20.07.2023

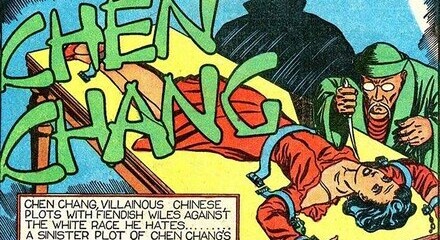

Cross-party yellow peril

Parliament’s Intelligence and Security Committee has produced a lurid account of the challenge represented by China. Mike Macnair argues that the UK is playing catch-up with the US hegemon

In 1903, 120 years ago, Erskine Childers’ best-selling The riddle of the sands was published. The book told a story of holiday-making British yachtsmen uncovering a secret German plot to invade Britain across the North Sea, using a fleet of tugs and barges based in the East Frisian Islands. The plot is fantastical: Germany invading Britain with tug-drawn barges across 370 miles of the North Sea is a lot less militarily plausible than the unworkable 1940 plan, ‘Operation Sea Lion’ (to have been launched from Normandy); or than the ‘French invasion scare’ of 1859-60; or William Le Queux’s 1894 French invasion book, The great war in England in 1897.

Nonetheless, The riddle of the sands dramatised for the British public the ‘German threat’ to Britain. This threat was actually not a threat of German invasion of Britain, but rather of German competition in arms markets and capital goods markets, and in geopolitics for influence in Latin America and the Ottoman empire, as well as for colonial possessions in Africa and China - reflected also in German naval expansion. And reflected, too, in unwelcome ‘interference’ like supplying arms and partial diplomatic backing to the Transvaal and Orange Free State before their conquest by the British 1899-1902 South African War (in which Childers fought). The ‘German threat’, as dramatised by Childers’ novel, supported political backing for British arms-budget expansion and for the reversal of British alliances, symbolised by the 1904 Entente Cordiale with France. The book was thus a landmark on the road to 1914.

In the 21st century there are too many thrillers and alternate-history fantasies out there for the open production of fiction to have this sort of political influence. The fantasies produced to cover real commercial and geopolitical motives instead take the form of official announcements and ‘intelligence reports’, like the case made in 2002-03 for the Iraqi Ba’athist regime’s ‘weapons of mass destruction’ (WMD) or the story of ‘Russian interference’ in the 2016 US presidential elections.

China report

The latest fantasy of this type is the report on China by parliament’s Intelligence and Security Committee - a joint committee of nine members of both houses, though some have changed during the production of the report: actually listed are 11 MPs (six Tory, three Labour, two Scottish National Party) plus one peer - former ‘First Sea Lord’ Lord West of Spithead. The report was laid before parliament on July 13.1 The government promptly responded, with prime minister Rishi Sunak issuing a written statement about what the government is doing about the ‘China threat’ on the same day.2

The ISC would be a classic case of ‘regulatory capture’, but for the fact that it is plainly designed to give the appearance of regulatory oversight, while in fact being controlled by insiders. Its members have to be ‘cleared’ to see classified information, and eight out of the 12 are either former military or security, or have held ministerial or shadow responsibilities in these fields. The exceptions are the two SNP MPs, Diana Johnson (a shadow junior minister shadowing the Foreign and Commonwealth Office in 2016, resigning in the coup attempt against Corbyn that year, and vice-chair of Labour Friends of Israel) and Jeremy Wright, who as attorney-general in 2014-18 will also have been security-cleared. The effect is not political oversight over the security apparat, but a parliamentary lobby group for the security apparat pressing for increased legal powers and increased resources for this sub-group of the state bureaucracy.

The report they have published is massively redacted, sometimes in places where it seems a real stretch for whatever is omitted to be classified. Readers are, in effect, asked to give personal trust to the members of the ISC, on the basis that we are not allowed to know what the actual grounds of their opinions are. If these are anything like the Iraq WMD dossier or the ‘Russian interference in the US elections’ story, when they are finally released they will turn out to be unsupported speculations and products of superficial web-browsing.

