weather events are likely to be unleashed in 2024.

Warming oceans

Out of all these statistics, perhaps most disturbing of all was the sharp increase in sea surface temperatures, which have been abrupt even for an El Niño year. Climate scientists do not yet fully understand why the ocean heat increase has been so dramatic, nor what the consequences will be for the future. First signs of a state shift? A freak outlier? Indeed, ocean temperatures began reaching new highs long before El Niño kicked in.

But whatever the exact reasons, from late March through to October the world’s average sea surface temperature consistently broke daily records. By July, these temperatures were nearly 1°C above average, as marine heat waves racked nearly half of the globe’s oceans, and the European Union-funded Copernicus Climate Change Service - using billions of measurements from satellites, ships, aircraft and weather stations around the world - found that October marked the sixth consecutive month that Antarctic sea ice was at record lows for the time of year at 11% below average.

In fact, western Antarctica was affected by several winter heatwaves associated with the landfall of atmospheric rivers. In early July, a Chilean team on King George Island, at the northern tip of the Antarctic peninsula, registered an unprecedented event of rainfall in the middle of the austral winter when only snowfalls are expected. In January, a massive iceberg, measuring about 1,500 square kilometres, broke off from the Brunt ice shelf in the Weddell Sea. It was the third colossal calving in the same region in three years. Sea surface temperatures hit an average of 20.79°C, the highest on record for October, and Europe saw above-average rainfall - notably in Storm Babet, which hit northern Europe, and Storm Aline, which impacted on Portugal and Spain, bringing heavy downpours and flooding. It almost goes without saying that such warm waters are unprecedented in modern records - maybe even for the last 125,000 years. Ocean life suffered, naturally, as the relentless accumulation of all that heat took its toll. Coral reefs suffered widespread bleaching across the Gulf of Mexico, the northern Atlantic, the Caribbean and the eastern Pacific.

Looking at all this, James Hansen - director of the climate programme at Columbia University’s Earth Institute and whose 1988 testimony to the US Senate is widely regarded as the first high-profile revelation of global heating - has warned that the world was moving towards a “new climate frontier” with temperatures higher than at any point over the past million years. He is far from alone in having such fears. Five years earlier, the authors of the ‘Hothouse earth’ paper envisioned a domino-like cascade of melting ice, warming seas and dying forests, which could tilt the planet into a state beyond which human efforts to reduce emissions will be increasingly futile. As we look at the dramatic rise in sea surface temperatures last year, this seems more and more of a possibility.

James Hansen has said the best hope is for a “generational shift” of leadership, which shows, of course, that while he is doubtless an outstanding climate scientist, he simply does not get social science. The climate crisis can be summed-up in four short words: it’s the economy, stupid.

Obviously that is not a message that those who attend the annual Cop jamborees want to hear. Instead they use these vast conferences to virtue signal and haggle over resolutions that have absolutely no effect in the real world. Cop28, held in Expo City, Dubai, last year, was par for the course. Over 70,000 people given accreditation for the event, with 400,000 more granted access to the surrounding “blue zone”. The whole thing is said to have had the largest carbon footprint of any climate summit - very many using private jets to swan in and swan out.

Fitting

Putting Sultan Al Jaber in charge of the proceedings could not have been more fitting - he is CEO of the Abu Dhabi National Oil Company and we all know what he really thinks. Before the conference had even begun he was complaining that there was “no science” behind fossil fuel being phased-out and achieving the target of limiting the global temperature rise to 1.5°C as set out in the 2015 Paris Accords. Indeed there were plenty of stories doing the rounds that the UAE used the conference to strike new oil and gas deals. Still, what did you expect?

So what was achieved? For years, the Cop negotiations had been bogged down in arguments about whether to call for a “phase out” or “phase down” of fossil fuels - countries such as Russia, Saudi Arabia and China rejecting the ‘phase out’ formulation, instead they want ‘phase down’. And praise be to god, Al Jaber was able to proudly announce that a final compromise agreement had been reached.

The joint resolution now says “transition away” from carbon energy sources. Naturally, this is going to be done “in a just, orderly and equitable manner” to “mitigate” the worst effects of climate change, and net zero will be magically reached by 2050. But it won’t. On present trends the world is set to exceed the 1.5°C limit very soon and then hurtle towards 2°C and doubtless beyond. What that means for 2050, 2070, 2100 is extraordinarily difficult to tell in climate terms. Socially, however, the danger is clear - descent into some kind of barbarism.

Civilisation still might be saved, however, but it can only be saved through the working class organising into a party and taking power at a global level. There can be no local or national solutions. Protest politics are clearly inadequate. It really is a case of socialism or barbarism.