A Chinese invasion of Britain is a lot less easy to imagine than a French or German invasion in the late 19th or early 20th century, or even a Soviet invasion in the cold war period. In Frederik Pohl’s humorous Black star rising (1985), the late 21st century former USA is ruled by a still-Maoist China, when space aliens arrive. In David Wingrove’s dark (and sprawling) 1988-99 Chung Kuo series (an even longer rewrite has been in progress since 2017) a Han-derived culture rules a 200-year future world. In both cases Chinese rule is preceded by internally driven ‘western’ collapse. The same is reportedly true of Song Han’s 2066: red star over America (2000), which is untranslated.3

In place of an invasion fantasy, we get a subversion fantasy. This has a superficial appearance somewhat similar to cold war subversion fantasies;4 but the underlying geopolitics is profoundly different. We are headed not for a 25-year period of ‘containment’, with only in the long term a new turn to ‘roll-back’ à la Carter and Reagan (and since). The US agenda - once the proxy war of conquest of Russia has issued in a ‘colour revolution’ and a new Yeltsin, and Russia has been disarmed, de-industrialised and Balkanised - is an analogous war of conquest leading to China being partitioned, disarmed and de-industrialised. This may imply a new 1914 (but this time with nukes); in any case, not a new cold war.

The report tells us that China threatens us with economic power and political influence. Thus:

China is engaged in a battle for technological supremacy with the west - one which it appears to be winning. China’s ‘Made in China 2025’ strategy is an initiative designed to help China become a manufacturing superpower through investing in, and then leveraging, foreign industries and foreign industry expertise in order to help China master complex design and manufacturing processes more quickly. China targets other countries’ technology, Intellectual Property (IP) and data in order to “bypass costly and time-consuming research, development and training”. This approach means it can exploit foreign expertise, gaining economic and technological advantages and thereby achieving prosperity and growth more quickly - and at the expense of others (p21).

And:

China’s ruthless targeting is not just economic: it is similarly aggressive in its interference activities, which it operates to advance its own interests, values and narrative at the expense of those of the west. While seeking to exert influence is a legitimate course of action, China oversteps the boundary, and crosses the line into interference in the pursuit of its interests and values at the expense of those of the UK (p3).

So ‘influence’ crosses into ‘interference’ when it is “at the expense of” the “interests and values” of the UK.

What are these “interests and values”? Evidence to the committee from one of the bits of the ‘security community’ identifies these:

If you think of UK interests as being in favour of good governance and transparency and good economic management, which I think is fair, we regard those as things which are good in their own right, but also serve our national interest, because it helps with trade, investment, prosperity and stability and so forth, then I think that China represents a risk on a pretty wide scale (p15).

The claim that the UK has an interest in “good governance” is pretty laughable after the last few years of the chaotic Conservative administration. The claim that it has an interest in “transparency” is equally indefensible, in the light of the role of the City of London as organiser of the world’s main network of offshore operations, the continued use of dodgy interlocutory injunctions on privacy and commercial confidentiality grounds, and so on. “Good economic management,” coming from a UK government agency, plainly means no more than primacy of the financial sector and compliance with International Monetary Fund ‘restructuring’ programmes, up to and including Yeltsin-style de-industrialisation.

China allegedly threatens these “interests and values”, according to the report, firstly, because

China wants to be a technological and economic superpower, with other countries reliant on its goodwill - that is its primary measure of sovereign success. MI5 observed:

*** [redacted text] it is going after IP [Intellectual Property], it is building itself as a power, it is positioning China in the world at the top of the tree (p11).

Secondly, it is doing so because “China is building global military capabilities to rival the US by 2049” (p12).

What this amounts to is a claim that China is a threat to the UK if it does not accept a fully-subordinate position in the world order. I have written about this issue before, in relation to the US government’s conceptions of grand strategy. The ISC report transposes into “UK interests” what are, in reality, US interests in preventing the emergence of a ‘peer rival’.5

The report goes on to provide an analysis of how China ‘interferes’ against UK interests:

In terms of cultivating influence, [the government] told us that the [Chinese intelligence services] use the following methods:

- covert support for foreign political parties;

- covert funding and support of groups favourable to the [Chinese Communist Party];

- using trade negotiations or investment activities as a platform to influence key decision-makers through bribery and corruption;

- co-opting academics, think-tank employees, former officials and former military figures;

- using cultural and friendship institutions to access key thinkers and decision-makers;

- obtaining and releasing materials to discredit individuals opposed to China’s views;

- funding of universities, both to influence research direction towards Chinese priorities and to gain access to prominent individuals through philanthropy; and

- covert media manipulation to undermine support for policies and views deemed harmful to China (p20).

These are, of course, merely the methods which the CIA and other ‘western’ security apparatuses routinely use in ‘third world’ countries and have, indeed, also used in Europe. The problem is that we do not want such methods used against us (except by the USA …!).

Case studies

Within its general framework, the second half of the ISC report provides us with a series of ‘case studies’. Universities (pp103-21) are claimed to be ‘soft targets’, needing considerable ‘toughening’ - not only by section 9 the Higher Education (Freedom of Speech) Act, which is targeted against China (universities may not permit overseas funders to limit freedom of speech, but the minister may exempt, for example, US funders), but also by substantial expansions of security service control over collaborative research projects which might have military uses or might involve the UK losing technological advantages, and by positive vetting of researchers.

A similar “Case study: industry and technology” (pp123-49) is considerably vaguer. But the general issues are helpfully discussed:

The Communist Party of China (CCP) deems both economic well-being and technological advancement as essential to its national security and maintaining power, and to mitigate perceived threats from the west … China’s overall aims are to gain technological parity with the west, and eventually to surpass them, in a process it identifies as ‘national rejuvenation’ (quote from government evidence, p123); and

Success will enable China to project its economic, military and political power globally, as steam and computing did for Britain and the US respectively in the 19th and 20th centuries (quote from National Cyber-Security Centre evidence, p123); and

As an advanced and open economy, the UK is a clear target for China. The UK has a reputation for being open to foreign investment, and China invests in the UK more than in any other European state. Foreign direct investment [FDI] into the UK from China between 2000 and 2017 was approximately £37 billion (with the next largest recipient of Chinese investment being Germany, at £18 billion) (p125).

Chinese FDI in the UK may be merely a means of acquiring technical advantages (pp129-30). And - shock, horror! - the Chinese are engaged in pursuing their state interests through diplomacy in international standards-setting bodies (pp132-33), so that

Without swift and decisive action, we are on a trajectory for the nightmare scenario where China steals blueprints, sets standards and builds products, exerting political and economic influence at every step. Such prevalence in every part of the supply chain will mean that, in the export of its goods or services, China will have a pliable vehicle through which it can also export its values. This presents a serious commercial challenge, but also has the potential to pose an existential threat to liberal democratic systems (p134).

A similar analysis is applied to the special case of Chinese willingness to build nuclear reactors for the UK, with the additional fear that this allows the Chinese to obtain control of ‘critical infrastructure’ (pp151-80). All this stuff is no more than fairly naked protectionism in the style of Joe Chamberlain and his followers in the late 19th to early 20th century.

The last section of the report is an ‘Annex’ on “Covid-19” (pp181-91). This merely recycles the combination of real information about the Chinese government’s initial attempts to cover up the bad news about the outbreak with the various free-floating speculation about the virus possibly being a laboratory product; so it is just a form of dog-whistle China-phobia production.

A constantly recurring theme of the report is Chinese “theft” of “intellectual property”. I have written about this issue at length in the past,6 and do not propose to repeat much of what I have said there. “Intellectual property rights” are merely statutory monopolies. The point was elaborately made from a leftwing point of view in Michael Perelman’s 2002 book Steal this idea, which I reviewed in 2003; and from a rightwing free-market point of view in N Stephan Kinsella’s 2001 article, ‘Against intellectual property’,7 and Michele Boldrin’s 2010 book, Against intellectual monopoly.

As several authors have pointed out, the USA in the period of its industrial rise took the same attitude to “intellectual property” that the Chinese have more recently. It is with the US’s move into relative decline in productive industry that increased dependence on “technical rents” has carried with it an increasingly ferocious promotion of “intellectual property”. The UK is in a much more advanced state of decline than the US, so that it is unsurprising that the ISC should be so heavily concerned to protect anti-competitive rentier interests. Indeed, the report recognises that in some respects China may be ahead, so that “intellectual property theft” would be useless to them:

HMG cites artificial intelligence (AI) as an area where increasing Chinese dominance is causing concern, since, if China becomes the market leader, western countries might have to accept the rules and regulations that China attaches to the technology and Chinese standards on AI applications … (p125).

Solutions

The report has an overall tone of criticising the UK government for being late to identify the Chinese ‘threat’ and not doing enough to address it. The solutions it proposes are partly drawn from US practice, and partly would increase the power of the securocrats. Thus

The government’s lack of understanding contrasts with the approach of the US, which has already produced a national strategy on critical and emerging technologies, aimed at protecting its technological dominance, in which it lists what it considers to be its 20 priority technologies (p4).

And the report identifies serious concerns about economic decision-making and existing Chinese political influence:

If the government is serious about tackling the threat from China, then it needs to ensure that it has its house in order, such that security concerns are not constantly trumped by economic interest. Our predecessor committee sounded the alarm, in relation to Russia, that oligarchs are now so embedded in society that too many politicians cannot even take a decision on an investment case because they have taken money from those concerned. We know that China invests in political influence, and we question whether - with high-profile cases such as David Cameron (UK-China Fund), Sir Danny Alexander (Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank), Lord Heseltine (The 48 Group Club) and HMG’s former chief information officer, John Suffolk (Huawei) - a similar situation might be arising in relation to China (p4).

The UK should copy the US in requiring ‘foreign agent registration’ and in addition should criminalise ‘economic espionage’:

In evidence to this inquiry, the intelligence community told the committee that legislative change is even more necessary in relation to China. MI5 told us that “a Foreign Agent Registration [Act]-type power, which the Australians and Americans enjoy, ... [would] have proportionately more effect against ... Chinese activity”. A key issue of concern is the theft of non-classified information, which can be difficult to grip because a significant amount of the activity does not currently constitute a serious criminal offence in the UK (p97).

[O]ne of the committee’s key concerns was that any such legislation must introduce an effective ‘economic espionage’ offence - something that the UK intelligence community suggested could be an important tool in the battle against China. At present, there are no criminal offences covering economic espionage that are not specifically linked to classified research or technology. A new offence might cover companies, research collaborations, joint ventures, seed funding, venture capital and access to academics and students covertly to obtain information data and intellectual property to secure commercial advantage against the UK (p98).

There should be ‘intelligence community’ oversight of decisions on foreign investment in the UK through the recently created ‘investment security unit’, it seems. So much, then, for ‘neoliberalism’ and ‘free market globalisation’. State interests require security apparat controls on foreign investment, on universities, and so on. The Orwellian nightmare approaches, as Oceania (US-UK) needs its own state security apparat with tentacles everywhere, in order to combat the looming threat of Eastasia (China).

Turn

The mention of David Cameron and Danny Alexander in the passage quoted above brings up another similarity between the ISC’s horror-fantasy about the Chinese threat and The riddle of the sands: the abrupt turn in UK policy which is involved. In 1894 Le Queux was writing about the danger of French invasion (backed by Russia), and the Brits were saved by German aid; for Childers nine years later the danger was German invasion (and Le Queux was to write in 1906 a German-invasion book, The invasion of 1910). Back to the halcyon days (in the light of what has followed) of the Con-Dem coalition of 2010-15, and the ‘China narrative’ was all about the opportunities for the UK in getting closer to China.8

Around 1900, what was involved in the radical turn of policy was the UK as a declining world hegemon (but still a world hegemon), trying to defend its interests by swapping allies in order to ‘contain’ rising Germany. The Entente policy of increasingly aggressive encirclement of Germany and Austria-Hungary, which followed, resulted at the end of the day in August 1914.

But, although 1914-18 led to the destruction of the tsarist regime, the Kaiser-Reich, the Austro-Hungarian empire and the Ottoman empire, 1919-1939 showed that it had failed to resolve the underlying problem of the global economy, which was the declining British empire as a vampire, sucking financial tribute out of the world. It took the destruction of the UK’s strategic global position, through the fall of France, the Low Countries, Denmark and Norway in 1940, to force the UK to agree in summer 1940 to hand over world leadership to the US. Even then, the UK tried to weasel out of the deal, with Keynes’s proposals at Bretton Woods in 1944, and by trying to act independently in alliance with France and Israel in Suez in 1956.

Since then, the UK has been very clearly a vassal state of the US. Not a colony or semi-colony: the king’s or feudal lord’s vassals were his military sub-tenants, not his serfs. Between 1956 and the 1990s the UK had quite significant military capability, though decreasingly practically independent of the US; it could be considered as a US attack-dog in the colonial world. In Afghanistan and Iraq the vaunted counter-insurgency capability of the British military proved to be a paper tiger, and Libya in 2011 only confirmed how limited UK military capability was. The UK has now become not a US attack-dog, but a US yap-dog: “Bark bark bark bark / Bark bark BARK BARK / Until you could hear them all over the park.”9 Its role is not to provide military services, but to be the loudest voice advocating the most aggressive policy (by comparison to which the US itself can try to appear ‘moderate’).

It is the US’s policy which has turned, with GW Bush’s 2000 characterisation of China as a “strategic competitor”, Obama’s 2011 “pivot to Asia”,10 followed by Trump’s open protectionism against China, and Biden’s continuation of that policy. The Cameron government was badly late grasping the turn of US policy towards China, and from 2015 distracted by Brexit. And now the ISC is playing catch‑up.

Communists should not be defenders of the Chinese regime any more than social democrats should have been defenders of the kaiser regime (which was also in many respects more ‘progressive’ than Britain in the late 19th to early 20th century).

Equally, however, we should not fall for the horror-stories produced as part of this report and/or in the media - as, for example, the Alliance for Workers’ Liberty’s Solidarity serves as an echo-chamber for the Biden administration’s China policy round the Uighurs, Taiwan and so on. These horror-stories are all, like The riddle of the sands, drum-beats of the coming war.

We cannot be advocates both, on the one hand, of the general liberation of humanity and, on the other hand, of the right of the USA or the UK to “security” from industrial and inter-imperialist competition and from “intellectual property theft”: ie, violation of monopolies.

-

isc.independent.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/ISC-China.pdf.↩︎

-

hansard.parliament.uk/Commons/2023-07-13/debates/23071347000027/IntelligenceAndSecurityCommitteeReportChina.↩︎

-

See, for example, M Rogin, ‘Kiss me deadly: communism, motherhood, and cold war movies’ Representations spring 1984.↩︎

-

‘Grand strategy and Ukraine’ Weekly Worker September 15 2022: weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/1410/grand-strategy-and-ukraine.↩︎

-

‘A bridge too far’ Weekly Worker December 18 2003 (weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/509/a-bridge-too-far); ‘Copyright or human need’ Weekly Worker December 14 2006 (weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/653/copyright-or-human-need).↩︎

-

Journal of Libertarian Studies vol 15 (2001).↩︎

-

Eg, www.theguardian.com/politics/2013/oct/14/george-osborne-china-visa; www.theguardian.com/business/2015/sep/20/osborne-china-visit-beijing-best-partner.↩︎

-

allpoetry.com/Of-The-Awefull-Battle-Of-The-Pekes-And-The-Pollicles.↩︎

-

www.brookings.edu/articles/the-american-pivot-to-asia (2011); foreignpolicy.com/2016/09/03/the-legacy-of-obamas-pivot-to-asia (2016).↩︎